There's a peculiar kind of dread that builds, almost imperceptibly at first, like static cling on a favourite old sweater. It starts with a misplaced twenty-dollar bill blown out a cab window, a simple mistake. But in Martin Scorsese's feverish 1985 odyssey After Hours, that small mishap is merely the loose thread that unravels an entire night, plunging an ordinary man into a surreal SoHo labyrinth from which escape seems increasingly impossible. Watching it again now, decades after first sliding that distinctive VHS tape into the VCR, the film retains its potent, darkly comic anxiety, a feeling both specific to its time and somehow eternally relevant.

One Wrong Turn After Another

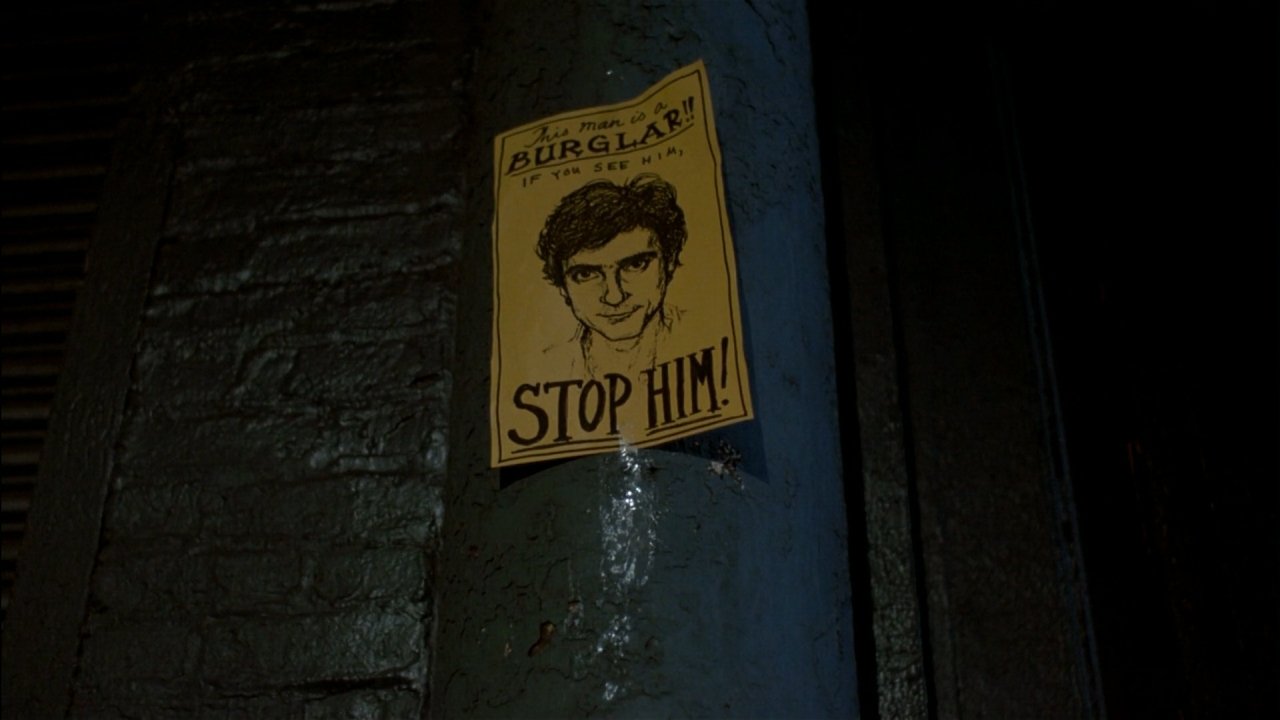

Our guide through this urban nightmare is Paul Hackett, played with masterful everyman exasperation by Griffin Dunne. Paul is a word processor, bored with his routine, who makes a spontaneous decision to visit Marcy (Rosanna Arquette, captivatingly flighty and mysterious) after a chance meeting in a coffee shop. He ventures downtown to SoHo, a neighborhood depicted here as an almost mythical realm operating under its own bizarre logic after midnight. What follows isn't just a bad date; it's a cascade of escalating misfortunes, misunderstandings, and encounters with increasingly eccentric, sometimes menacing, characters. From sculptors obsessed with plaster (Verna Bloom) to paranoid ice cream vendors (Teri Garr) and tragically inept burglars (Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong), Paul careens from one bizarre situation to the next, his desperation mounting as the hours tick by and his funds dwindle.

Scorsese Unleashed (On a Budget)

It's fascinating to remember After Hours arrived when Martin Scorsese, arguably the preeminent American filmmaker, found himself in a career bind. His passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ, had been shut down amidst controversy, leaving him searching for something smaller, quicker, something he could simply make. He found it in Joseph Minion's sharp, unsettling script (originally titled "Lies" and written while Minion was a student at Columbia Film School). Working with a relatively modest budget of around $4.5 million – pocket change compared to his usual epics – Scorsese poured all his cinematic energy into this contained pressure cooker. The result is pure directorial virtuosity.

Collaborating with cinematographer Michael Ballhaus (who would lens several more Scorsese pictures, including Goodfellas), Scorsese crafts a visually distinct New York night. The camera feels jittery, nervous, mirroring Paul's escalating panic. Tight close-ups trap us with Dunne, while wider shots emphasize the desolate, rain-slicked streets, lit by pools of neon and harsh streetlights. SoHo becomes a character itself – alluring from afar, but treacherous up close. Michael Kamen's score pulses with an anxious energy that perfectly complements the visuals, ratcheting up the tension without ever becoming overbearing. It's a testament to Scorsese's skill that he could take this smaller project and imbue it with such kinetic style, ultimately winning him the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival. It wasn't a smash hit initially, only grossing about $10.6 million in the US, but its reputation has rightly grown over the years, cementing its place as a bona fide cult classic.

The Man Who Fell to SoHo

At the heart of the film's success is Griffin Dunne. His performance is a tightrope walk between comedy and terror. Paul isn't a hero; he's just a guy trying to get home. Dunne makes his mounting frustration, disbelief, and sheer panic utterly believable. We feel every slight, every accusation, every slammed door. He’s the relatable anchor in a sea of absurdity. The supporting cast is a murderer's row of fantastic character actors, each leaving a memorable impression: Rosanna Arquette's enigmatic Marcy sets the strange tone early on, Verna Bloom is unforgettable as the lonely sculptor June, Teri Garr brings manic energy as Julie, Catherine O'Hara pops up as a vengeful Mister Softee vendor, and John Heard provides a brief moment of seeming normalcy as Tom the bartender, before that too dissolves. Even Cheech & Chong's appearance feels less like a typical stoner comedy bit and more like another layer of the night's strange texture.

Before the Digital Escape Hatch

Rewatching After Hours today really underscores how much the world has changed. Paul's predicament is amplified by the analogue nature of 1985. There are no cell phones to call for help, no GPS to navigate, no Uber to summon a ride. His dwindling cash, the rising subway fare, the reliance on payphones and finding someone – anyone – who might offer assistance, all contribute to the feeling of utter helplessness. It captures a specific kind of urban vulnerability that feels almost quaint now, yet the core anxiety remains potent. Did you ever find yourself stranded late at night in an unfamiliar part of town back then, pockets feeling lighter than you thought? The film taps right into that primal fear. Interestingly, the film almost snagged an X rating, not for violence or overt sexuality, but for perceived homosexual undertones between Neil and Pepe (the burglars). Scorsese had to trim just a few frames to secure the R, a reminder of the sometimes baffling standards of the era.

The Lingering Anxiety

After Hours poses uncomfortable questions beneath its darkly comic surface. Is Paul simply a victim of circumstance, a Job figure suffering outrageous fortune? Or is there something in his initial yuppie entitlement, his slightly awkward interactions, that somehow invites this chaos? The film offers no easy answers. It functions as a perfectly crafted anxiety dream, a cautionary tale about stepping outside your comfort zone, and perhaps a commentary on the breakdown of connection in modern urban life. What stays with you isn't just the escalating series of bizarre events, but the feeling – that knot in your stomach as Paul realizes, yet again, that things are about to get worse.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful direction, Griffin Dunne's perfect central performance, its unique and sustained atmosphere of comic dread, and its enduring status as a standout cult classic. It’s Martin Scorsese operating with laser focus, turning budgetary constraints into stylistic strengths. The film is tight, relentless, and darkly funny, capturing a specific time and place while tapping into universal anxieties. It’s a near-perfect exercise in sustained tension and surreal humor.

After Hours remains a vital, jittery piece of 80s filmmaking, a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying monsters aren't supernatural, but the ordinary people and random misfortunes you might encounter on a single, terrible night out. It’s the kind of film that makes you profoundly grateful for your own boring bed.