### That Summer Stillness, That Basement Secret

There's a certain kind of quiet that settles over a house when the adults are gone. Not the liberating quiet of temporary freedom, but something heavier, thicker. In Andrew Birkin's The Cement Garden (1993), that quietness is palpable, almost suffocating. It clings to the peeling wallpaper and the overgrown garden of a dilapidated suburban London home, a silence born not of peace, but of a secret buried deep in the cellar. This isn't your typical coming-of-age story; it's a descent into a strange, self-contained world where childhood's end collides violently with grief and unspoken desires. I remember encountering this film on VHS, perhaps tucked away in the 'Drama' section but radiating an unsettling aura that hinted at something far more complex, and it’s a film that settles under your skin and stays there.

### A House Without Rules

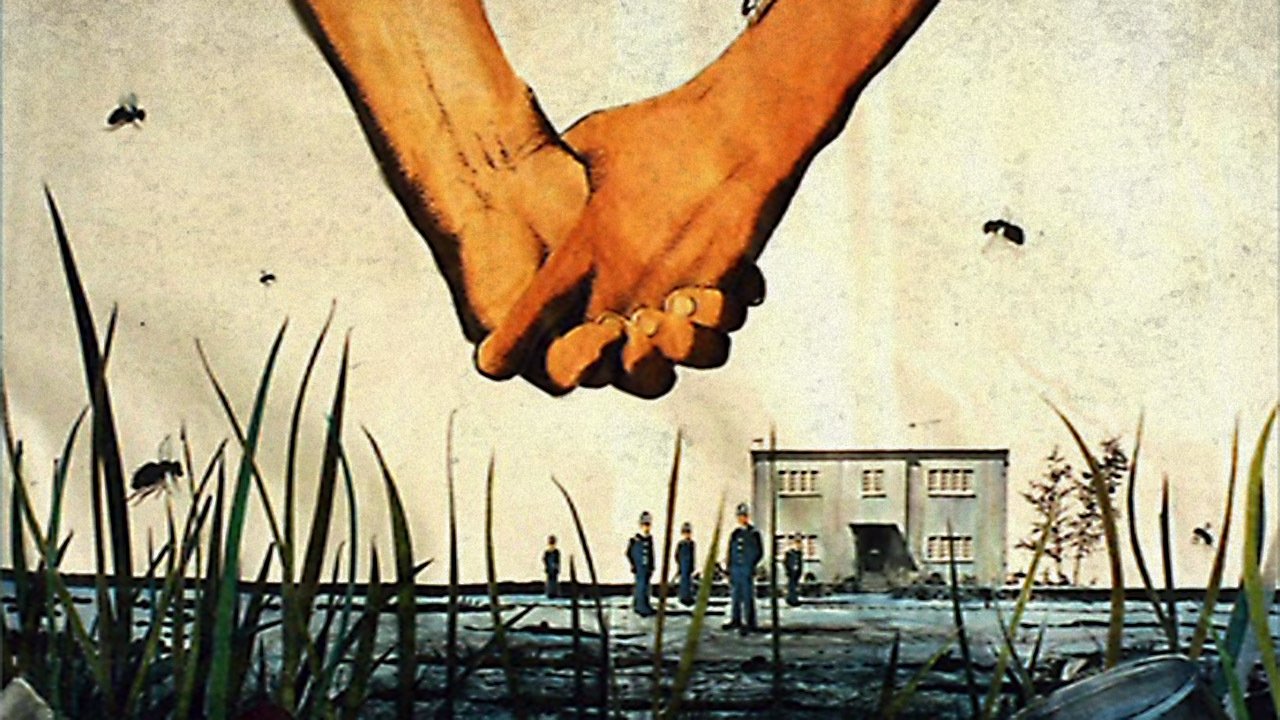

Adapted from Ian McEwan's stark 1978 novel (McEwan also co-wrote the screenplay), the premise is brutally simple yet profoundly disturbing. After their father's sudden death and their mother's subsequent decline and demise from illness, four siblings – teenager Julie (Charlotte Gainsbourg), narrator Jack (Andrew Robertson), the introspective Sue (Alice Coulthard), and young Tom (Ned Birkin) – make a chilling pact. To avoid being separated and sent to foster care, they encase their mother's body in cement in the basement. What follows isn't a thriller about discovery, but a haunting observation of isolation. The house becomes their island, detached from the outside world, bathed in the oppressive heat of an endless summer. Director Andrew Birkin, who interestingly is Charlotte Gainsbourg's uncle and whose own son Ned plays the youngest child, uses this real-life family connection, perhaps unintentionally, to heighten the sense of claustrophobia and intimacy within the frame. You feel the closeness, the shared history, even as it curdles into something unsettling.

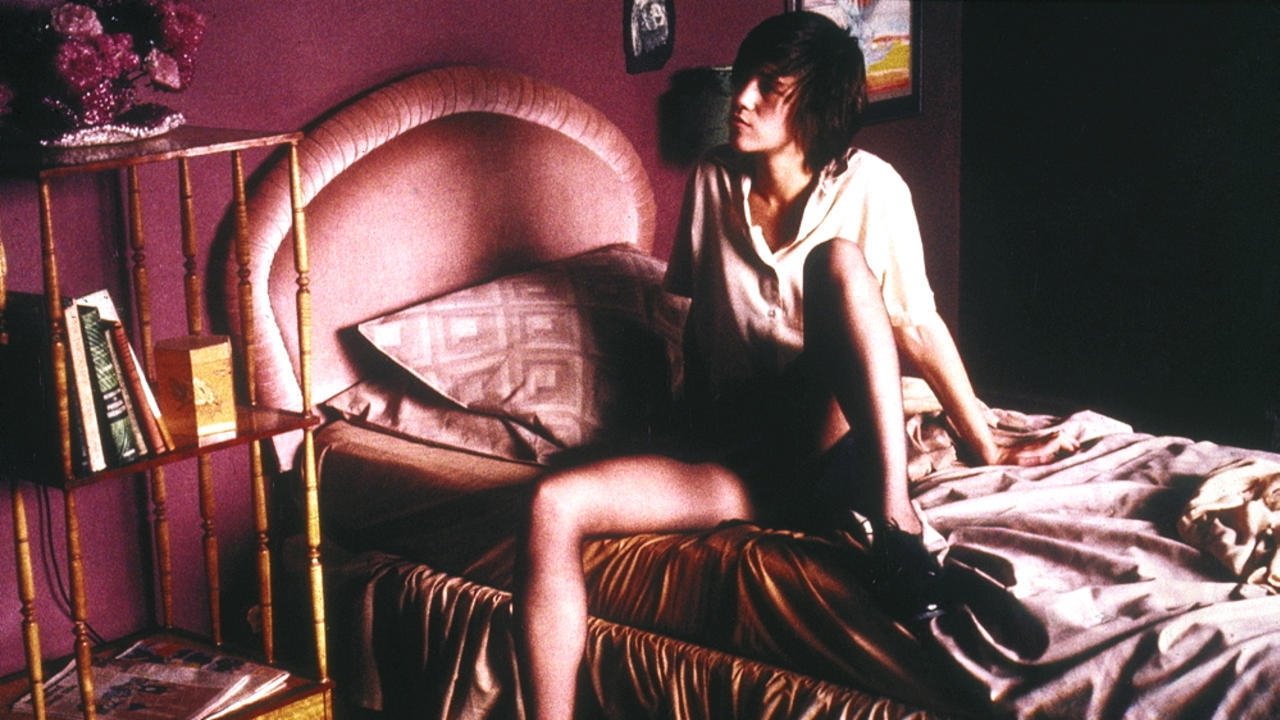

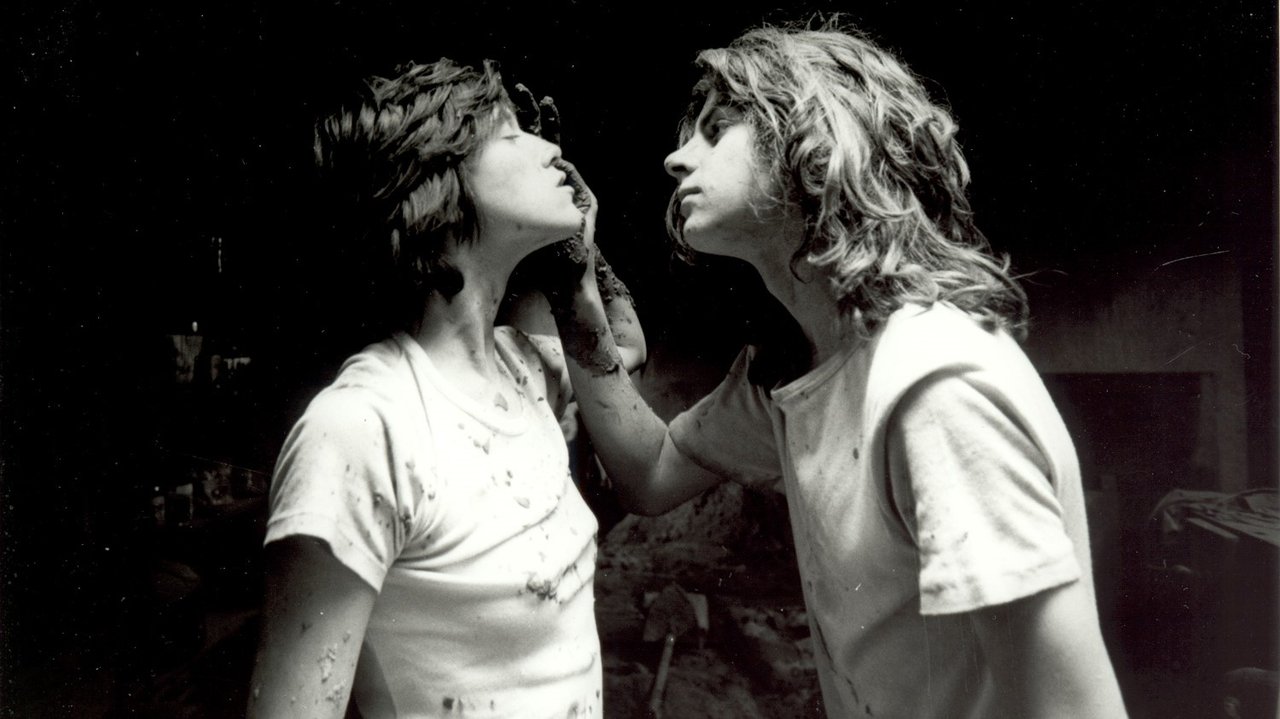

### Performances That Breathe Unease

The power of The Cement Garden rests heavily on its young cast, who navigate extraordinarily difficult material with unnerving authenticity. Andrew Robertson as Jack provides the film's anchor, his narration laced with a mixture of adolescent awkwardness, burgeoning sexuality, and a dawning awareness of the darkness settling over them. He watches, participates, and judges, often simultaneously. But it’s Charlotte Gainsbourg, already a compelling presence following films like L'Effrontée (1985), who truly mesmerizes. As Julie, she embodies a premature, weary maturity. She steps into the maternal void, yet her actions ripple with a troubling ambiguity, blurring the lines between care, control, and something far more taboo. Her performance is magnetic – still, watchful, and hinting at depths the film wisely leaves somewhat unexplored. Alice Coulthard’s Sue, diligently recording events in her diary, offers glimpses of a fading innocence, while Ned Birkin’s Tom, exploring gender identity by dressing in his sisters' clothes, represents a different kind of boundary-pushing within their sealed world. These aren't 'acting' performances in the showy sense; they feel lived-in, capturing the listlessness and confusion of grief mixed with a strange, unsettling freedom.

### Atmosphere Over Action

Birkin crafts a film that prioritizes atmosphere above all else. The visual language is one of decay – the crumbling house, the rampant weeds reclaiming the garden, the dust motes dancing in the hazy sunlight pouring through grimy windows. Filming largely took place in a single house in East London during a particularly hot summer, and you can almost feel the sweat, the lethargy, the stifling quality of the air trapped within those walls. This tangible sense of place is crucial. The outside world barely intrudes; neighbours are distant figures, societal rules seem irrelevant. The siblings create their own micro-society, governed by impulses and needs rather than convention. It’s a deliberate choice that mirrors McEwan’s focused, intense prose, refusing easy sensationalism in favour of psychological exploration. The film courted controversy, naturally, given its handling of incestuous undertones, but Birkin approaches it with a detached observational eye rather than for shock value, making it all the more disquieting. It’s no surprise the film garnered attention, winning Birkin the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin International Film Festival that year.

### Lingering Questions in the Dust

What stays with you long after the VCR whirred to a stop isn't necessarily the shock of the premise, but the pervasive sense of unease and the questions it raises about family, grief, and the fragile boundaries of societal norms. How thin is the veneer of civilization when stripped of adult supervision and confronted with profound loss? Are the siblings' actions monstrous, or a tragic, distorted attempt to preserve their fragile unit against an indifferent world? The Cement Garden offers no easy answers. It simply presents this sealed, overheated world and allows the viewer to draw their own conclusions. It’s a challenging piece, certainly not for everyone, and a stark contrast to the often brighter, more boisterous fare typical of early 90s cinema found on those rental shelves.

---

Rating: 8/10

Justification: The Cement Garden earns its high rating through its masterful creation of atmosphere, its brave and unsettling exploration of taboo themes, and the remarkably nuanced performances from its young cast, particularly Charlotte Gainsbourg. While its deliberate pacing and disturbing subject matter make it a challenging watch, Andrew Birkin's direction is confident and controlled, delivering a film that is both faithful to Ian McEwan's source material and powerfully cinematic in its own right. It's a potent piece of 90s independent filmmaking that prioritizes psychological depth over narrative convention, leaving a lasting, uncomfortable impression.

Final Thought: It's a film that reminds you how silence can be louder than screams, and how sometimes the most disturbing gardens are the ones we cultivate within ourselves.