There are some films that don't just tell a story; they grab you by the collar and demand you bear witness. Derek Jarman's 1991 adaptation of Christopher Marlowe's Edward II is precisely that kind of film – a viewing experience that, once encountered on some perhaps unassuming VHS tape back in the day, likely scorched itself into memory. It wasn't your typical Friday night rental fodder, nestled perhaps uneasily between glossy Hollywood thrillers and big-budget fantasies. Instead, it felt like a raw, vital transmission, bristling with an energy that was both historical and startlingly immediate.

A Crown, A Lover, A Kingdom Undone

Pulling from Marlowe's late 16th-century play, Jarman confronts the turbulent reign of England's King Edward II (Steven Waddington), whose passionate, all-consuming love for the low-born Piers Gaveston (Andrew Tiernan) alienates his Queen, Isabella (Tilda Swinton), and infuriates the entitled nobility, led by the calculating Mortimer (Nigel Terry, unforgettable years earlier as King Arthur in Excalibur (1981)). The core narrative remains: a king's disastrous favouritism leads to rebellion, deposition, and a truly horrific end. But this is no staid costume drama. Jarman, ever the iconoclast, rips the story from its expected historical setting and thrusts it into a Brechtian landscape of minimalist sets, modern dress (often military surplus or sharp suits mingling with crowns), and deliberate anachronisms.

Jarman's Vision: Anger and Anachronism

This stylistic choice isn't mere provocation; it's central to the film's power. By stripping away the comforting tapestry of period detail, Jarman forces us to confront the raw emotions and political machinations at play. The sparse, often brutalist settings – concrete walls, empty stages – throw the characters and their conflicts into stark relief. This wasn't simply an aesthetic preference; working with a relatively modest budget (estimated around £800,000 or $1.2 million), Jarman turned constraint into potent expression. It's a reminder of how resourceful filmmaking thrived, even necessity breeding invention, long before CGI offered infinite, sometimes soulless, possibilities. I distinctly remember the cover art for the VHS likely reflecting this starkness, offering little clue to the firestorm within, making the discovery all the more impactful.

Crucially, Jarman connects Edward's persecution directly to the contemporary political climate of Thatcher's Britain and, specifically, the infamous Section 28 legislation which prohibited the "promotion" of homosexuality. Released in 1991, the film resonates with the anger and defiance of the LGBTQ+ rights movement. In a stroke of guerilla genius, Jarman even cast activists from the direct-action group OutRage! as Edward's loyal soldiers, their modern protest banners seamlessly integrated into scenes of medieval rebellion. It transforms Marlowe's tragedy into a searing, timely political statement about oppression, power, and the state's interference in personal lives. Doesn't that theme still echo with uncomfortable familiarity today?

Performances Forged in Fire

The casting feels inspired. Steven Waddington, in a breakthrough role, portrays Edward not merely as a weak king, but as a man utterly consumed by love, defiant in his affections even as his kingdom crumbles. There's a raw vulnerability beneath the petulance, a humanity that makes his eventual fate all the more wrenching. Opposite him, Andrew Tiernan as Gaveston is magnetic – charismatic, ambitious, and embodying the perceived threat to the established order.

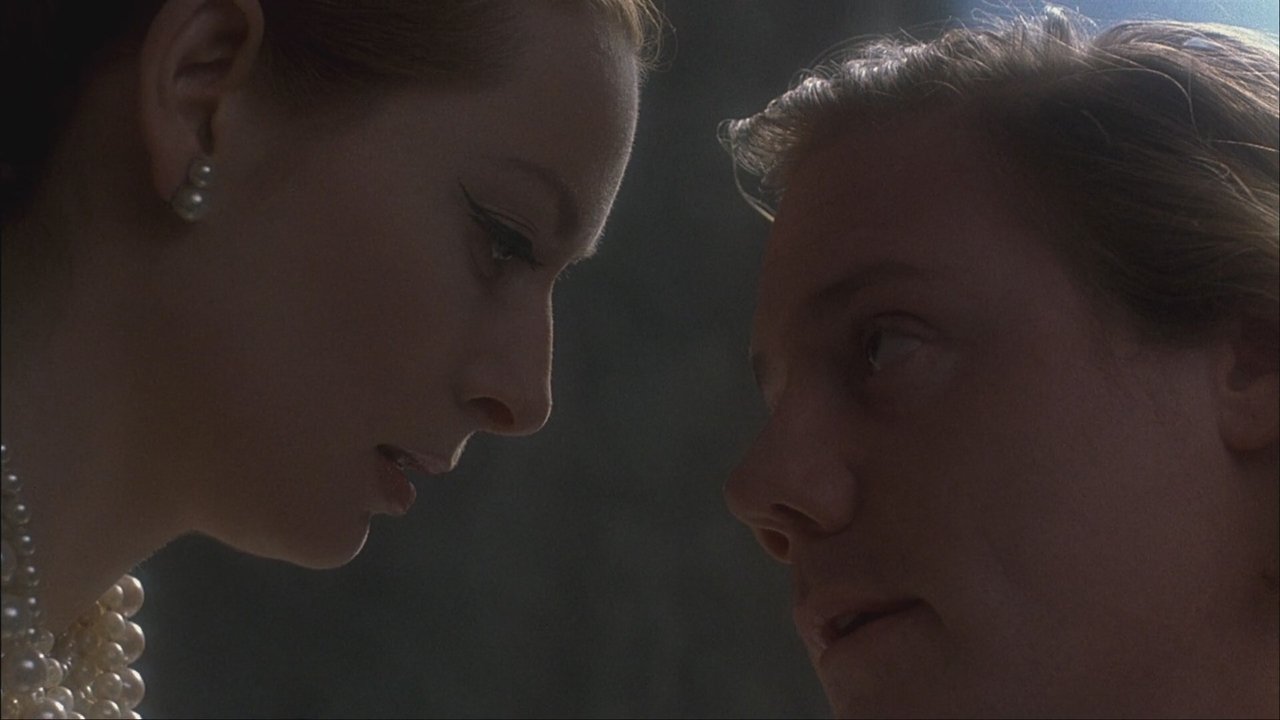

And then there is Tilda Swinton. As Queen Isabella, she delivers a performance of staggering power and transformation. Initially the wronged, neglected wife, her Isabella evolves into a figure of icy resolve and chilling vengeance. Swinton, even then radiating that unique, almost otherworldly screen presence she'd hone in later films like Orlando (1992) (another anachronistic gem) and beyond, conveys vast reserves of pain, pride, and calculated fury, often with just a look or a shift in posture. Her journey from victim to aggressor is terrifyingly believable. It's a performance that proves truthful acting doesn’t need elaborate sets; it needs commitment and insight.

Beyond the Expected Narrative

Jarman, who was battling HIV during the film's production and tragically passed away just three years later, infused Edward II with a palpable sense of urgency and mortality. The film doesn't shy away from the brutality inherent in the story – the violence is often stylized but deeply unsettling, culminating in Edward's infamously gruesome demise (handled here with suggestion rather than explicit gore, yet losing none of its horror). The use of modern elements, like Gaveston's Walkman or the soldiers' combat gear, constantly jolts the viewer, preventing any comfortable historical distance. What lingers most after the film ends is perhaps this refusal to let the past remain buried, insisting on its relevance to the present.

Adding another layer of poignant beauty is Annie Lennox's haunting rendition of Cole Porter's "Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye" over the end credits. It’s a moment of quiet sorrow after the preceding storm, a perfect, melancholic grace note that allows the film’s themes of love, loss, and persecution to settle. It’s one of those soundtrack choices that feels utterly inseparable from the film itself once you’ve heard it.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's audacious artistic vision, its powerful and committed performances, and its brave political heart. Jarman crafts a work that is challenging, sometimes stark, but ultimately unforgettable. It's not an easy watch, nor was it ever intended to be. Its minimalist aesthetic and deliberate anachronisms might not appeal to everyone seeking traditional period drama, but its raw emotional power and fierce intelligence are undeniable. The points are earned through its sheer bravery, the strength of the central trio's acting (especially Swinton's), and Jarman's unwavering commitment to his unique interpretation, transforming historical text into urgent contemporary commentary.

Edward II stands as a landmark of 90s independent British cinema and a potent testament to Derek Jarman's singular talent. It’s a film that reminds us how cinema, even on a modest budget, can be a weapon, a poem, and a primal scream all at once – a VHS discovery that likely left many viewers profoundly shaken and thinking long after the tape ejected.