It’s a story many of us heard countless times growing up, etched into Sunday school flannelgraphs and illustrated children's Bibles. Yet, watching the 1995 television film Joseph again, likely pulled from a slightly worn two-tape VHS set recorded off TNT back in the day, reveals a production that aimed for something grander, more psychologically nuanced than simple retelling. Part of Ted Turner's ambitious "The Bible Collection," this wasn't just another Sunday night movie; it was an event, an attempt to bring Old Testament scope and complexity to the small screen with surprising cinematic flair.

### Beyond the Technicolor Dreamcoat

What immediately strikes you about Joseph, helmed by Roger Young (a director adept at handling historical dramas like Moses from the same series), is its commitment to grounding the extraordinary tale in recognizable human emotion. While the narrative beats are familiar – the favored son, the jealous brothers, the pit, the rise to power in Egypt, the famine, the reunion – Lionel Chetwynd's script delves into the why. The simmering resentment of the brothers feels palpable, Jacob's damaging favouritism isn't glossed over, and Joseph's own youthful arrogance is laid bare before his trials forge him into a man of wisdom and profound forgiveness. This isn't merely pageantry; it's a family drama playing out on an epic stage.

### A Cast of Biblical Proportions

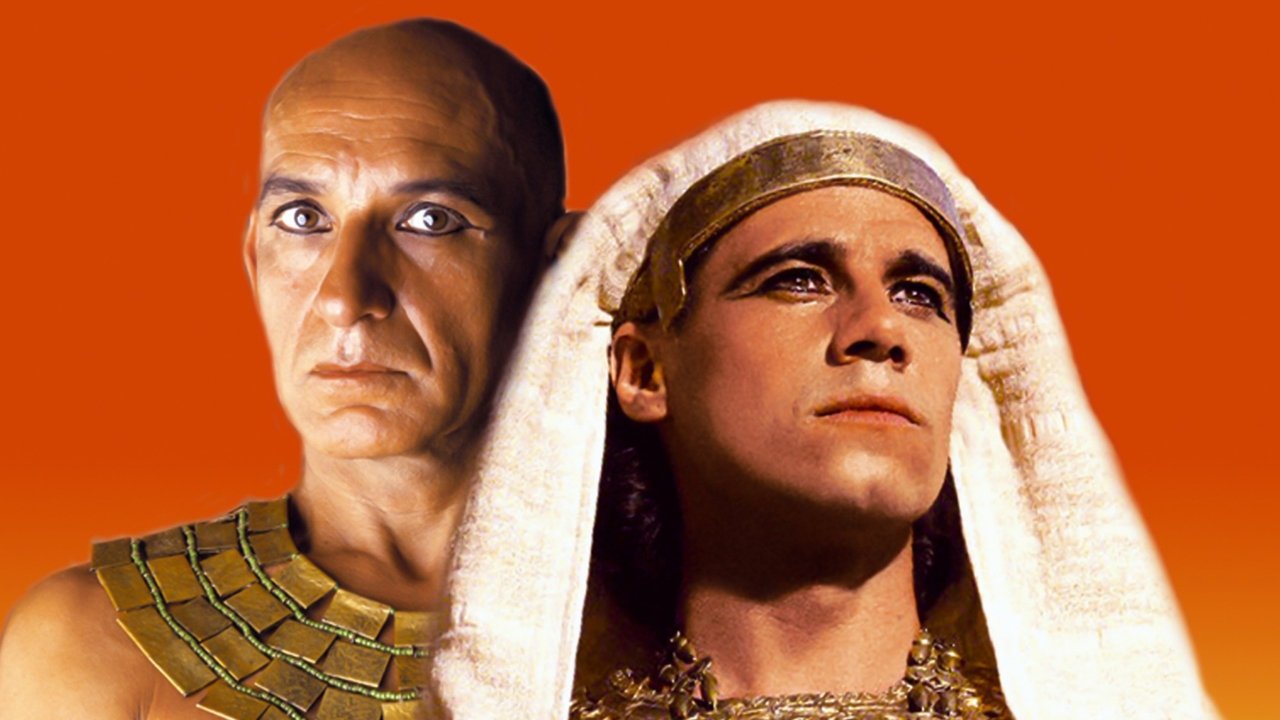

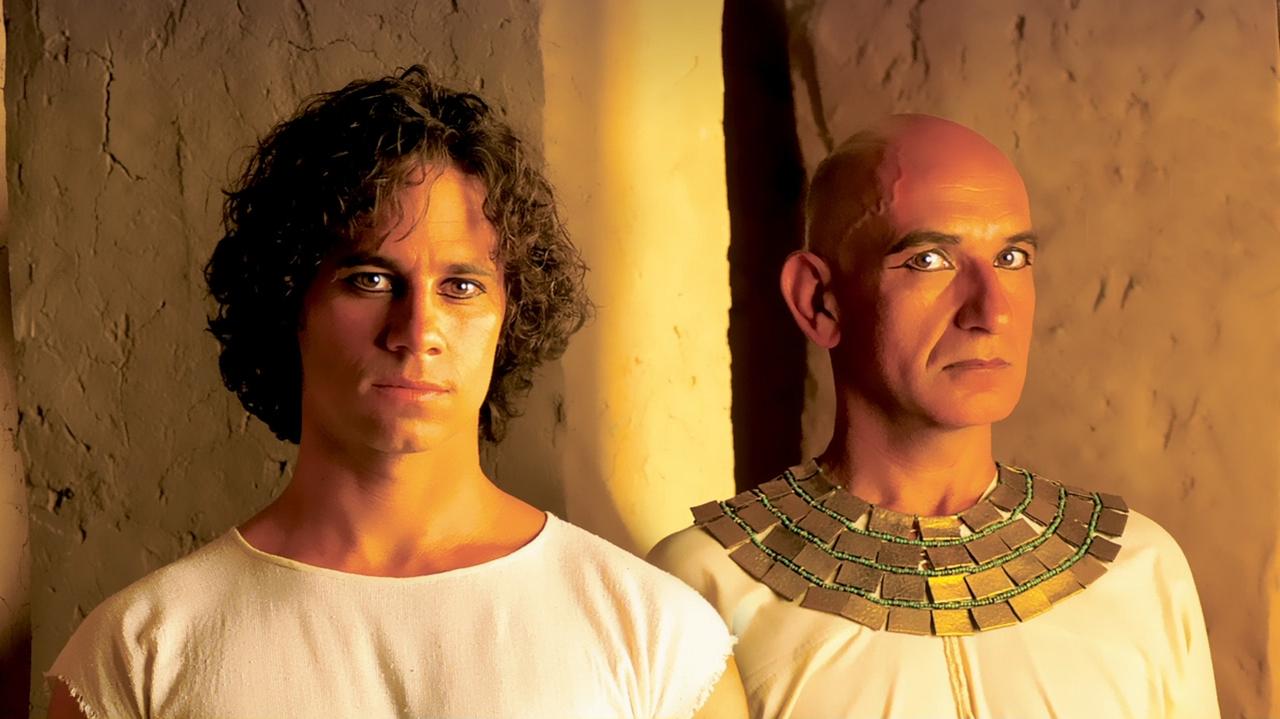

The casting is where Joseph truly elevates itself. Forget stunt casting; this feels deliberate, insightful. Ben Kingsley, fresh off his searing performance in Schindler's List (1993), brings an astonishing depth to Potiphar. He’s not just a functionary of Pharaoh; Kingsley portrays him as a man of quiet dignity, intelligence, and ultimately, deep hurt when faced with his wife's accusations against Joseph. His restraint speaks volumes, making Potiphar's internal conflict utterly compelling. It’s no surprise Kingsley snagged an Emmy for Outstanding Supporting Actor for this role – his scenes are masterclasses in understated power.

Then there's the legendary Martin Landau as Jacob. Landau, riding high after his Oscar win for Ed Wood (1994), embodies the patriarch's grief and flawed love with heartbreaking authenticity. The weight of his favouritism towards Joseph, and the consuming sorrow after his apparent death, anchors the first part of the film. You see the wisdom of age warring with the follies of a father's heart. Watching Landau and Kingsley, two titans of acting, inhabit these roles lends the production immense credibility.

As Joseph himself, Paul Mercurio (known best for Baz Luhrmann's vibrant Strictly Ballroom (1992)) faced the challenge of portraying a character across decades, from brash teenager to seasoned statesman. While perhaps not possessing the same gravitas as his elder co-stars initially, Mercurio effectively charts Joseph's evolution. He captures the early naivete and pride that invites disaster, and grows convincingly into the measured, forgiving leader who holds Egypt's fate, and his family's survival, in his hands. The chemistry, or calculated lack thereof, between him and his brothers feels tense and believable.

### Bringing Ancient Egypt to the Living Room

For a television production, the scale is impressive. Filmed largely on location in Ouarzazate, Morocco – a landscape familiar to viewers of epics like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and later Gladiator (2000) – the film achieves a sense of place and time that belies its budget constraints. Director Roger Young and cinematographer Raffaele Mertes make excellent use of the sweeping vistas and ancient-looking architecture (much of it purpose-built or adapted at the Atlas Film Studios). While it might not boast the sprawling sets of a DeMille epic, the production design feels authentic, immersing the viewer in Joseph's world, from the dusty pastures of Canaan to the opulent (if slightly restrained for TV) courts of Egypt. The visual storytelling, aided by Ennio Morricone's evocative score, effectively conveys both the intimacy of the family conflict and the grandeur of the Egyptian setting. This commitment to quality across the board clearly resonated, as Joseph deservedly won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Miniseries in 1995.

### More Than Just Sunday School: Themes That Endure

Beneath the familiar narrative lies a powerful exploration of themes that still resonate. How does one respond to profound betrayal, especially from family? What does true forgiveness look like, and is it always possible? Joseph tackles these questions head-on. Joseph's journey isn't just about surviving hardship; it's about learning to see a larger purpose, to trust in something beyond his immediate circumstances, and ultimately, to choose reconciliation over revenge. His famous line to his brothers, "You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good," isn't presented as a platitude, but as the hard-won conclusion of a life marked by suffering and redemption. Does this message feel overly earnest by today's cynical standards? Perhaps for some. But the sincerity of the performances and the conviction of the storytelling make it deeply affecting.

### Retro Fun Facts

- Part of a larger whole: Joseph was a key installment in TNT's ambitious "The Bible Collection," a series of films produced by the Italian company Lux Vide in collaboration with international partners, aiming to bring biblical stories to life with high production values for television audiences. Other entries included Abraham, Moses, and Samson and Delilah.

- Emmy Magnet: Beyond Kingsley's win and the Outstanding Miniseries award, the film racked up nominations for directing, writing, casting, and music composition, highlighting its overall quality.

- Location, Location, Location: The Moroccan locations provided not just authenticity but also production efficiencies, allowing the filmmakers to achieve a grander scale than might have been possible elsewhere on a television budget. The same region would later host parts of Game of Thrones.

- Mercurio's Shift: Casting Paul Mercurio, known primarily as a dancer and for the stylised Strictly Ballroom, was an interesting choice that paid off, showing his range beyond flamboyant romantic leads.

### Final Thoughts

Revisiting Joseph on VHS (or perhaps a slightly less fuzzy DVD release) is a reminder that television in the 90s could produce remarkably thoughtful and well-crafted historical dramas. It treats its source material with respect while exploring the complex human emotions at its core. The powerhouse performances, particularly from Ben Kingsley and Martin Landau, elevate it far beyond a simple Sunday school lesson. It’s a story about betrayal, resilience, and the transformative power of forgiveness, told with conviction and surprising cinematic depth for its time. It might lack the gritty realism or complex antiheroes popular today, but its earnest sincerity and emotional resonance still hold up.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: While occasionally showing its TV movie seams in terms of scope compared to theatrical epics, Joseph boasts exceptional lead performances (Kingsley, Landau), intelligent writing that delves into character psychology, strong direction, impressive production values for its medium, and a genuinely moving exploration of timeless themes. It successfully translates a foundational story into compelling human drama.

Lingering Question: Decades later, doesn't Joseph's struggle to forgive and find meaning in suffering still speak volumes about the challenges we face in navigating our own complex family dynamics and unexpected trials?