It starts with a feeling, doesn't it? That sudden, almost vertiginous rush you get watching Richard Gere as Mr. Jones, seemingly dancing on the edge of the world during one of his manic highs. There's an undeniable charisma there, magnetic and alarming all at once. Watching Mr. Jones (1993) again after all these years, pulling that familiar tape from its slightly worn sleeve, that feeling returns – a mix of fascination and unease that sits right at the heart of this ambitious, if sometimes tangled, romantic drama. It forces you to ask: how close can you get to someone's brilliant, chaotic fire without getting burned yourself?

The High Wire Act of Being Jones

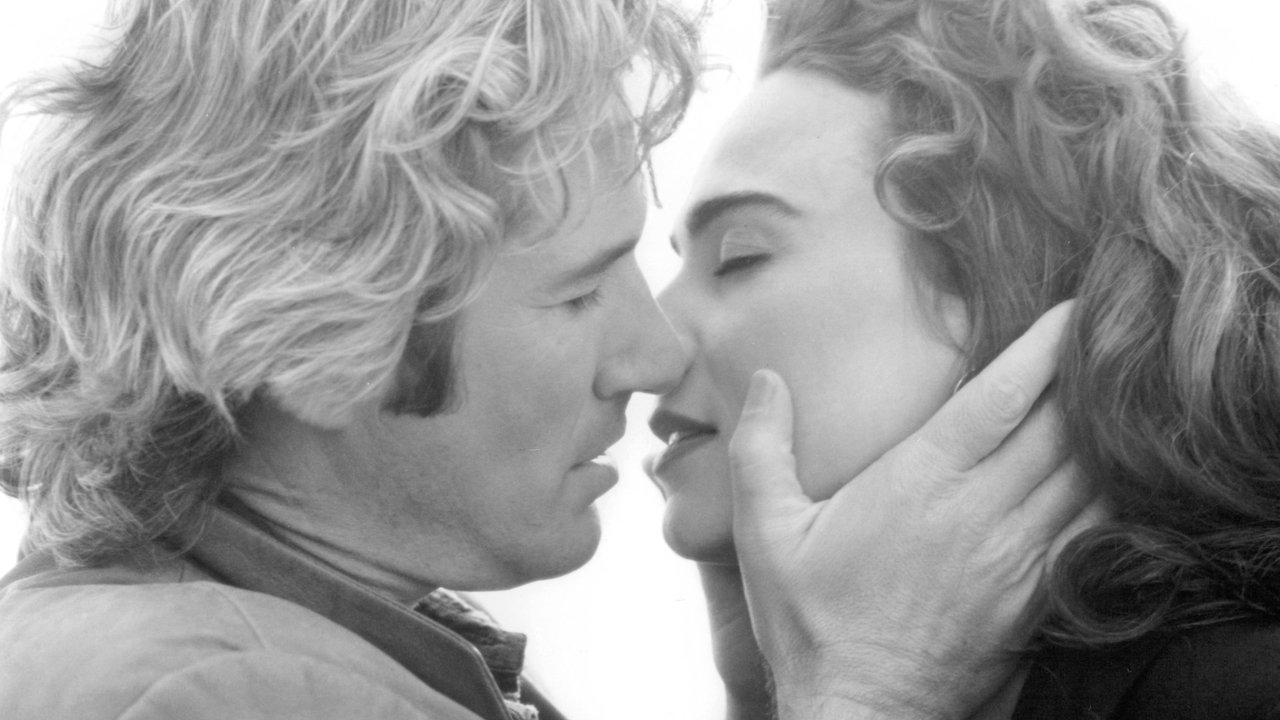

The premise introduces us to Jones, a man whose irresistible charm and bursts of incredible energy are the outward signs of bipolar disorder. He lands, inevitably, under psychiatric care, where Dr. Libbie Bowen (Lena Olin) finds herself increasingly drawn to his complex personality. It's a setup rife with potential, exploring the allure of someone living life at an intensity most of us only glimpse, while simultaneously grappling with the devastating consequences of his illness. Gere, stepping away from the smoother operators he often played (**think Pretty Woman or American Gigolo), throws himself into the role with a kinetic energy that’s hard to look away from. He captures the intoxicating speed of the highs – the rapid-fire ideas, the boundless optimism, the feeling of being plugged directly into the universe. Crucially, he also conveys the crushing weight of the subsequent lows, the withdrawal and despair that follow the inevitable crash. It's a performance that feels committed, even if the script occasionally struggles to contain the sheer force of the character.

Navigating the Ethical Tightrope

Opposite Gere, Lena Olin delivers a performance layered with intelligence and vulnerability. As Dr. Bowen, she represents the audience's way into Jones's world, initially observing him with professional detachment, then fascination, and ultimately, a deeply complicated affection. Olin excels at portraying Libbie’s internal struggle – the ethical conflict between her duties as a doctor and her burgeoning feelings for a patient. Their chemistry is palpable, charged with an attraction that feels both compelling and dangerous. Does the film fully explore the problematic nature of this relationship? Perhaps not as deeply as a modern lens might demand, but Olin makes Libbie’s dilemma feel real and deeply human. Supporting her is the ever-reliable Anne Bancroft as Dr. Catherine Holland, offering a grounding presence and a voice of professional caution, though her screen time feels somewhat limited.

Figgis's Atmospheric Lens

Director Mike Figgis, who would later give us the stark intensity of Leaving Las Vegas (1995), brings a certain visual style to Mr. Jones, even if it feels slightly more conventional than his later work. There's a sensitivity in how he frames Jones's experiences, attempting to convey the subjective reality of his mania and depression without resorting to cheap visual tricks. The score by the legendary Maurice Jarre (known for epics like Lawrence of Arabia) adds another layer, often reflecting the soaring highs and melancholic undertows of Jones's state of mind. The film aims for a certain naturalism, grounding the heightened emotions in believable settings. Interestingly, Figgis wasn't the original director; Jon Amiel (who directed the excellent Copycat) started the picture but left due to creative differences, leaving Figgis to step in and reshape it. You can sometimes feel the seams of different visions, perhaps contributing to the film's slightly uneven tone.

Behind the Mania: Retro Insights

Getting a film like Mr. Jones made in the early 90s wasn't straightforward. Portrayals of mental illness were often caricatured or overly simplified. Gere reportedly spent considerable time researching bipolar disorder, meeting with individuals and doctors to understand the nuances, striving for authenticity within the bounds of a Hollywood narrative. The script itself, co-written by Eric Roth (who would later pen Forrest Gump and The Insider) and Michael Cristofer, attempts to balance the romantic elements with a serious look at the condition. The ethical quandary of the central romance was reportedly a point of discussion even then. Made on a decent budget for the time (around $30 million), its box office performance was modest (grossing just over $18 million domestically), perhaps reflecting audience uncertainty about its blend of heavy themes and star-driven romance. Initial reviews were mixed, with some praising the performances while questioning the romanticization of the doctor-patient relationship. It remains a film that sparks debate – a testament, perhaps, to its willingness to tackle difficult subject matter, even imperfectly.

Does Love Conquer All?

Ultimately, Mr. Jones walks a fine line. It wants to be a moving romance about connection and acceptance, but it's also grappling with the harsh realities of a serious mental illness and the ethical complexities of therapeutic relationships. Does it succeed on all fronts? Maybe not entirely. The romance, while fueled by strong chemistry, sometimes feels like it smooths over the sharper, more difficult edges of Jones's condition and Libbie's professional compromise. Yet, there's an undeniable sincerity to the effort. It treats Jones not as a monster or a saint, but as a human being struggling with forces beyond his control, capable of great love and creativity alongside immense pain. What lingers after the credits roll isn't just the memory of Gere's whirlwind energy, but the quiet question of empathy – how much can we truly understand another's inner world, and what responsibilities come with that understanding?

Rating: 6/10

This score reflects the film's genuine strengths – primarily the committed performances from Richard Gere and Lena Olin and its earnest attempt to portray bipolar disorder with some sensitivity for its time. However, it’s docked points for the somewhat uneven tone and the way the central romance occasionally simplifies or skirts around the profound ethical and personal challenges inherent in the situation. It tries to be both a serious drama and a star-driven romance, and doesn't always reconcile the two seamlessly.

Mr. Jones might not be a perfect film, but it’s a fascinating snapshot from an era when Hollywood was cautiously beginning to explore mental health narratives with more nuance. It stays with you, less perhaps for its plot resolution and more for the questions it raises about the dazzling, dangerous beauty found on the edges of human experience. It’s a film that, like its title character, is complex, flawed, and ultimately quite memorable.