It’s a strange thing, isn’t it? How certain tapes on the video store shelf seemed heavier than others, not physically, but emotionally. Amidst the explosions and neon glows, there’d be these dramas, often adaptations, carrying the weight of significance. The 1985 television film version of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman was precisely that kind of tape – a promise of profound, perhaps uncomfortable, truth nestled between the action flicks and comedies. Seeing it wasn't casual viewing; it felt like an event, a direct broadcast of raw, unvarnished humanity into our living rooms.

The Weight of a Dream Deferred

Directed by the acclaimed German filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff, fresh off the Palme d'Or win for The Tin Drum (1979), this adaptation doesn't shy away from the claustrophobia and simmering desperation inherent in Miller's text. Schlöndorff, perhaps bringing an outsider's clarity to this quintessentially American tragedy, frames the Loman household not just as a setting, but as a psychological prison. The walls feel thin, the past bleeds into the present through Willy’s fractured recollections, and the suffocating weight of expectation hangs heavy in the air. Miller himself adapted his Pulitzer Prize-winning play for this production, ensuring a potent fidelity to the source material that resonates deeply. It’s less about opening up the play visually and more about focusing intensely on the faces, the gestures, the crushing intimacy of familial disappointment.

Hoffman’s Haunting Embodiment

At the heart of it all is Dustin Hoffman’s Willy Loman. Having already triumphed in the role on Broadway in 1984, Hoffman doesn't just play Willy; he inhabits him with a devastating totality. This isn't the bombastic failure often depicted; Hoffman’s Willy is smaller, more tragically fragile. You see the flickering remnants of the hopeful young man beneath the exhausted, bewildered shell of the present. His optimism is a desperate reflex, his anger born of confusion as much as pride. There’s a scene where Willy, trying to recount a moment of minor success, gets lost in his own fragmented narrative, his eyes darting, searching for a truth that keeps slipping away – it’s a masterclass in portraying cognitive and emotional disintegration. It’s a performance driven by a long-held passion; Hoffman reportedly carried a desire to play Willy for years, and that dedication burns through the screen, earning him a well-deserved Emmy and Golden Globe.

A Family Fractured by Illusion

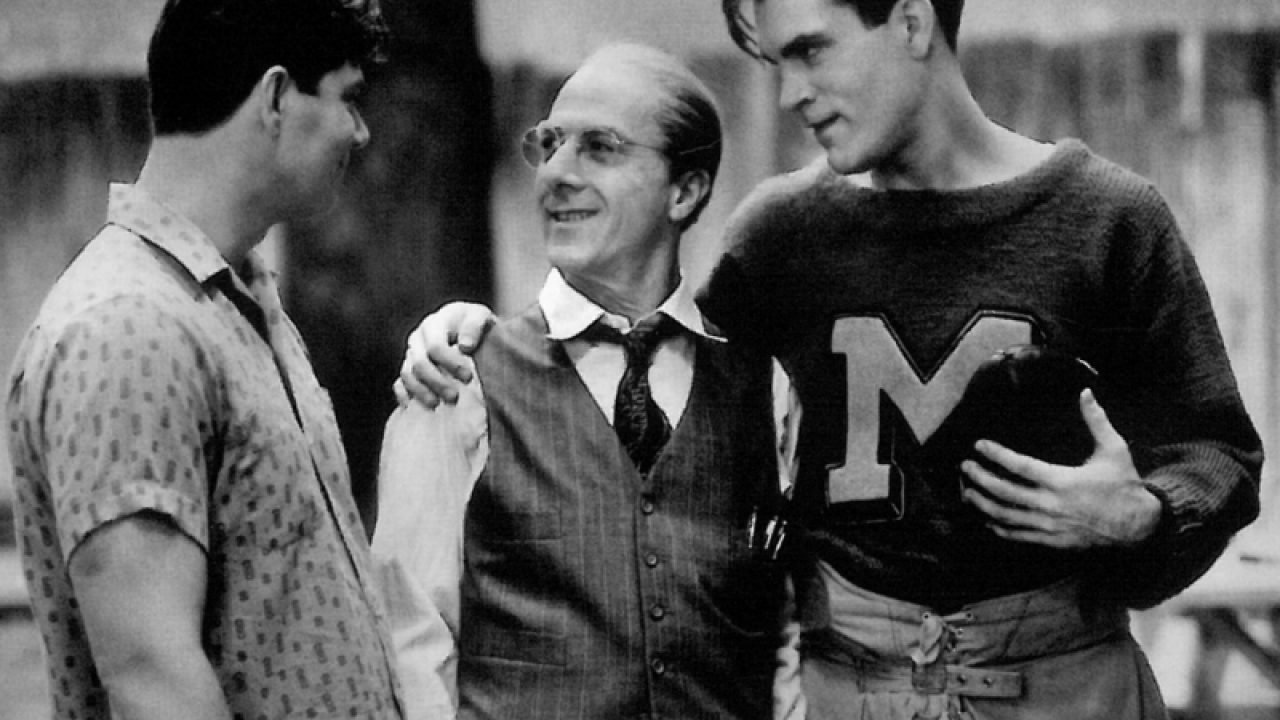

Surrounding Hoffman is an ensemble that meets his intensity. Kate Reid as Linda Loman is heartbreaking. She’s not merely a long-suffering wife; Reid imbues Linda with a fierce, almost terrifying loyalty, her famous "Attention must be paid" speech delivered not as a plea, but as a righteous demand born from witnessing Willy’s slow-motion collapse. Her quiet devastation anchors the family’s turmoil. And then there’s John Malkovich as Biff. Fresh off his star-making turn in Places in the Heart (1984), Malkovich brings his signature coiled energy to the role. His Biff is a raw nerve, vibrating with resentment, love, and the crushing weight of his father’s expectations and his own perceived failures. The confrontation scenes between Hoffman and Malkovich crackle with an almost unbearable tension – two men drowning in unspoken history and shared delusion. Stephen Lang, often excellent in supporting roles throughout the 80s and 90s (think Manhunter or Gettysburg), effectively captures Happy’s desperate need for approval and his inherited capacity for self-deception.

More Than Just a Taped Play

While retaining the theatrical power of Miller's dialogue, Schlöndorff uses the medium of television film effectively. Close-ups amplify the emotional nuance, catching the flicker of doubt in Willy’s eyes or the tremor in Linda’s hand. The transitions between past and present, often achieved with simple shifts in lighting or staging within the same set, feel fluid yet disorienting, mirroring Willy’s own mental state. This wasn't filmed on grand stages but often utilized real locations or carefully constructed sets that emphasized the modest, hemmed-in reality of the Lomans' lives, contrasting sharply with Willy's inflated dreams. It’s a production that understands the power is in the words and the performances, using the camera to focus our attention relentlessly on the human cost of the American Dream gone sour. For many, seeing this production on CBS, possibly recorded onto a T-120 VHS tape, was their first encounter with Miller's monumental work, bringing heavyweight drama directly to the people.

Retro Fun Facts Woven In

The commitment to authenticity was palpable. Arthur Miller's presence adapting his own work lent an undeniable authority. Volker Schlöndorff's direction avoided flashy cinematic tricks, respecting the material's stage origins while using the camera's intimacy to draw viewers closer to the characters' inner turmoil than a theatre seat might allow. The critical acclaim was significant, netting numerous Emmy wins beyond Hoffman's, including Outstanding Drama/Comedy Special and Outstanding Directing for Schlöndorff, cementing its status as a landmark television event of the era. Finding this tape felt like discovering something important, a serious piece of art preserved on magnetic tape.

The Enduring Echo

Watching Death of a Salesman today, especially this 1985 version, feels less like mere nostalgia and more like confronting timeless questions. What happens when the societal promises we build our lives around prove hollow? How do familial expectations shape, and sometimes break, us? Willy Loman’s tragedy, his inability to reconcile his dreams with reality, feels hauntingly relevant. Hoffman’s performance remains a towering achievement, capturing the everyman swallowed by forces he can neither understand nor control. It’s a heavy watch, no doubt, the kind of film that sits with you long after the VCR clicks off.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the sheer power of the source material combined with truly exceptional, career-defining performances, particularly from Hoffman and Malkovich. Schlöndorff's sensitive direction and Miller's own adaptation create a definitive screen version that sacrifices none of the play's emotional weight. It’s a masterful translation of stage to screen, losing perhaps only the raw, immediate energy of live theatre but gaining an intimate intensity that’s profoundly affecting.

It remains a stark, essential piece of American drama, captured with integrity and performed with devastating truth – a heavyweight title that earned its place on the top shelf.