Okay, fellow tape travellers, pull up a comfy chair. Sometimes, digging through the archives unearths something far stranger and more demanding than the usual neon-soaked action flick or synth-scored slasher. Today, we’re looking at a ghost, a myth whispered about in hushed tones by serious cinephiles long before the internet made everything instantly accessible: Jacques Rivette's Out 1. While conceived and shot in the fiery aftermath of May 1968 France, a shorter, somewhat more digestible version (dubbed Out 1: Spectre) finally flickered onto screens and, eventually, into the realm of the dedicated home video hunter around 1990. Finding this wasn't like grabbing the latest Schwarzenegger release; it felt like uncovering a hidden text, a secret map to a different kind of cinema.

A Labyrinth of Whispers

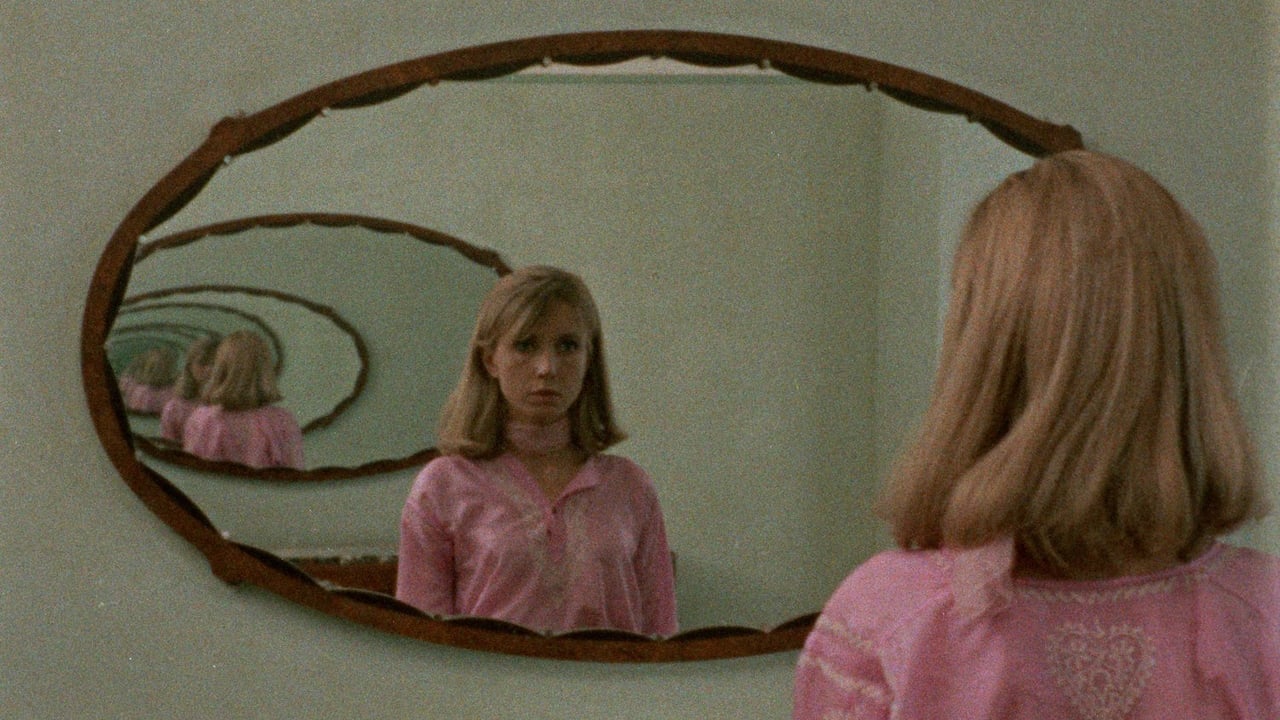

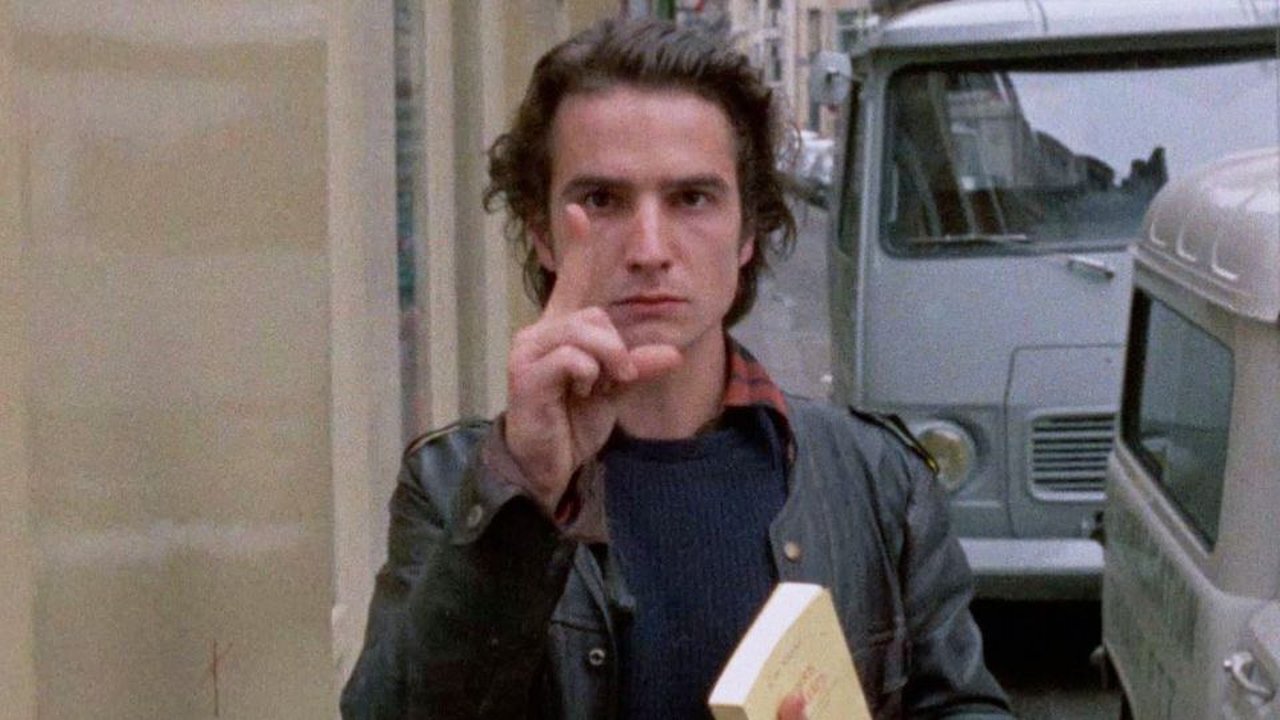

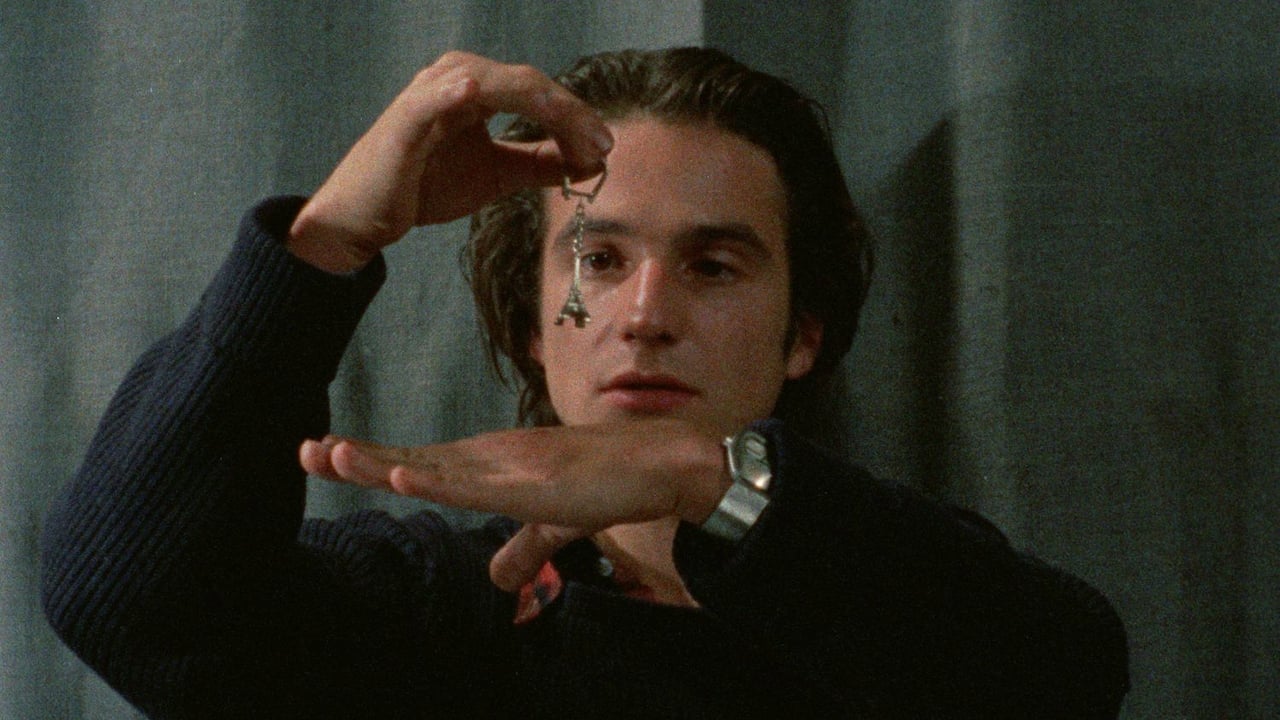

Trying to describe the "plot" of Out 1 feels like trying to cup smoke in your hands. Originally running nearly 13 hours (the legendary Noli Me Tangere version, rarely seen until the 21st century), the 4.5-hour Spectre cut still offers an experience unlike almost anything else. We follow two separate theatre groups in Paris rehearsing classical plays (Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound and Seven Against Thebes). Simultaneously, we track Colin (Jean-Pierre Léaud, forever the face of the French New Wave after The 400 Blows), a deaf-mute panhandler who receives cryptic messages hinting at a secret society, possibly linked to Honoré de Balzac's History of the Thirteen. And then there’s Frédérique (Juliet Berto), a small-time thief who pilfers some of these letters herself.

These threads barely intersect initially. Instead, Rivette immerses us in process: the actors' exercises, their improvisations, their frustrations, their breakthroughs. We watch Colin painstakingly try to decipher codes, wandering through Paris like a phantom. Frédérique drifts through encounters, seemingly aimless but drawn towards the unseen conspiracy. It’s less a narrative drive and more an accumulation of moments, gestures, and atmospheres. The film breathes Paris in the early 70s – not the tourist postcard, but the real, lived-in city spaces, the cafés, the rehearsal rooms, the streets.

The Unfolding Experiment

What makes Out 1 so fascinating, and admittedly challenging, is Rivette's radical approach. Much of the dialogue and action was improvised by the actors within a loose framework. This wasn't just a gimmick; it was integral to the film's exploration of paranoia, communication breakdown, and the search for meaning in a fragmented world. The theatrical rehearsals become mirrors for the hidden machinations Colin pursues – are both just elaborate games? Is the conspiracy real, imagined, or a collective projection? The film famously grew out of the post-'68 disillusionment, a sense that grand narratives had collapsed, leaving behind whispers and conspiracies.

Watching it today, especially thinking back to encountering even the Spectre version on some rare tape or at a revival house screening in the 90s, feels like an archaeological dig. The grain of the 16mm film, the unvarnished naturalism of the performances – it’s utterly removed from the polished sheen of mainstream 80s/90s cinema. Léaud is captivating, his physical performance communicating a desperate yearning for connection and understanding. Berto embodies a cool, elusive counterpoint, while veterans like Michael Lonsdale (later Hugo Drax in Moonraker (1979)) bring a grounded weariness to the theatrical world. The commitment of the entire ensemble to Rivette's demanding, open-ended process is palpable.

Beyond the Runtime: A Test of Endurance and Reward

Let's be honest: Out 1 (in either form) is not casual viewing. It requires patience, concentration, and a willingness to let go of conventional storytelling expectations. There are long stretches where seemingly little "happens." Yet, stick with it, and a strange magic takes hold. You become attuned to the film's peculiar rhythms, the subtle shifts in mood, the recurring motifs. The lengthy rehearsal scenes, initially perhaps tedious, become fascinating studies of creative collaboration and psychological interplay. The city itself becomes a character, its geography shaping the elusive narrative.

Its elusiveness was part of its legend. This wasn't something you'd find nestled between Die Hard (1988) and Home Alone (1990) at Blockbuster. Tracking down Out 1 often involved navigating specialist catalogues, film society connections, or maybe even tape trading – a very different kind of nostalgic quest. The sheer effort required to see it amplified its mystique. It was a testament to the idea that cinema could be something other than easily consumed entertainment; it could be an immersive, sometimes baffling, but ultimately profound experience.

Rating: 8/10

This rating comes with a significant asterisk. For its sheer audacity, its unique exploration of performance and paranoia, and its status as a landmark of experimental narrative cinema, Out 1 is exceptional. The commitment of Rivette and his cast is undeniable, creating moments of startling intimacy and unsettling ambiguity. However, its extreme length (even in the shorter cut) and deliberately opaque structure make it a formidable challenge. This score reflects its artistic importance and the hypnotic power it holds for the patient viewer, acknowledging it’s far from universally accessible or traditionally "entertaining." It earns its place not through easy thrills, but through the lingering questions and unsettling atmosphere it cultivates.

Out 1 remains less a movie to be simply watched, and more an environment to be inhabited, a puzzle box that perhaps resists complete solution. What lingers isn't a clear story, but the feeling of having glimpsed hidden connections, the hum of secrets just beneath the surface of the everyday – a truly rare find from the vaults.