Sometimes, a film doesn't shout; it whispers. It draws you in not with explosions or frantic chases, but with the patient observation of light falling on a leaf, the rhythmic chop of vegetables, the quiet presence of someone watching the world unfold. Tran Anh Hung's debut feature, The Scent of Green Papaya (1993, original title: Mùi đu đủ xanh), is precisely such a film – a cinematic meditation that felt like a rare, precious find on the video store shelves back in the day, nestled perhaps incongruously between action flicks and broad comedies. It demanded a different kind of attention, a slowing down that felt almost radical then, and perhaps even more so now.

A World Within Walls

The film transports us to Saigon, first in 1951, where we meet Mui (Man San Lu), a young girl arriving from the countryside to work as a servant for a struggling middle-class family. She enters a household shadowed by unspoken grief – a missing father, a perpetually sorrowful mistress ( Thi Loc Truong), and the lingering memory of a deceased daughter whom Mui resembles. Through Mui's observant eyes, we witness the daily rituals, the hidden tensions, and the small beauties of this enclosed world. Ten years later, the narrative shifts, and an adult Mui (Tran Nu Yên-Khê, the director's wife and muse) moves to work for Khuyen, a handsome, modern pianist she has long admired from afar.

What's astonishing, and a piece of trivia that still boggles the mind, is that this vibrant, humid slice of Vietnamese life was meticulously recreated entirely on a soundstage just outside Paris. Knowing this adds another layer to appreciating the film's artistry. The lush vegetation, the rain-slicked courtyards, the interplay of light and shadow – all constructed, yet feeling utterly authentic. It speaks volumes about Tran Anh Hung's precise vision and the skill of his production team in conjuring not just a place, but a palpable atmosphere.

The Eloquence of Silence

The Scent of Green Papaya is a film that trusts its audience to watch and listen intently. Dialogue is sparse; meaning is conveyed through gesture, expression, and the careful framing of shots. We learn about the family's dynamics not through exposition, but by observing the Mistress's melancholic gaze, the grandmother's quiet wisdom, or the boisterous cruelty of the younger sons. Young Man San Lu as Mui is captivating, her face a canvas of curiosity and quiet resilience. She finds fascination in the smallest things – ants carrying crumbs, frogs croaking in the rain, the milky sap oozing from a cut green papaya. This focus on the minute details elevates the mundane to something poetic.

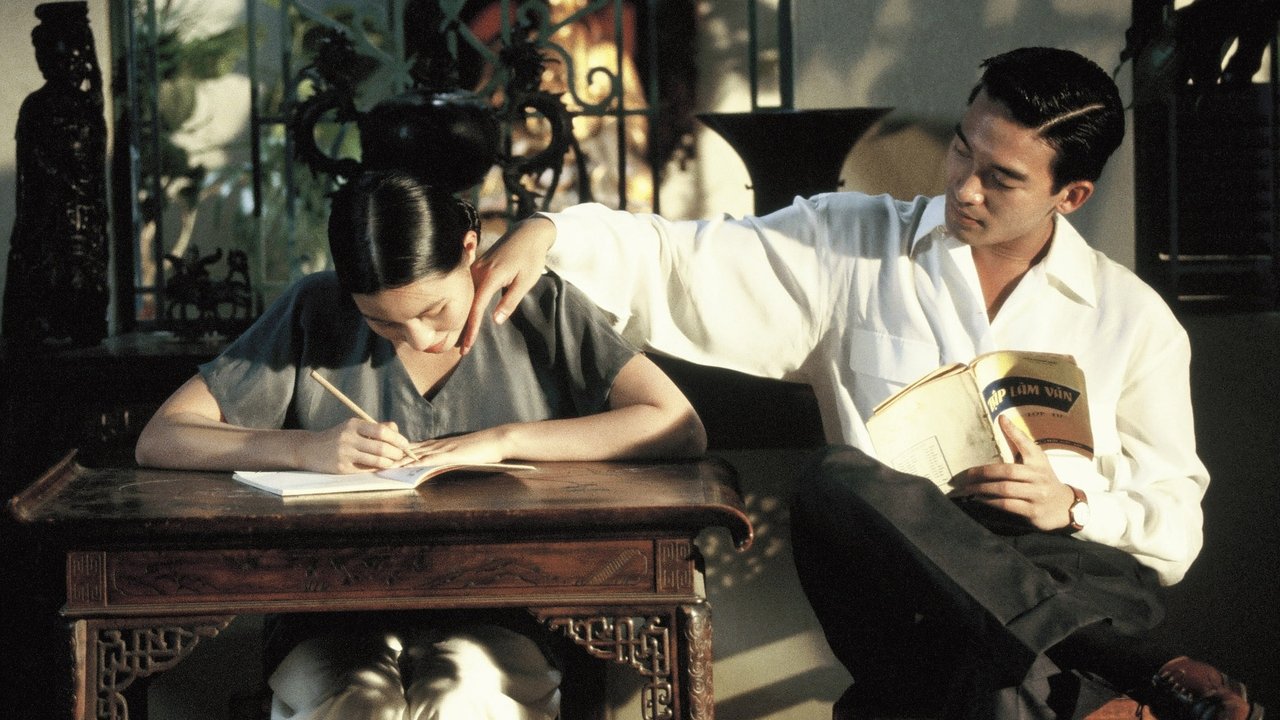

When Tran Nu Yên-Khê takes over as the adult Mui, the performance retains that watchful quality but adds layers of burgeoning self-awareness and gentle sensuality. Her interactions with Khuyen are charged with unspoken feeling, culminating in moments of breathtaking tenderness communicated largely without words. It’s a performance of exquisite subtlety, proving that powerful emotions don't always need grand pronouncements. Doesn't it make you think about how much can be communicated just through a look, or the way someone moves through a room?

Sensory Immersion

More than plot, this film is about sensation. Hung focuses intensely on textures – the smooth skin of the papaya, the rough fabric of clothes, the cool surface of tiles. The sound design is equally crucial, amplifying the natural world: the incessant chirp of crickets, the drumming of monsoon rain, the sizzle of food cooking. The preparation of meals becomes a central ritual, filmed with an almost loving attention to detail. Watching Mui carefully slice the green papaya, its scent seemingly wafting from the screen, is one of the film's most iconic and defining images. It's a symbol of sustenance, of simple beauty, and perhaps of Mui's own unripe potential slowly blossoming.

This sensory focus made it a unique experience on VHS. On a smaller CRT screen, you perhaps leaned in closer, focusing on the details, letting the film's deliberate pace wash over you. It was the antithesis of the quick-cut editing dominating much of 90s cinema, offering instead a space for contemplation. I remember finding it at a local rental place known for having a decent foreign film section – it felt like discovering a hidden jewel.

A Quiet Triumph

While not a blockbuster, The Scent of Green Papaya made significant waves. It won the prestigious Caméra d'Or (for best first feature film) at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival and snagged an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film – a remarkable achievement for a debut. It heralded the arrival of Tran Anh Hung as a major voice in world cinema and contributed to the growing international appreciation for Asian filmmaking in the 90s.

The film isn't entirely without its critics; some find the pace too slow, the narrative too slight. And yes, the second half, focusing on Mui and Khuyen, perhaps feels a touch more conventional than the almost ethnographic observation of the first. Yet, its power lies precisely in its quietude, its painterly visuals, and its profound empathy for its central character. It finds extraordinary beauty and depth within the confines of domestic life, exploring themes of observation, memory, loss, and awakening desire with uncommon grace.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's stunning artistry, its immersive atmosphere, and the quiet power of its performances. It's a masterclass in visual storytelling and sensory filmmaking. While its deliberate pace might not suit every viewer, its unique beauty and emotional resonance are undeniable. The Scent of Green Papaya lingers long after the credits roll, like a haunting melody or, indeed, a delicate, unforgettable scent. It remains a testament to the power of cinema to transport us, not through noise, but through stillness and grace.