There's a certain quiet hum that lingers after some films, a resonance that isn't loud but settles deep. Aki Kaurismäki's 1994 monochrome miniature, Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatjana (original Finnish title: Pidä huivista kiinni, Tatjana), leaves precisely that kind of echo. It’s the sort of film you might have stumbled upon back in the day, tucked away on the 'World Cinema' shelf of the video store, its stark cover art promising something… different. And different it certainly is. Watching it again now, it feels less like a movie and more like a captured moment of profound, awkward, and strangely beautiful human stillness.

Road Trip to Somewhere, or Nowhere?

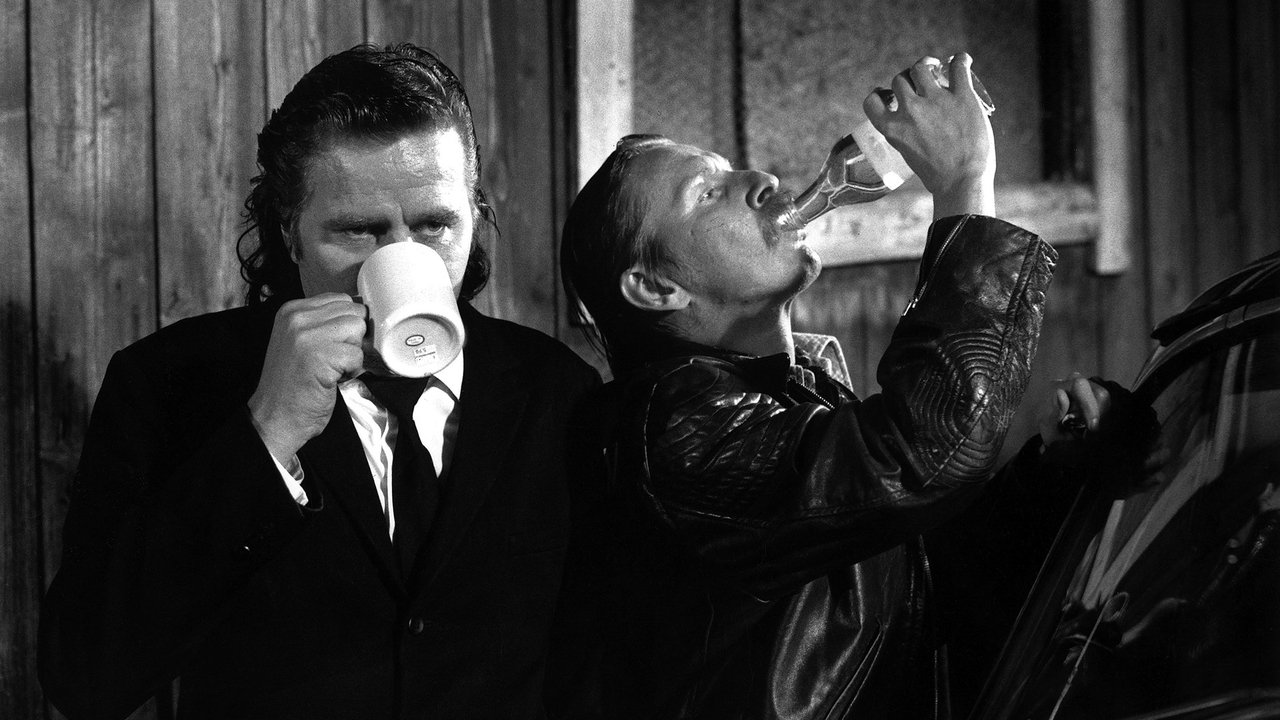

The premise is deceptively simple, almost threadbare. Valto (Matti Pellonpää), a stoic, coffee-addicted mechanic and mother's boy, embarks on an impromptu road trip with his equally taciturn, leather-jacketed friend Reino (Mato Valtonen), a hard-drinking rockabilly enthusiast. Their vintage Volga sedan becomes a vessel carrying them away from drab routine, fuelled by booze and cigarettes. Along the desolate Finnish roads, they encounter two women from the former Soviet Union – the reserved Tatjana (Kati Outinen) and the more outgoing Klavdia (Kirsi Tykkyläinen) – whose own journey has stalled. What follows isn't a conventional narrative arc, but rather a series of beautifully observed, minimalist encounters defined by longing glances, shared silences, and the hesitant possibility of connection across cultural and linguistic divides.

The Eloquence of Silence

Kaurismäki, a master craftsman of cinematic understatement who gave us gems like The Match Factory Girl (1990) and later The Man Without a Past (2002), paints here with a palette of grays, blacks, and whites, both literally and emotionally. The black-and-white cinematography by his regular collaborator Timo Salminen isn't just an aesthetic choice; it feels essential, stripping away distractions and focusing our attention on the faces, the landscapes, and the vast emptiness – both physical and emotional – that surrounds these characters. Dialogue is famously sparse; characters often communicate more through the tilt of a head, the lighting of a cigarette, or the shared experience of listening to a mournful tango or an upbeat rockabilly track playing on the car radio or a jukebox.

It’s a style that demands patience, asking the viewer to lean in and observe the subtle shifts beneath the impassive surfaces. What does Valto’s constant coffee consumption truly signify? Is Reino’s devotion to rock and roll a shield or an escape? The film doesn't offer easy answers, leaving us instead with poignant questions about loneliness and the difficulty of forging genuine connections, especially for men conditioned towards stoicism.

Portraits in Stillness

The performances are central to the film's unique charm. Matti Pellonpää, in one of his final screen appearances before his tragic death in 1995 at just 44, is utterly captivating as Valto. His face, often etched with a weariness that seems to go beyond the character, conveys volumes without uttering a word. There's a deep sadness in his eyes, a vulnerability hidden beneath the gruff exterior. His passing lends an extra layer of melancholy to watching the film today; it feels like capturing lightning in a bottle, preserving his unique screen presence. Kati Outinen, another Kaurismäki regular, matches him perfectly as Tatjana. Her performance is a masterclass in micro-expressions, suggesting a hidden wellspring of feeling beneath her reserved demeanour. The hesitant, unspoken chemistry between Valto and Tatjana forms the fragile heart of the film. And Mato Valtonen, best known perhaps as a member of the Finnish novelty band Leningrad Cowboys (who Kaurismäki famously directed in Leningrad Cowboys Go America (1989)), brings a different, slightly more volatile energy as Reino, his rockabilly obsession providing much of the film's soundtrack and deadpan humour.

Finnish Soul, Universal Longing

While deeply rooted in a specific Finnish sensibility – the quiet endurance, the love of coffee and vodka, the affinity for melancholic music – the film's core themes are universal. It explores the awkward dance of human interaction, the fear of vulnerability, and those fleeting moments where connection seems possible, even if ultimately elusive. Running at barely an hour, it’s a concise, almost poetic statement. Kaurismäki reportedly kept the production lean, as was his custom, focusing resources on capturing the right atmosphere and performances rather than elaborate set pieces. This economic filmmaking style perfectly mirrors the film’s minimalist aesthetic. There’s a charming anecdote that Kaurismäki often gives his actors the script pages only for the day's shoot, enhancing the sense of spontaneous, lived-in moments, even within his carefully composed frames.

Does anything truly happen in Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatjana? In conventional plot terms, perhaps not much. But emotionally, it covers vast territory. It’s a film that stays with you, not because of dramatic twists, but because of its honesty, its quiet humanity, and its unforgettable mood. It reminds us of those unexpected discoveries in the video store aisles – films that didn't shout but whispered, offering a glimpse into different worlds and different ways of being.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: This rating reflects the film's mastery of its unique minimalist style, the superb, understated performances (especially Pellonpää's poignant turn), and its ability to evoke deep feeling through silence and imagery. It's a perfectly crafted piece of Kaurismäki's distinctive cinematic world, achieving precisely what it sets out to do. It might not be for everyone due to its pacing and deliberate lack of action, but for those attuned to its wavelength, it’s a deeply rewarding, funny, and melancholic gem.

Final Thought: It’s a reminder that sometimes the most profound journeys are the internal ones, even if they only take you as far as the next cup of coffee or the end of a rockabilly song on a lonely highway.