It begins not with a story, but with a feeling. A series of fragments – light falling through a window, the sound of rain on cobblestones, the disembodied voices from a nearby cinema screen drifting into a quiet living room. Terence Davies' The Long Day Closes (1992) isn't a film you watch so much as one you inhabit, a deeply personal immersion into the sensory world of a lonely boy finding solace and shape in the sights and sounds around him. It feels less like a narrative and more like leafing through a half-remembered photo album, where emotions linger more vividly than events.

Watching it again, decades after first encountering it perhaps tucked away in the 'World Cinema' or 'Drama' section of the video store, its power remains undiminished. It’s a film that rewards patience, asking you to slow down and simply observe alongside its young protagonist, Bud.

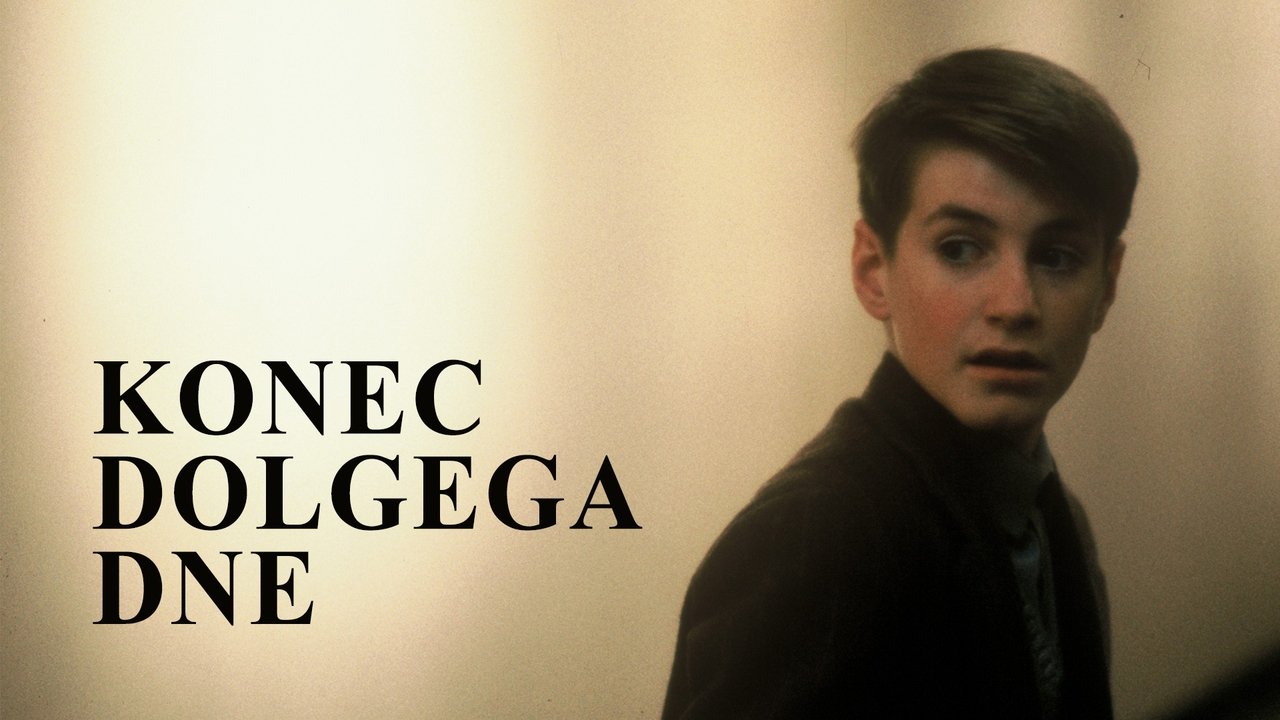

A Child's Gaze, Perfectly Captured

At the heart of the film is eleven-year-old Bud (a remarkably intuitive performance by Leigh McCormack), Davies' own childhood surrogate navigating life in working-class Liverpool in the mid-1950s. Bud is often alone, frequently positioned near windows or doorways, an observer rather than an active participant. McCormack conveys volumes with just a look – curiosity, fear, quiet joy, the dawning awareness of complex adult emotions he doesn't fully grasp. There’s an almost unnerving stillness to him at times, reflecting a child's intense internal processing of the world. We see the warmth of his Catholic family – particularly his loving mother, played with gentle strength by Marjorie Yates – but also the casual cruelty of school bullies and the oppressive weight of religious guilt. What does it feel like to be small, sensitive, and slightly apart from the world? Davies, through McCormack, remembers with aching clarity.

Memory Woven from Sound and Image

Davies, who also penned the script, crafts a cinematic language built on association rather than linear progression. Scenes dissolve into one another, linked by a recurring motif, a piece of music, or a shared emotional tone. This isn't the Liverpool of gritty social realism; it's Liverpool filtered through memory, nostalgia, and the heightened sensitivity of childhood. The meticulous production design recreates the era, but the feel comes from Michael Coulter's cinematography – the rich, often shadowed interiors, the specific quality of light – and Davies’ masterful use of sound.

The soundtrack is extraordinary, a tapestry woven from snippets of film dialogue (Doris Day, The Magnificent Ambersons), popular songs of the day drifting from the wireless, and hymns. Music isn't just background noise here; it's emotional architecture. It provides comfort, escape, and sometimes an ironic counterpoint to Bud's experiences. Davies understands implicitly how songs and movie moments embed themselves in our memories, becoming intertwined with specific times and feelings. I recall discovering Davies' earlier autobiographical work, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), on VHS and being similarly struck by this potent use of music – it felt like unlocking someone else's intensely personal memory box.

Whispers from Behind the Curtain

Knowing The Long Day Closes is deeply autobiographical adds another layer. Davies has spoken about drawing directly from his own experiences, his own family, his burgeoning awareness of his homosexuality (hinted at subtly in Bud's fascination with male physique magazines and moments of intense male bonding), and his complex relationship with Catholicism. This isn't just fiction; it's a confession, an exorcism, a love letter to a vanished time and the people who populated it. The film reportedly cost around £1.6 million to make – a modest sum even then for such a carefully constructed period piece – and premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, signalling its art-house intentions rather than aiming for blockbuster status. It wasn't a film designed for easy consumption; it was, and remains, an intensely personal vision. You can almost feel Davies standing just off-camera, guiding McCormack through the echoes of his own past. It’s said Davies often works from these potent memories rather than a rigid script, letting the feeling dictate the flow – a process perfectly reflected in the finished film.

The Lingering Resonance

What stays with you after The Long Day Closes ends? It’s the quiet moments: Bud watching his siblings dance, the shared warmth around the fireplace, the solitary comfort found in the darkness of the cinema. It captures the specific melancholy of childhood – that sense of moments slipping away even as you experience them. It's a film about finding refuge – in family, in music, in the flickering images on a screen – when the outside world feels overwhelming or confusing. Doesn't that search for sanctuary resonate, regardless of the era we grew up in?

It lacks a conventional plot, which might frustrate some viewers accustomed to more straightforward narratives. But its power lies elsewhere – in its atmosphere, its emotional honesty, and its unique portrayal of subjective memory. It’s a film that washes over you, leaving behind a residue of profound tenderness and a quiet ache for the irretrievable past.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's exceptional artistry, its emotional depth, and the unique, unwavering vision of its director. Terence Davies crafts a deeply moving and formally brilliant exploration of childhood memory that uses sound and image with extraordinary sensitivity. Leigh McCormack's performance is central to its success, capturing the quiet intensity of observation. While its contemplative pace and non-linear structure demand viewer engagement, the reward is a profoundly affecting cinematic experience that resonates long after the screen fades to black.

It remains a beautiful, melancholic poem committed to film – a quiet treasure from the 90s that reminds us how powerfully cinema can capture the internal landscape of a life.