It sometimes feels like the early 90s video store shelves offered two distinct flavours of foreign film: the intensely serious arthouse epic, demanding quiet contemplation, or something altogether lighter, promising charm and perhaps a different kind of escape. Fernando Trueba’s Belle Époque (1992) firmly belongs to the latter, yet beneath its sun-drenched, comedic, and often delightfully sensual surface, it asks questions about freedom, choice, and the nature of happiness that linger long after the charmingly simple credits roll. It arrived, perhaps unexpectedly for many North American viewers browsing the racks, adorned with the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, a testament to its captivating power.

### An Unexpected Paradise

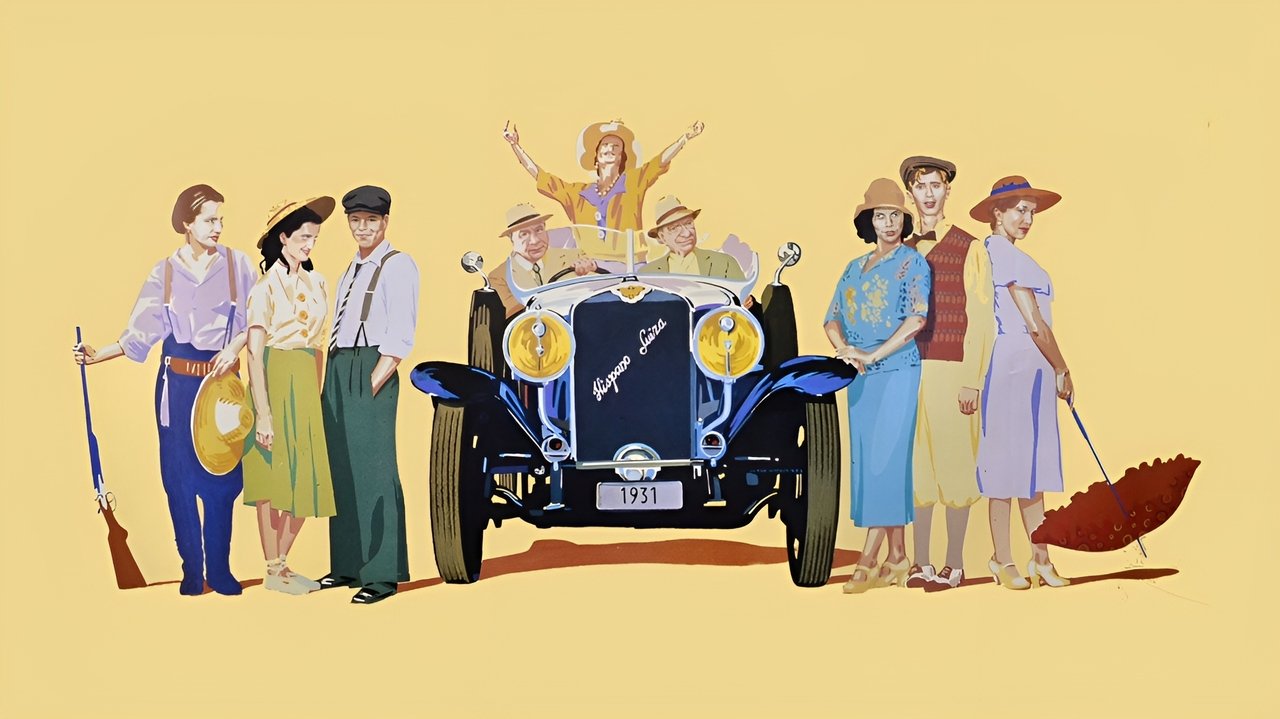

The setup is deceptively simple, almost fable-like. We're in Spain, 1931. The monarchy has fallen, the Second Republic is dawning, but whispers of future conflict are already in the air. Young army deserter Fernando (Jorge Sanz) finds himself wandering, lost and disillusioned, until he stumbles upon the remote country estate of Manolo (Fernando Fernán Gómez), a wise, witty, and staunchly atheistic painter. Manolo offers sanctuary, philosophical musings, and, most significantly, the company of his four stunningly beautiful, fiercely independent daughters, who arrive home just as Fernando considers leaving. What follows is less a conventional plot and more an episodic exploration of Fernando's entanglements with each sister – the recently widowed Clara (Miriam Díaz Aroca), the fiery Violeta (Ariadna Gil) who initially mistakes Fernando for a woman, the scheming Rocío (Maribel Verdú), and the youngest, seemingly innocent Luz (Penélope Cruz in a star-making early role).

### A Celebration of Life and Love

What unfolds isn't high drama, but a warm, often funny, and unabashedly sensual celebration of life's pleasures. Trueba, working from a script he co-wrote with Spanish cinema giants Rafael Azcona (Plácido, The Executioner) and José Luis García Sánchez, directs with a wonderfully light touch. The film luxuriates in its idyllic setting, captured beautifully by cinematographer José Luis Alcaine. Think rolling hills bathed in golden light, leisurely meals under shady trees, and nights filled with conversation and possibility. It evokes the spirit of Renoir's countryside paintings, a conscious influence Trueba acknowledged, mixed with the sophisticated romantic entanglements reminiscent of Ernst Lubitsch's comedies. It's a film that believes in the pursuit of happiness, even – or perhaps especially – when the world outside is teetering on the brink.

The ensemble cast is key to the film's infectious charm. Jorge Sanz, as the somewhat passive Fernando, is our relatable entry point – swept along by events, often bewildered, but open to the experiences washing over him. He embodies a certain youthful uncertainty that feels entirely authentic. The veteran Fernando Fernán Gómez is magnificent as Manolo, the freethinking patriarch who observes the romantic chaos with amused detachment and dispenses worldly wisdom. His presence grounds the film, giving its hedonism a philosophical anchor. And then there are the sisters, each distinct and captivating. Ariadna Gil's Violeta provides some of the film's funniest moments, while Maribel Verdú brings a sly energy to Rocío. It was, however, Penélope Cruz as the seemingly pure Luz who truly captured international attention. Even here, early in her career, she possesses that undeniable screen presence, hinting at the depths beneath the character's naive surface. The chemistry between all the actors feels natural and lived-in, creating a believable, if heightened, family dynamic.

### More Than Just Sunshine

But Belle Époque isn't merely frothy escapism. The historical context, while never intrusive, provides a poignant counterpoint to the personal dramas unfolding. Manolo's quiet anarchism and the daughters' liberated attitudes represent the freedoms ushered in by the Republic, freedoms that history tells us would soon be brutally suppressed by the Spanish Civil War. This knowledge lends a bittersweet quality to the film's joyful abandon. It’s a snapshot of a fleeting moment – a "beautiful era" – before the storm. This subtle political layer, woven seamlessly into the fabric of the narrative by the masterful Rafael Azcona, elevates the film beyond simple romantic comedy. It asks us, perhaps, what truly matters when faced with uncertain times: political ideals, or the simple, profound connections we forge with others?

Finding this on a VHS tape, possibly nestled between Hollywood blockbusters, felt like discovering a hidden gem back in the day. It was different – unapologetically European in its pacing and sensibility, frank about sexuality without being exploitative, and intelligent in its humour. Winning the Oscar over highly favoured films like Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine surprised many, but watching it again, its appeal is clear. It offered a specific kind of warmth and humanism, a belief in pleasure and connection that felt both timeless and refreshingly grown-up. It wasn't trying to be profound in a heavy-handed way; its depth emerged organically from its characters and their embrace of life.

Rating: 8/10

Belle Époque earns this score for its sheer, unadulterated charm, bolstered by fantastic ensemble performances, witty writing, and beautiful direction. It expertly balances its light, sensual tone with a subtle awareness of its historical moment. While its episodic structure might feel slight to some, its cumulative effect is deeply winning. It's a film that leaves you smiling, bathed in the warmth of its Spanish sun and pondering the simple, radical act of choosing happiness. What better definition of a beautiful era, however brief it might be?