Okay, fellow travelers through time and tape, let’s dim the lights, ignore the tracking lines for a moment, and settle in for something truly unique from the mid-90s video store shelves. Forget the explosions and high-concept hooks for a second. Remember sometimes finding that unassuming box, maybe with a slightly austere cover, that promised something… different? That’s precisely the territory we’re entering with Louis Malle’s quiet marvel, Vanya on 42nd Street (1994). This isn't your typical night at the movies; it's more like being invited into a secret, sacred space where art is being made, raw and immediate.

### Ghosts in the Grandeur

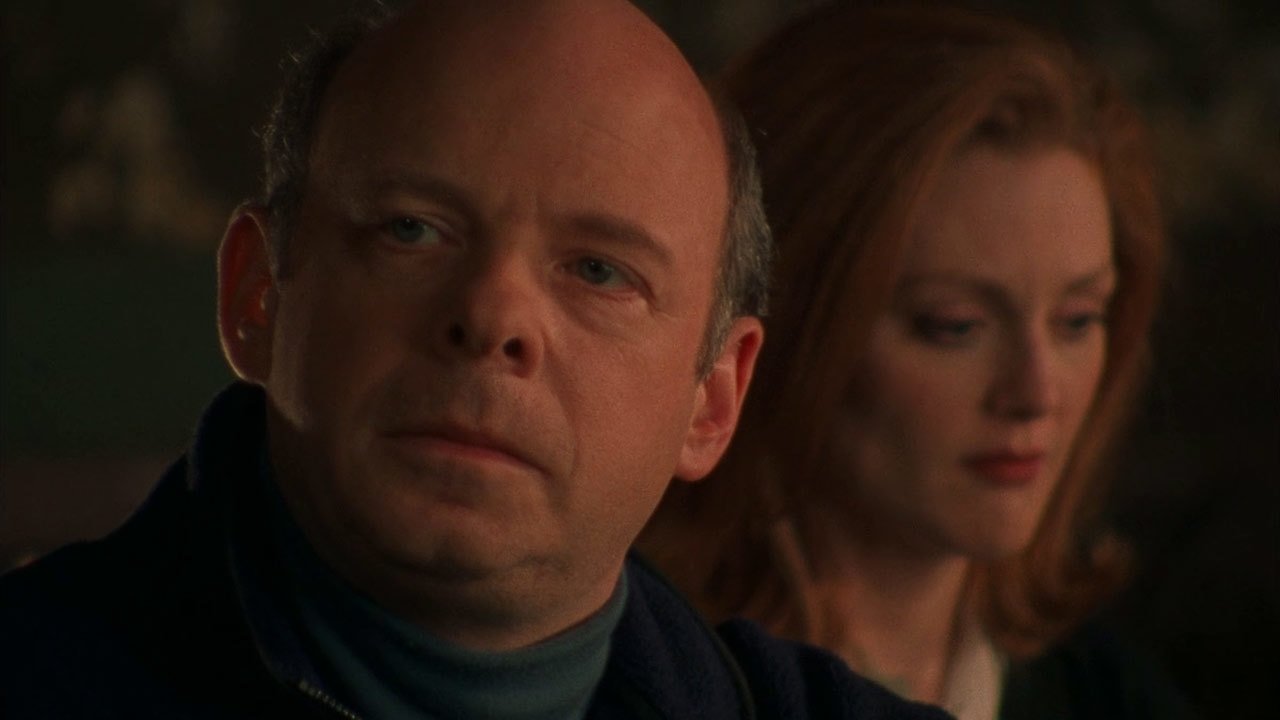

The film opens not with dramatic fanfare, but with the simple act of arrival. Actors, looking like ordinary New Yorkers, converge on a crumbling jewel box of a theatre – the then-derelict New Amsterdam on 42nd Street, years before its glittering Disney renaissance. There's Wallace Shawn, Julianne Moore, Larry Pine, Andre Gregory himself, greeting each other, grabbing coffee, shedding their street clothes for simple rehearsal attire. It feels documentary-like, casual. But then, almost imperceptibly, Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya begins. There’s no curtain rising, no announcement – just a shift in focus, a deepening of concentration, and suddenly, we are eavesdropping on the anguished heart of a 19th-century Russian estate, transplanted to the decaying grandeur of mid-90s Times Square.

This wasn't just a clever conceit; it was born from reality. Andre Gregory, who collaborates here again with Wallace Shawn after their iconic My Dinner with Andre (1981), had been workshopping this David Mamet adaptation of Vanya for years with this core group of actors. They performed it intermittently for small, invited audiences, often in similarly intimate, unconventional spaces. Louis Malle, capturing one of these final iterations, wisely chose not to open it up or make it conventionally "cinematic." Instead, he uses the very real decay of the New Amsterdam Theatre – the peeling paint, the ghostly emptiness – as a potent visual metaphor for the characters' own crumbling hopes and disillusionment. You can almost smell the dust and history, a far cry from a sterile soundstage.

### The Truth in Rehearsal

What unfolds is less a traditional film adaptation and more a captured performance, retaining the intimacy and intensity of theatre while using the camera's focus to draw us even closer. The plot, Chekhov's timeless exploration of unrequited love, environmental anxieties (Astrov’s passionate speeches about forest conservation feel startlingly relevant, don't they?), intellectual frustration, and the quiet desperation of lives unrealized, resonates deeply. But the how is what makes Vanya on 42nd Street extraordinary. We see the actors slip into their roles, but retain vestiges of themselves. Are we watching Wallace Shawn, or are we watching Vanya? Is that Julianne Moore, or the captivating, indolent Yelena? The lines blur beautifully.

The performances are uniformly stunning, stripped of theatrical artifice. Wallace Shawn embodies Vanya’s tragicomic despair with a vulnerability that’s almost painful to watch. His Vanya isn't a caricature of bitterness; he's a man whose heart has been slowly, inexorably crushed by circumstance and self-pity. Julianne Moore, even relatively early in her film career here, is magnetic as Yelena, the beautiful, younger wife of the pompous professor Serebryakov (George Gaynes, wonderfully cast against his usual comedic type from Police Academy fame). Moore conveys Yelena's allure, her boredom, and her own quiet suffering with subtle grace. And Larry Pine as Dr. Astrov, the object of affection for both Yelena and Sonya (Brooke Smith, heartbreakingly earnest), perfectly captures the weary idealism and hidden despair of a man devoted to both medicine and increasingly futile environmentalism.

### Malle's Final, Gentle Gaze

Louis Malle, in what would tragically be his final film (he passed away in 1995), directs with extraordinary restraint. His camera, wielded by Declan Quinn, observes rather than imposes. It catches the flicker of emotion in an actor's eyes, the shared glance across the room, the way the natural light falls through the grimy windows of the theatre. There are no flashy cuts or dramatic angles. The power comes from the text, the performances, and the palpable atmosphere of concentration and shared creation within that unique space. Hearing David Mamet's characteristically lean and rhythmic prose filter Chekhov's dialogue adds another fascinating layer – it feels both classic and immediate.

Finding this on VHS back in the day... well, it wouldn't have been the tape you rented for a rowdy Friday night with friends. It was more likely the kind of discovery you made when you were browsing alone, looking for something thoughtful, something that might stick with you. It demanded patience and attention, offering rewards far richer than simple escapism. It felt like stumbling upon a secret, a privilege to witness these actors breathing life into Chekhov in such an unadorned, powerful way. The film reportedly cost very little to make, a true passion project that sidestepped commercial concerns entirely, and that integrity shines through. It reminds us that sometimes, the most profound cinematic experiences don't require massive budgets or elaborate effects, just talented people, a great text, and a space filled with history and feeling.

### Lasting Echoes

Vanya on 42nd Street is a testament to the enduring power of Chekhov, the subtle art of performance, and the unique vision of Louis Malle. It captures a specific moment in time – both for the actors involved and for the historic theatre it occupies – creating a viewing experience that is melancholy, beautiful, and deeply human. It asks us to consider the lives we lead, the choices we make, and the hopes we cling to, even when they seem destined to fade like old paint in a forgotten theatre.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's sheer artistic integrity, the brilliance of the ensemble cast, and its success in creating a uniquely intimate and powerful cinematic experience from theatrical roots. It's a demanding watch, perhaps, but flawlessly executed and deeply rewarding.

Final Thought: It lingers not as a story told, but as an experience shared – a quiet hour or two spent in the company of ghosts, both fictional and real, contemplating the bittersweet beauty of it all.