Okay, let's dim the lights, maybe pour a glass of something thoughtful, and slide this tape into the VCR. Remember the feeling? The clunk, the whir… and then, the screen flickers to life. Today, we're revisiting Alfonso Cuarón's lush, perhaps audacious, 1998 take on Great Expectations. Forget dusty Victorian England; this adaptation plunges us headfirst into the humid haze of the 90s Florida Gulf Coast and the sleek, sharp edges of the New York art scene. It's a film that immediately announces its intentions through its visuals – a bold move, and one that defines the entire experience.

A Dickens Dreamscape in Green

The most immediate and lasting impression of this Great Expectations isn't necessarily the plot, which takes considerable liberties with Charles Dickens' sprawling novel, but its overwhelming atmosphere. Alfonso Cuarón, years before his Oscar triumphs with Gravity and Roma, was already demonstrating an incredible eye, working alongside his frequent collaborator, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki. They bathe the film in a palette dominated by greens – the decaying verdure of Ms. Dinsmoor's Floridian estate, Paradiso Perduto; the subtle shades in clothing; the very light filtering through windows. It creates a mood that's simultaneously seductive and melancholic, a visual correlative for the longing and thwarted desire at the heart of the story. It's less a faithful adaptation and more a translation of themes into a specific, heightened aesthetic reality. Screenwriter Mitch Glazer wasn't aiming for a literal retelling; he was chasing a feeling, a modern myth spun from classic threads.

Faces of Longing and Loss

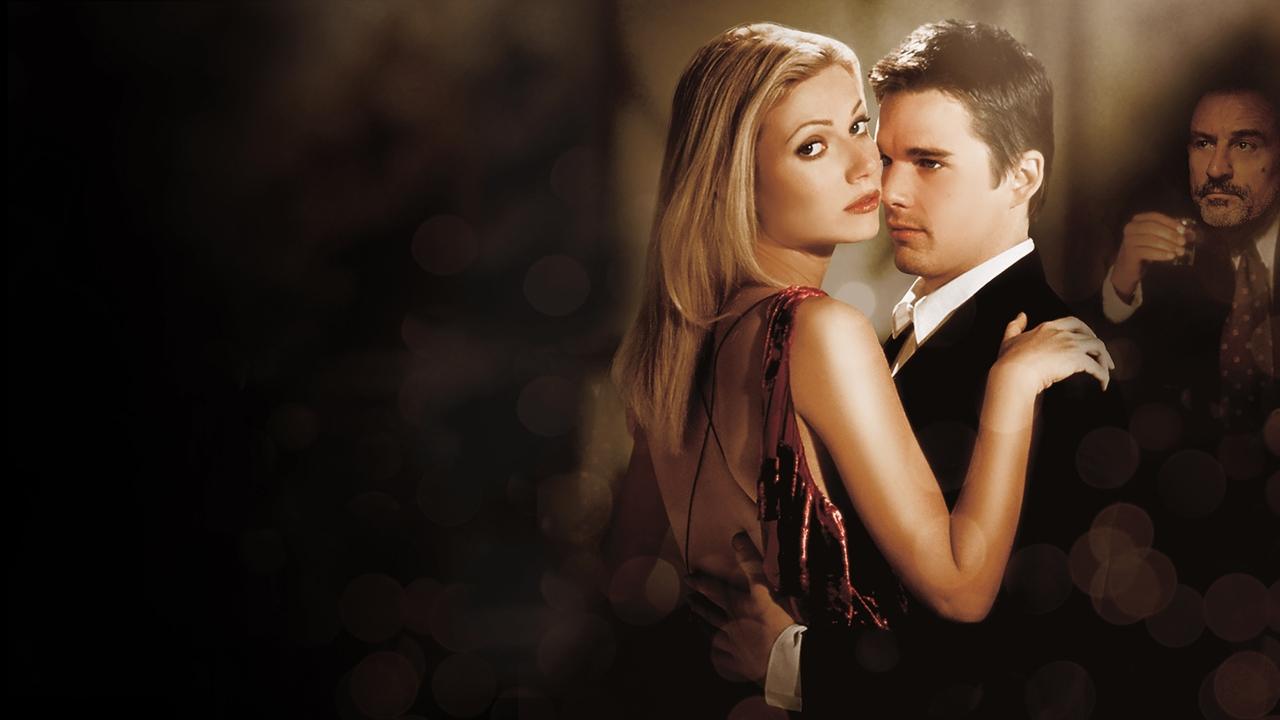

Anchoring this visual feast are the performances, particularly from the young leads. Ethan Hawke, embodying the renamed Pip, Finn Bell, brings that earnest, slightly wounded intensity he perfected in the 90s (think Reality Bites). You feel Finn's raw ambition, his confusion, and most palpably, his aching, almost lifelong obsession with Estella. And Gwyneth Paltrow, as the elusive object of his affection, Estella, is pitch-perfect 90s cool wrapped around a core of carefully guarded vulnerability. Their chemistry is undeniable, fraught with the tension of misunderstanding and missed connections. It’s a portrayal of youthful infatuation that feels authentic to the era – intense, a little bit dramatic, and utterly consuming.

But it's often the supporting players who steal scenes. Anne Bancroft as Ms. Dinsmoor (this version's Miss Havisham) is magnificent. Forget dusty wedding dresses; Bancroft’s Dinsmoor is a creature of faded glamour, cigarette smoke, and psychological decay, swaying to old records in her crumbling mansion (the stunning Ca' d'Zan in Sarasota, Florida, served as the exterior). She delivers lines like "Chicka-boom" with a theatrical weariness that’s both terrifying and strangely pitiable. And then there's Robert De Niro in a relatively brief but crucial role as Arthur Lustig (the Magwitch figure). It’s a testament to the project's allure, perhaps, that De Niro took the part; reportedly, he filmed his scenes quickly, almost as a favor, yet his presence lends a necessary gravity to Finn’s mysterious patronage. We also get a warm, grounding turn from Chris Cooper as Finn's Uncle Joe.

Art Imitating Life (and Vice Versa)

One of the adaptation's cleverest moves is reframing Pip's journey through the lens of the art world. Finn isn't just trying to become a gentleman; he's an aspiring artist. This allows the film to visually represent his transformation and internal state. And here’s a fantastic piece of trivia: the striking, expressive paintings and sketches attributed to Finn in the film? They were actually created by the renowned contemporary Italian artist Francesco Clemente. This wasn't just set dressing; Clemente’s work becomes integral to the narrative, reflecting Finn's emotional landscape and his tumultuous relationship with Estella. It adds a layer of meta-commentary on creation, inspiration, and the often-painful sources of artistic expression.

This artistic sensibility extends to the film's soundtrack, a veritable time capsule of late-90s alternative cool. Tracks from artists like Pulp, Scott Weiland, Iggy Pop, Chris Cornell, and the hypnotic "Life in Mono" by Mono (which became synonymous with the film's trailers) don't just accompany the scenes; they deepen the mood, adding layers of yearning, sophistication, and simmering angst. It was one of those soundtracks many of us bought separately, letting the film's atmosphere linger long after the credits rolled. Reportedly selling over 600,000 copies in the US alone, it was a significant hit in its own right.

A Flawed Beauty?

Was it a perfect film? Perhaps not. Some critics at the time (and viewers since) found the narrative streamlining a bit too severe, leaving the plot feeling occasionally thin compared to the rich tapestry of the source material. The updated ending, apparently influenced by test screenings, also drew some debate compared to Dickens' more ambiguous conclusion. Made on a budget of around $26 million, it pulled in about $55 million worldwide – respectable, but not a blockbuster, suggesting it found its audience but didn't quite capture the mainstream zeitgeist.

Yet, watching it again now, decades removed from its initial release, its strengths feel more pronounced. The sheer confidence of Cuarón's visual storytelling is breathtaking. The performances, especially Bancroft's, linger. And the mood – that specific blend of 90s style, timeless longing, and Floridian gothic – remains potent. It’s a film that commits fully to its aesthetic vision, sometimes at the expense of narrative depth, but the result is undeniably captivating. I remember renting this tape, drawn in by the cast and the trailer's hypnotic visuals, and being swept away by its sheer style.

---

VHS Heaven Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's stunning visual artistry, incredible atmosphere, memorable performances (especially Bancroft), and killer soundtrack, which firmly plant it as a unique 90s artifact. Points are slightly deducted for the narrative streamlining that occasionally leaves the plot feeling secondary to the style, and an ending that might feel less impactful than the source material. However, its ambition and distinctive mood make it far more memorable than many more conventional adaptations.

Final Thought: A gorgeous, moody time capsule that traded Dickensian scope for 90s aesthetic intensity. It might not be the Great Expectations purists were looking for, but as a visual poem about obsessive love and the allure of transformation, it casts a spell that's hard to shake. What remains is the color green, the echo of a haunting song, and the feeling of being lost in someone else's beautiful, tragic dream.