There's a certain kind of swagger that defined aspects of the early 90s, a particular brand of unapologetic ambition teetering on the edge of parody. Few films captured this quite like Bigas Luna's 1993 Spanish drama Huevos de oro, known to many of us clutching our rental copies simply as Golden Balls. Forget subtlety; this film announces its intentions with the same confidence as its protagonist, a force of nature embodied by a young, electrifying Javier Bardem. Watching it again now, decades removed from its initial release, feels like unearthing a time capsule filled not just with questionable fashion, but with potent, almost operatic commentary on machismo and the dizzying highs and lows of unchecked desire.

A Monument to Masculinity

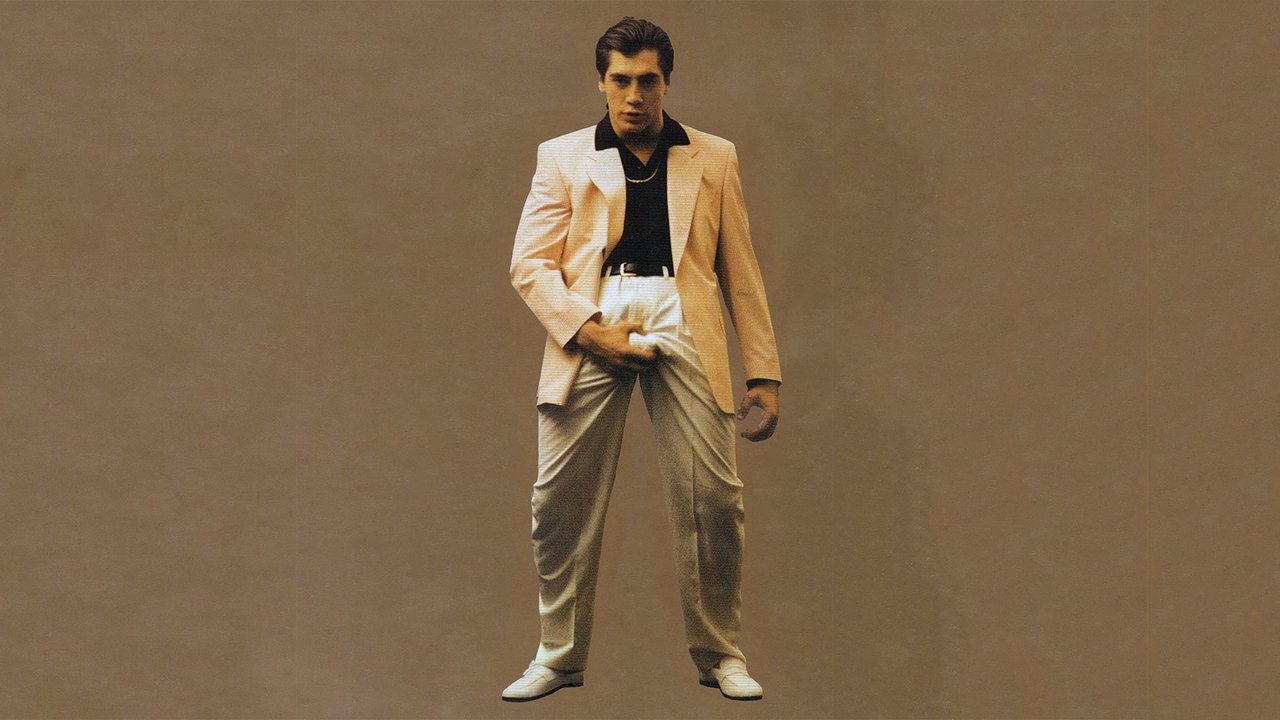

The film introduces us to Benito González (Javier Bardem) right after a breakup leaves him vowing to build a massive skyscraper and possess twin golden ornaments – literal huevos de oro – to adorn it. It's a mission statement dripping with Freudian symbolism and bare-chested ambition. Bardem, hot off his breakout in Luna’s Jamón Jamón (1992), is mesmerizing. He reportedly gained significant weight for the role, adding a physical bulk that underscores Benito's earthiness and voracious appetites – for success, for women, for more. This isn't the nuanced, world-weary Bardem we know from later roles like No Country for Old Men (2007); this is raw charisma, a primal energy barely contained. He struts, he sweats, he consumes, embodying a specific archetype of Spanish masculinity pushed to its absolute extreme. You can almost feel the concrete dust and cologne radiating off the screen.

Bigas Luna's Provocative Palette

Director Bigas Luna, who co-wrote the screenplay with Cuca Canals, had a unique cinematic language, one deeply rooted in Spanish culture yet universally resonant in its exploration of primal urges. Golden Balls forms the middle part of his "Iberian Trilogy," nestled between Jamón Jamón and The Tit and the Moon (1994), and shares their obsessions: food, sex, national identity, and the often-absurd collision of tradition and modernity. Luna wasn't afraid to be vulgar, excessive, or visually arresting. The film is soaked in the garish sunlight and architectural ambition of Benidorm, a Spanish coastal resort town whose skyline becomes a character in itself – a testament to the construction boom and speculative frenzy gripping Spain at the time. Luna uses this backdrop brilliantly, contrasting Benito's crude ambition with the almost surreal landscape of holiday high-rises. It's a visual feast, sometimes beautiful, sometimes deliberately crass, perfectly mirroring the protagonist's journey.

Ambition, Excess, and the Women Caught in the Orbit

Benito's rise is meteoric, fueled by marrying Marta (Maria de Medeiros, recognizable to many from Pulp Fiction (1994)), the daughter of a wealthy banker. De Medeiros brings a fragile intelligence to Marta, a woman initially drawn to Benito's power but increasingly aware of its destructive potential. Yet, Benito's gaze soon wanders to Claudia (Maribel Verdú, another Luna regular who would later star in Y Tu Mamá También (2001) and Pan's Labyrinth (2006)), embodying a more overt sensuality. The dynamic between these characters explores the complex, often transactional nature of relationships within Benito's empire of ego. It's a world where affection is tangled with finance, and loyalty is as precarious as a half-finished building. Does his relentless drive reveal something fundamental about the pursuit of power, or is it merely the caricature of a man blinded by his own reflection? The film doesn't offer easy answers. Keep an eye out, too, for a brief but memorable appearance by a very young Benicio del Toro, radiating a quiet menace that foreshadows his future stardom, playing a rival who represents the lurking threat beneath Benito's success.

Retro Fun Facts: Building Benito's World

Luna’s dedication to his vision was palpable. Bardem’s commitment, beyond the physical transformation, involved fully inhabiting Benito’s unrefined energy – a stark contrast to the actor's thoughtful off-screen persona. The choice of Benidorm wasn't accidental; its unique, almost futuristic (for the time) cluster of skyscrapers provided the perfect visual metaphor for Benito's aspirations and the burgeoning, sometimes reckless development transforming parts of Spain. There’s a fascinating anecdote that Luna was partly inspired by the ostentatious displays of wealth he witnessed during Spain’s economic boom years. The film’s title itself, Huevos de oro, is a bold, provocative statement – slang for "guts" or "balls" but also literally referring to the golden spheres Benito wants atop his tower, a symbol so obvious it becomes almost profound in its audacity. Initial reactions were often strong, reflecting the film’s confrontational style – it wasn’t aiming for gentle approval.

The Unraveling and the Echo

Naturally, such unchecked ambition rarely ends well. Benito's empire, built on bluster and borrowed time (and money), begins to crumble. The descent is as dramatic and visually potent as the rise, marked by betrayal, desperation, and the stark realization that the foundations were always weak. What lingers after the credits roll isn't just the striking imagery or Bardem's powerhouse performance, but the unsettling feeling that Benito, despite his monstrous flaws, is a recognizable figure. Haven't we all encountered versions of this character, driven by ego and a desperate need for validation, leaving chaos in their wake?

Finding Golden Balls on VHS back in the day often meant venturing into the 'World Cinema' section, a treasure trove of films that felt riskier, more adult, and visually distinct from Hollywood fare. It was provocative, sometimes uncomfortable, but undeniably alive. Revisiting it now, it feels less like a mere artifact and more like a potent, darkly funny satire whose themes of greed, fragile masculinity, and the seductive danger of ambition still resonate.

Rating: 8/10

Golden Balls earns its 8 for its sheer audacity, Javier Bardem's unforgettable early performance, and Bigas Luna's distinctive, uncompromising vision. It’s visually rich, thematically provocative, and captures a specific moment in time with operatic flair. While its excesses might not be for everyone, and the symbolism is anything but subtle, its power as a character study and a biting social commentary remains potent. It’s a film that grabs you, shakes you, and leaves you thinking about the precariousness of building monuments to oneself.

It stands as a bold, brassy reminder from the VHS shelves that sometimes, the most interesting stories are the ones told with unapologetic fervor, even if they chronicle a spectacular fall from grace.