It arrives with a title like a slap, doesn't it? Whore. No euphemisms, no softening the edges. Just the blunt, stark reality director Ken Russell intended to confront us with back in 1991. Forget the fairytale gloss of Pretty Woman (1990) that had charmed audiences the year before; this film, based on David Hines' monologue play Bondage, aimed for the jugular, stripping away any romanticism clinging to the world's oldest profession. Seeing that stark VHS box on the rental shelf, often relegated to a less prominent spot, felt like a dare. Did you have the stomach for what was inside?

A Street-Level Confession

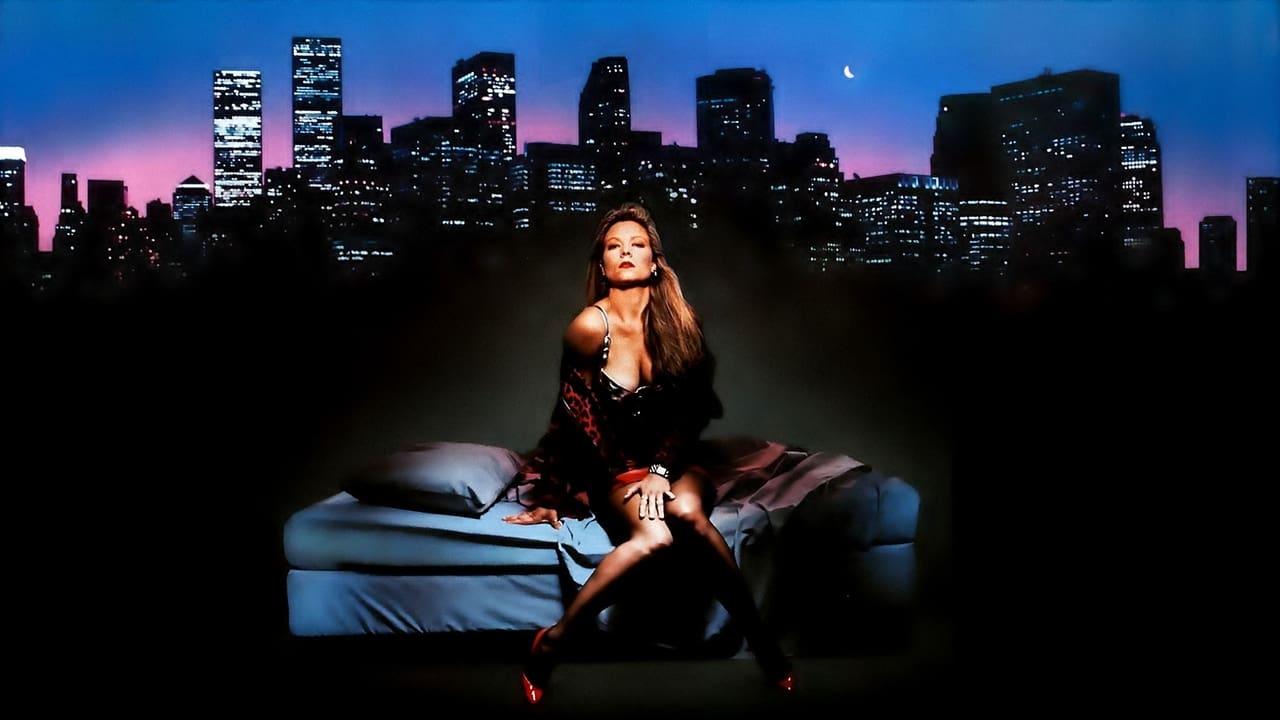

What unfolds is less a traditional narrative and more a raw, episodic journey through the grim realities faced by Liz (Theresa Russell, delivering a performance of astonishing candor and bravery), a street prostitute working the unforgiving sidewalks of Los Angeles. The film's most striking device, carried over from its stage origins, is Liz's direct address to the camera. She looks right at us, confiding, complaining, explaining the rules of the game, the dangers, the sheer grinding monotony, and the fleeting, often dark, moments of human connection (or lack thereof). This isn't the flamboyant, operatic Ken Russell of Tommy (1975) or The Lair of the White Worm (1988); here, his visual style is pared back, gritty, almost documentary-like at times, allowing the focus to remain squarely on Liz and her unflinching testimony.

The Power of Presence

Theresa Russell (no relation to the director, a fact often needing clarification back in the day) is the absolute anchor of the film. It’s a performance devoid of vanity, showcasing Liz's resilience, her weariness, her cynicism, and the buried vulnerability beneath the hardened exterior. She makes Liz utterly believable, navigating encounters with a variety of 'johns' – some pathetic, some dangerous, almost none understanding the woman standing before them. Her direct-to-camera monologues feel less like exposition and more like urgent, necessary confessions whispered in the dark. It's through her gaze that we experience the degradation, the fleeting moments of dark humour used as a shield, and the constant, simmering threat of violence. Does this constant breaking of the fourth wall fully succeed? For the most part, yes. It forces an intimacy, a confrontation, preventing the viewer from easily distancing themselves from Liz's reality. It feels less like a gimmick and more like the core of the film's identity.

Truth in Advertising, Trouble at the Box Office

Of course, that title caused immediate problems. The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) balked, leading distributor Trimark Pictures to devise one of the era's more awkward alternative titles for advertising: If You Can't Say It, Just See It. It’s a fascinating footnote, highlighting the nervousness surrounding the film’s unvarnished approach. This wasn't designed for mass appeal; it was a deliberately confrontational piece shot on a relatively low budget (around $1.3 million). You feel that constraint in the film's texture – the grainy nighttime shots of LA, the focus on character over spectacle. Supporting players like Benjamin Mouton as Liz's volatile pimp, Blake, and Antonio Fargas (forever Huggy Bear from Starsky & Hutch) in a smaller role, effectively sketch the harsh ecosystem Liz inhabits, but it remains firmly Theresa Russell's film.

Beyond the Shock Value

Decades removed from its initial release and the minor controversy it stirred, how does Whore hold up? It remains a potent, often uncomfortable watch. Its power lies not in titillation (there’s precious little of that) but in its bleak insistence on showing the dehumanizing aspects of the trade. It refuses easy answers or sentimentality. Russell’s direction, while restrained for him, still finds moments of stark visual poetry in the urban decay. The film asks us to simply look – to look at Liz not as a symbol or a stereotype, but as a person trapped in a brutal cycle. Does the episodic structure sometimes feel repetitive? Perhaps. Is the film relentlessly downbeat? Absolutely. But its honesty, particularly Theresa Russell's unwavering performance, lingers.

It’s not a film one watches for escapism; it's the antithesis of the glossy Hollywood product that dominated the multiplexes then and now. It feels like a dispatch from a different, grimier reality, captured on flickering videotape. I remember renting it, perhaps driven by the provocative title or curiosity about Ken Russell tackling such grounded material, and feeling profoundly unsettled afterward. It wasn't 'entertaining' in the conventional sense, but it was undeniably arresting.

Rating: 7/10

Whore earns its score through the sheer force and commitment of Theresa Russell's central performance and Ken Russell's brave, unblinking direction. It successfully deglamorizes its subject matter, presenting a raw slice-of-life that contrasts sharply with more palatable cinematic portrayals. While its unrelenting bleakness and episodic nature might not appeal to everyone, its confrontational style and powerful lead turn make it a significant, if challenging, piece of early 90s independent filmmaking. It remains a film that stares back at you, demanding you acknowledge the harsh reality it depicts, long after the tape has rewound.