It’s a rare thing, isn’t it? To encounter a film from the neon-drenched heart of the 80s that bypasses the era's typical cinematic language of spectacle and escapism, aiming instead for something devastatingly human, something that settles deep in your bones and stays there. El Norte (1983) is precisely such a film. Finding this one on the shelves, perhaps tucked away from the action blockbusters, felt like uncovering a secret – a whispered story demanding to be heard amidst the noise. It wasn't your usual Friday night rental fodder; it was an experience, beautifully rendered yet profoundly unsettling.

A Journey Etched in Hope and Sorrow

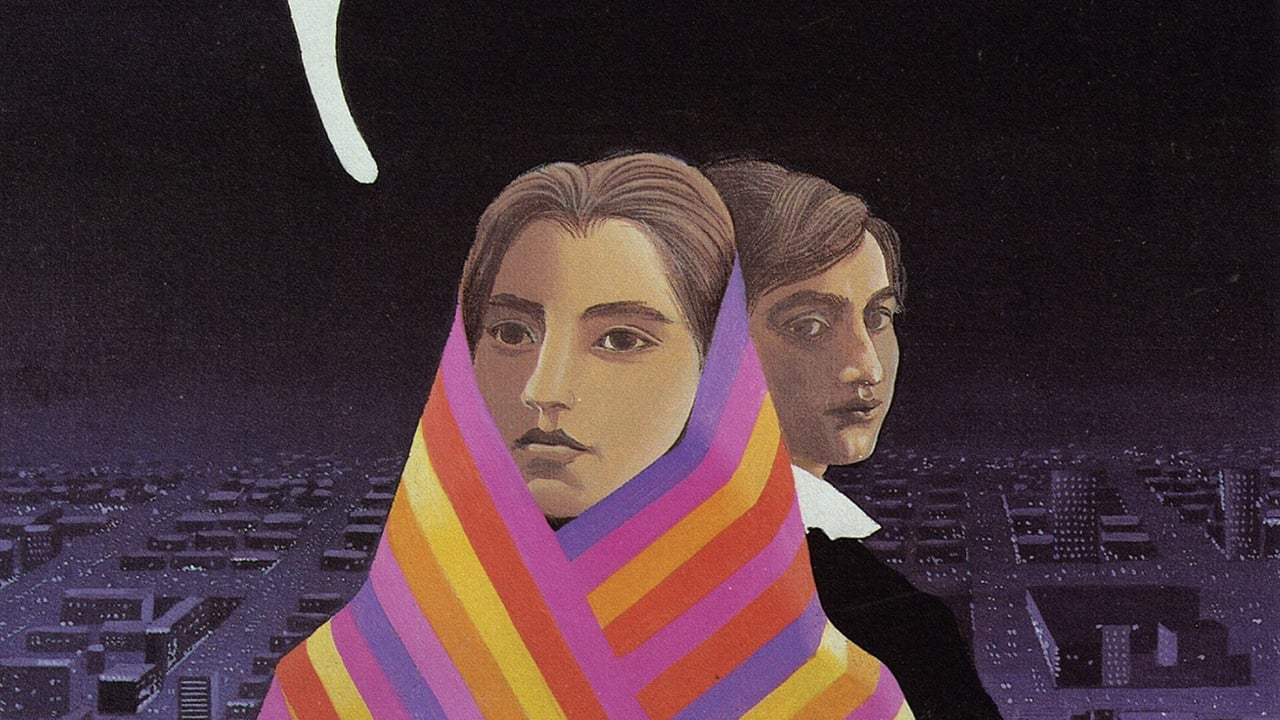

What strikes you immediately about El Norte, directed with astonishing grace and empathy by Gregory Nava (who co-wrote the screenplay with Anna Thomas), is its almost classical structure, unfolding like a triptych of hope, hardship, and heartbreaking reality. We begin in a small Indigenous village in Guatemala, painted with strokes of both lyrical beauty and simmering political violence. This isn't just backdrop; it’s the soil from which our protagonists, teenage siblings Enrique (David Villalpando) and Rosa (Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez), are brutally uprooted. Their journey north – el norte – becomes not just a geographical migration, but a passage through layers of exploitation and the erosion of dreams.

The film doesn't shy away from the harshness. The escape from Guatemala is fraught with peril, their time navigating the complex and often predatory landscape of Mexico is tense, and the arrival in the promised land of Los Angeles presents its own unique set of dehumanizing challenges. What makes this narrative so compelling, so utterly gut-wrenching, isn't just the depiction of hardship, but the unwavering focus on the siblings' bond and their quiet dignity in the face of relentless adversity.

Faces That Haunt Long After the Credits Roll

The power of El Norte rests significantly on the shoulders of its two leads. Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez as Rosa is luminous, embodying a resilience that’s constantly tested but never entirely extinguished. Her eyes convey worlds of fear, hope, and weariness. David Villalpando as Enrique captures the weight of responsibility, the desperate need to protect his sister and forge a new life, even as the dream curdles around him. Their performances are remarkably naturalistic, free from affectation. You don’t feel like you’re watching actors; you feel like you’re bearing witness to the lives of these two specific, unforgettable individuals. Their chemistry as siblings feels utterly authentic, making their shared moments of joy fleetingly precious and their struggles deeply personal. Even Ernesto Gómez Cruz, in his smaller role as their father Arturo, leaves an indelible mark early on, setting the stage for the tragedy to come.

It’s a testament to Nava’s vision and the actors’ commitment that these performances resonate so powerfully. It's worth remembering this was an independent production, made for a modest budget (reportedly under $1 million – pocket change even then!). Nava cast relatively unknown actors, adding to the film’s sense of realism. This wasn't Hollywood gloss; it felt raw, immediate.

Crafting Beauty from Brutality

Gregory Nava, who would later give us films like Mi Familia (1995) and Selena (1997), demonstrates an incredible command of tone here. The cinematography often juxtaposes the inherent beauty of the landscapes – the lush Guatemalan highlands, the vibrant chaos of Mexican border towns, the glittering, indifferent skyline of L.A. – with the ugliness of the human experiences unfolding within them. There's a painterly quality to some shots, bordering on magical realism, particularly in the early Guatemalan scenes, which makes the later descent into the harsh realities of undocumented life feel even more jarring.

The film faced significant challenges during production, including navigating difficult shooting locations across three countries with limited resources. Yet, this struggle seems embedded in the film's DNA, contributing to its authenticity. The infamous scene involving escaping tunnel rats, for instance, is rendered with a visceral horror that speaks volumes about the dehumanizing lengths people are forced to go to for survival. It’s a sequence that, once seen, is impossible to forget – a practical effect nightmare brought chillingly to life.

Retro Fun Facts: An Independent Spirit Triumphs

- El Norte was a true labor of love, funded independently after major studios passed. Its eventual success was a significant victory for independent filmmaking.

- The screenplay by Gregory Nava and Anna Thomas earned a surprise, but richly deserved, Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay in 1985 – a rare feat for such a low-budget, non-studio film, especially one featuring significant dialogue in K'iche' Maya and Spanish.

- Renowned critic Roger Ebert was an early and vocal champion of the film, giving it four stars and later adding it to his "Great Movies" list, which significantly boosted its visibility.

- The film's three-act structure ("Arturo," "El Coyote," "El Norte") mirrors the stages of the journey, giving it an epic, almost literary feel.

A Story Tragically Evergreen

Watching El Norte today, decades after its initial release on those hefty VHS tapes, its themes feel painfully relevant. The dreams and dangers faced by Enrique and Rosa echo in the headlines we still read. It’s a film that explores the immense human cost of displacement, the complexities of cultural identity, and the often-brutal disparity between the promise of "the North" and its reality. It forces us to ask: What drives someone to leave everything behind? And what is the true price of seeking a better life?

It doesn't offer easy answers. Instead, it presents a deeply empathetic portrait of human resilience and vulnerability. It’s not always an easy watch – its emotional weight is considerable – but it feels essential.

Rating: 9.5/10

This rating reflects the film's profound emotional impact, the stunning authenticity of its lead performances, Nava's masterful direction, and its groundbreaking status as a powerful, independent work that gave voice to experiences rarely seen on screen in the early 80s. It's visually beautiful, narratively compelling, and thematically resonant, justifying its place as a landmark of American independent cinema. The slight deduction acknowledges that its deliberate pacing and heavy subject matter demand a certain commitment from the viewer, but the reward is immense.

El Norte remains a vital, heartbreaking piece of cinema. It’s a film that transcends its era, a poignant reminder of shared humanity smuggled onto video store shelves, waiting to break the hearts and open the minds of those who dared to look beyond the blockbusters. It’s a journey that, once taken, stays with you.