There are films that wash over you, entertaining distractions easily rewound and rewatched. And then there are films like Maurice Pialat's Under the Sun of Satan (1987), cinematic experiences that feel less like watching and more like enduring a spiritual crucible. Forget the neon glow and synth scores often associated with 80s VHS finds; this is something far bleaker, more demanding, lodging itself under your skin with the discomfort of a profound, unanswered question. It's the kind of tape you might have found tucked away in the 'World Cinema' section of a particularly well-stocked video store, promising something entirely different from the action and comedy aisles.

A Landscape of Spiritual Anguish

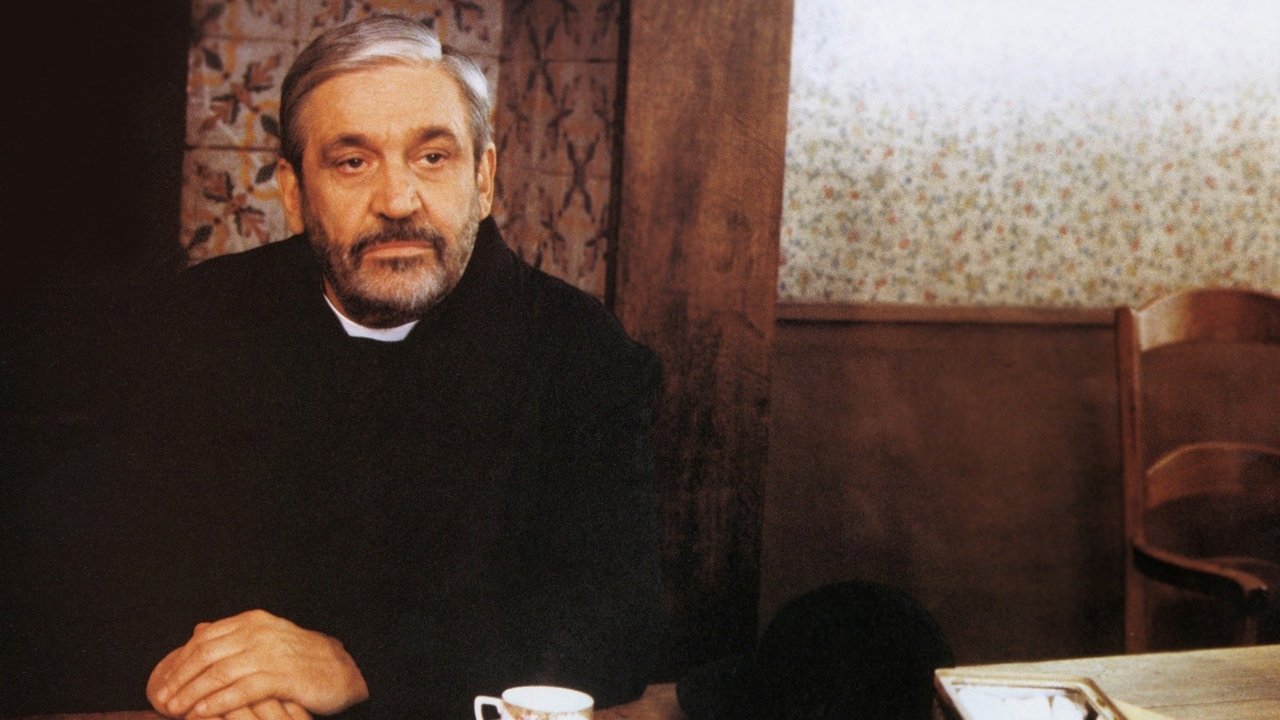

Adapted from the novel by Georges Bernanos (whose work also inspired Robert Bresson's austere masterpiece Diary of a Country Priest), Sous le soleil de Satan, as it's known in its native French, plunges us into the muddy, desolate landscape of rural France. Here, Father Donissan, portrayed by a truly monumental Gérard Depardieu, wrestles not just with the sins of his parishioners but with the terrifying weight of his own faith, doubt, and perceived inadequacy. He’s a man physically imposing yet spiritually fragile, convinced of his unworthiness, tormented by visions and a palpable sense of battling forces beyond human comprehension. Pialat, known for his unflinching realism and often confrontational style (he previously directed Depardieu in Loulou (1980) and Sandrine Bonnaire in À nos amours (1983)), offers no easy solace or cinematic comfort. The world here is harsh, unforgiving, and seemingly abandoned by grace.

The Devil in the Details

Into Donissan's tormented world steps Mouchette (Sandrine Bonnaire), a young woman whose transgressions – including murder and an incestuous relationship – seem to embody a chilling, almost feral amorality. Their encounters are charged with a disturbing intensity. Is Donissan a potential conduit for grace, or is he dangerously susceptible to the very darkness he seeks to confront? The film walks a knife's edge, refusing easy categorization of sainthood or damnation. One unforgettable sequence finds Donissan literally confronting Satan on a lonely road – a scene fraught with theological ambiguity and psychological terror. Does he truly possess powers to discern sin and offer absolution, or are these delusions born of extreme asceticism and spiritual despair? Pialat leaves these questions hanging, forcing us to grapple with the terrifying possibility that the lines between divine insight and madness are perilously thin.

Performances Forged in Fire

The film rests heavily on the shoulders of its leads, and they deliver performances of staggering power. Gérard Depardieu, an actor capable of immense charisma, here channels a raw, almost unbearable vulnerability. His Father Donissan is a man visibly buckling under spiritual pressure, his physical bulk seeming to contain an imploding soul. It’s a performance devoid of vanity, deeply unsettling in its authenticity. Equally devastating is Sandrine Bonnaire as Mouchette. Following her haunted turn in Agnès Varda's Vagabond (1985), Bonnaire embodies Mouchette with a chilling mixture of defiance, desperation, and unnerving emptiness. She isn’t simply 'evil'; she’s a damaged soul navigating a world that offers her little but judgment and exploitation. Their scenes together crackle with unspoken tension and profound spiritual stakes. Even Pialat himself steps before the camera as Dean Menou-Segrais, Donissan’s weary, perhaps more pragmatic superior, adding another layer of grounded weariness to the proceedings. Pialat was known for pushing his actors, sometimes to breaking point, and the raw, unvarnished emotion on screen feels less like acting and more like witnessing genuine human struggle.

A Controversial Triumph

Finding Under the Sun of Satan on VHS back in the day would have been a commitment, a far cry from grabbing the latest Stallone or Schwarzenegger flick. It demanded patience and a willingness to be deeply unsettled. This challenging nature famously boiled over at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival. When the film was awarded the prestigious Palme d'Or, the decision was met with boos and whistles from parts of the audience. Pialat's response became legendary: stepping up to the microphone, he defiantly raised his fist and declared, "If you don't like me, I can tell you I don't like you either!" It was a moment perfectly encapsulating the film's own confrontational spirit – uncompromising, difficult, yet undeniably powerful. This wasn't filmmaking designed to soothe or entertain in the conventional sense; it was an artistic statement demanding engagement on its own stark terms.

The Lingering Chill

What stays with you long after the credits roll on Under the Sun of Satan? It’s not a clear message or a comforting resolution. It’s the atmosphere of profound spiritual unease, the stark beauty of the desolate landscapes, and the haunting power of Depardieu and Bonnaire’s performances. It’s a film that poses fundamental questions about the nature of faith, the pervasiveness of sin, and the possibility of grace in a seemingly indifferent world, but offers no easy answers. Can true faith exist without profound doubt? Where does divine intervention end and delusion begin? Pialat forces us, alongside Father Donissan, to stare into that abyss.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable artistic merit, its powerhouse performances, and its courageous, uncompromising vision. It’s a demanding, often grueling watch, lacking the immediate accessibility of many 80s classics revered on VHS Heaven. Its bleakness and deliberate pace won't be for everyone, preventing a higher score for general rewatchability. However, its thematic depth and raw emotional power are undeniable, marking it as a significant, challenging piece of 80s European cinema. The justification lies in its sheer artistic integrity and the unforgettable, haunting quality of its central performances and existential questions.

Under the Sun of Satan remains a potent, unsettling experience – a reminder that cinema, even from the vibrant VHS era, could also be a place for profound, difficult, and ultimately unforgettable spiritual inquiry. It asks much of its audience, but the encounter lingers, cold and thought-provoking, long after the tape stops rolling.