### The Unseen Thread: Reflecting on Kieślowski's The Double Life of Véronique

There are films that entertain, films that thrill, and then there are films that simply haunt you, long after the VCR whirred to a stop and the tape was ejected. Krzysztof Kieślowski's The Double Life of Véronique (1991) belongs squarely in that last category. It arrived not with the bombast of a blockbuster, but with the quiet intensity of a whispered secret, a cinematic poem exploring the invisible threads that might connect us across continents and choices. Finding this gem nestled perhaps in the 'Foreign Films' section of the local video store felt like uncovering something precious, a stark contrast to the louder fare dominating the shelves, demanding a different kind of attention, a deeper kind of viewing.

Two Souls, One Essence

The premise itself is deceptively simple, yet profoundly resonant. We follow two young women, Weronika in Poland and Véronique in France, both musicians, both left-handed, both possessing a similar heart condition, and both played with astonishing grace by Irène Jacob. They share an uncanny resemblance and fleeting moments of intuition, sensing each other's presence across the miles without ever truly understanding why. A brief, almost subliminal glimpse during a political protest in Krakow is their only tangible intersection, yet their lives seem to echo one another – joys, sorrows, artistic passions, vulnerabilities. Kieślowski, working with his longtime collaborator Krzysztof Piesiewicz on the script, isn't interested in explaining the connection, but rather in exploring the feeling of it, the poignant mystery of lives lived in parallel.

A Visual and Aural Dreamscape

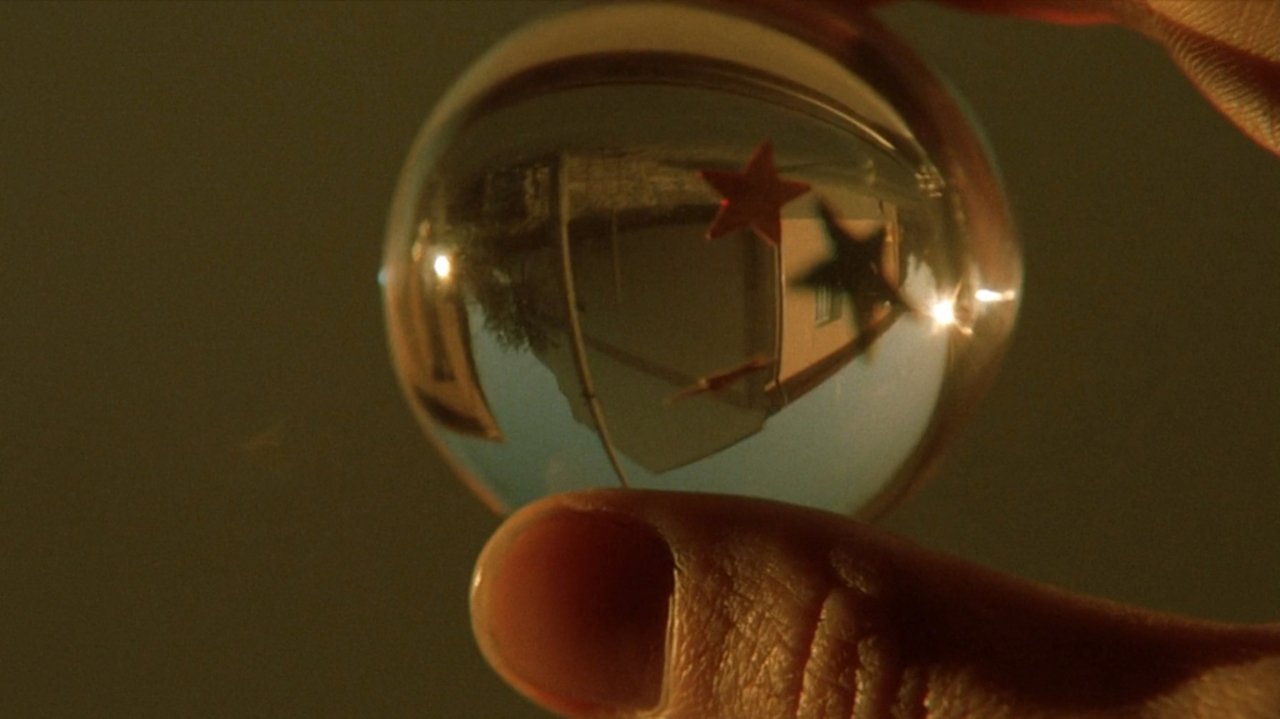

This isn't a film driven by plot mechanics; it's propelled by mood, atmosphere, and profound visual poetry. Director Krzysztof Kieślowski, who had already stunned audiences with the monumental The Decalogue series, crafts a world shimmering with ambiguity and ethereal beauty. The cinematography by Sławomir Idziak is legendary, employing distinctive golden filters that bathe scenes in an almost otherworldly light, enhancing the sense of warmth, memory, and fragile existence. Close-ups linger on Jacob's expressive face, capturing micro-emotions that speak volumes. Every frame feels deliberate, composed like a painting, inviting contemplation.

Equally crucial is the score by Zbigniew Preisner. His haunting melodies, particularly the piece central to the narrative composed by the fictional Van den Budenmayer, become almost another character in the film. The music underscores the themes of beauty, loss, and the transcendent power of art, weaving through the narrative like the unseen connection between the two women. It’s one of those scores that became instantly recognisable, synonymous with a certain kind of thoughtful, European cinema that gained traction in the early 90s.

The Heart of the Film: Irène Jacob

At the absolute center of Véronique is the luminous performance by Irène Jacob. Winning Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival for this role was thoroughly deserved. She embodies both Weronika and Véronique with such subtle differentiation and profound empathy. Weronika bursts with vibrant, almost naive passion, while Véronique carries a more melancholic, searching quality, perhaps tempered by an unconscious sense of loss or warning inherited from her Polish counterpart. Jacob conveys the weight of intuition, the physical fragility, and the deep artistic sensitivity of both women with breathtaking authenticity. It’s a performance free of affectation, grounded in emotional truth, making the fantastical premise feel utterly believable on an intuitive level. Watching her navigate these parallel existences is the film's most captivating element.

Echoes in the Aisles

Remember finding those slightly more esoteric tapes back in the day? The Double Life of Véronique represents that specific joy of discovery. It wasn’t the tape you grabbed for a Friday night pizza party, but the one you rented when you were looking for something more, something that might stick with you. This film, a Polish-French co-production, marked Kieślowski's successful transition to more international filmmaking, paving the way for his acclaimed Three Colours Trilogy (Blue, White, Red). It’s fascinating to think that Kieślowski initially considered having the characters meet more substantially, but ultimately opted for the more elusive, glancing encounter, preserving the film’s potent sense of mystery. This choice, alongside Idziak's experimental use of filters (sometimes literally holding different coloured glass elements in front of the lens), contributes significantly to the film’s unique, dreamlike quality.

What Lingers After the Credits?

Does the film offer easy answers about fate, destiny, or parallel universes? Absolutely not. And that's precisely its strength. It poses questions rather than providing solutions. What does it mean to feel connected to something or someone you can't explain? How do small choices ripple outwards, creating different potential lives? Is there a comfort, or a sadness, in knowing that perhaps another version of ourselves exists, making different choices, experiencing different joys and sorrows? The film resonates with these subtle, often unanswerable questions about the human condition, the roads not taken, and the mysterious synchronicities that sometimes touch our lives.

---

Rating: 9/10

The Double Life of Véronique earns this high mark for its exquisite artistry, its profound emotional depth, and Irène Jacob's unforgettable performance. It’s a film that achieves a rare synthesis of visual beauty, evocative music, and thematic resonance. While its deliberate pacing and ambiguity might not appeal to everyone seeking straightforward narrative, its power lies in its ability to create a lasting, almost subconscious impression. It’s a masterclass in cinematic mood and a testament to Kieślowski's unique vision.

Final Thought: This is a film that rewards patience and contemplation, a haunting melody that stays with you, prompting reflections on the unseen connections that shape our fragile, beautiful lives. It remains a standout piece of early 90s art house cinema, a reminder of the depth and beauty waiting to be discovered on those old VHS shelves.