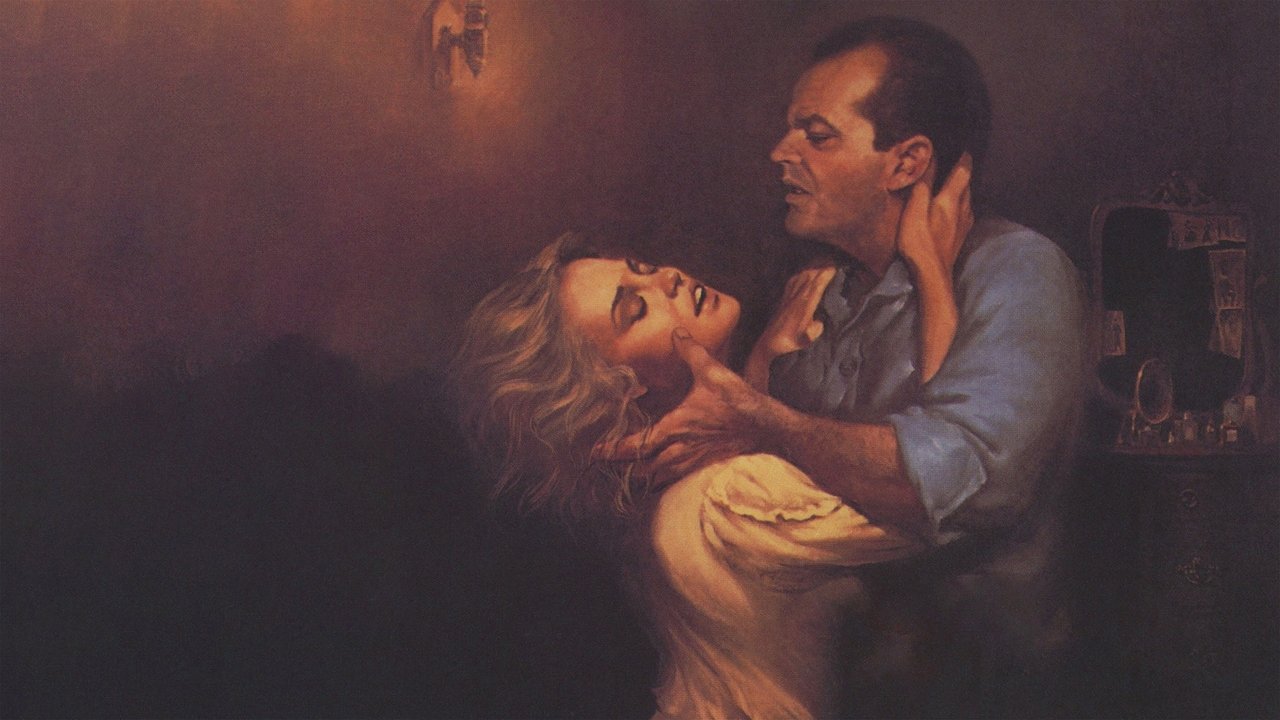

It starts with the heat, doesn't it? Not just the oppressive, sunbaked dust of the Depression-era California roadside, but the immediate, dangerous heat that sparks between Jack Nicholson's drifter, Frank Chambers, and Jessica Lange's Cora Papadakis. From the moment Frank lays eyes on Cora in that stifling roadside diner, Bob Rafelson's 1981 adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice coils around you, a simmering pot of desperation and illicit desire threatening to boil over at any second. It’s a film that feels less like a story being told and more like an atmosphere you’re forced to inhabit, thick with unspoken longing and the sour tang of bad decisions waiting to happen.

A Bleak American Dreamscape

Based on James M. Cain's famously terse 1934 novel – a cornerstone of hardboiled noir – this version arrived decades after the more constrained, but still potent, 1946 film starring Lana Turner and John Garfield. Rafelson, reteaming with Nicholson for their fourth collaboration after striking gold with films like Five Easy Pieces (1970), wasn't interested in pulling punches. Working from a screenplay by the formidable David Mamet, this Postman strips away the Hays Code gloss, plunging directly into the raw, often ugly, heart of Cain's story. The setting itself, the Twin Oaks diner owned by Cora's much older, immigrant husband Nick (John Colicos), feels less like a place of opportunity and more like a sun-bleached trap, amplifying the sense of confinement that gnaws at both Frank and Cora. You can almost taste the dust in the air, feel the sticky vinyl of the booths, sense the dead-end monotony that fuels their reckless urges.

Animal Magnetism

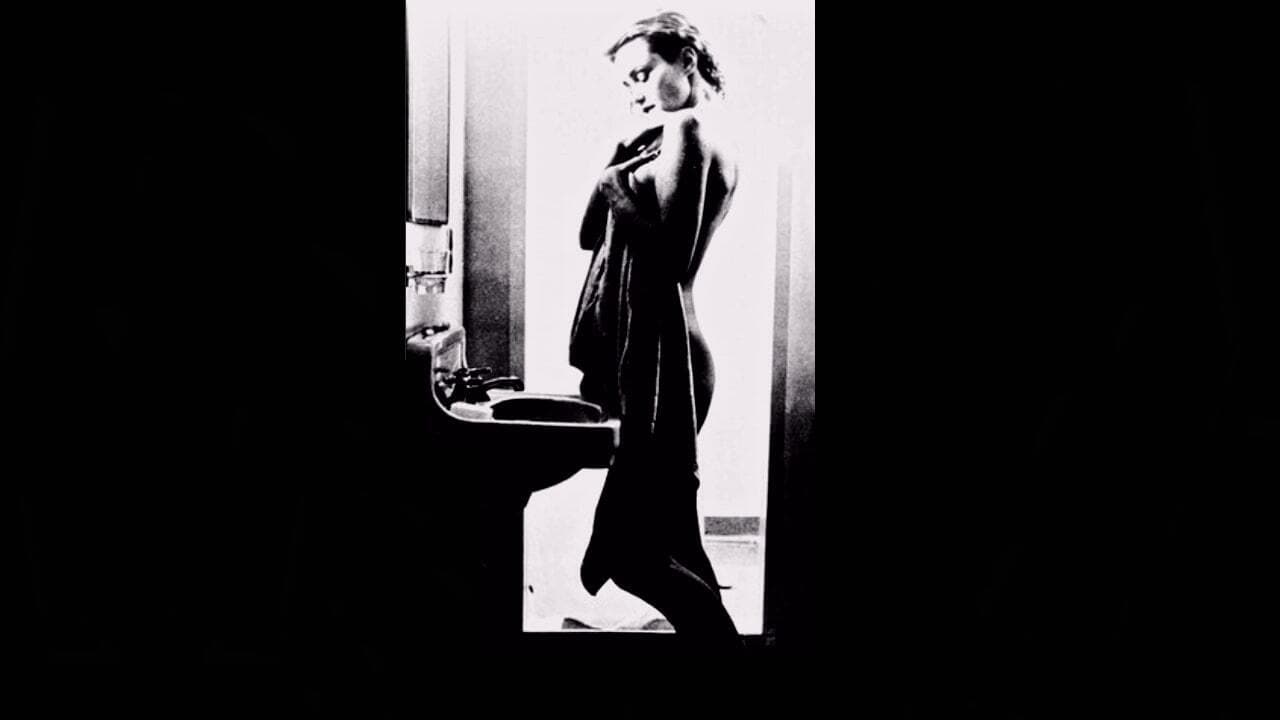

What truly ignites the film, however, is the ferocious chemistry between its leads. Nicholson, already a bona fide superstar, channels Frank's restlessness and casual amorality with unsettling ease. He’s charming and repellent in equal measure, a man running from something, or perhaps just running towards trouble. But it was Jessica Lange, in a performance that forcefully shed the ‘damsel in distress’ image from 1976's King Kong, who became the revelation. Her Cora isn't just a femme fatale; she's a complex storm of ambition, frustration, vulnerability, and simmering sensuality. Lange famously beat out formidable competition, including Meryl Streep who also auditioned, securing the role that proved her immense dramatic talent.

Their connection is immediate, physical, and almost terrifyingly primal. It culminates, of course, in that scene on the kitchen table – a moment still discussed decades later. More than just shock value (though it certainly provided that, contributing to the film's initial X rating before trims secured an R), the scene functions as a point of no return. It’s a raw, messy, almost violent expression of passion that shatters the last vestiges of restraint, sealing their doomed pact. The intensity was reportedly real on set, requiring immense trust and careful choreography between the actors and director. Does the explicitness serve the story? I think it does, grounding the noir fatalism in a tangible, almost unbearable carnality absent from the earlier adaptation.

Crafting the Claustrophobia

Rafelson, aided by the legendary cinematographer Sven Nykvist (a frequent Ingmar Bergman collaborator), masterfully uses the desolate landscapes not to convey freedom, but entrapment. The wide-open spaces feel just as confining as the diner's cramped kitchen. Mamet's script, while perhaps less overtly stylized than his later famous works, provides the lean, functional framework. The dialogue is sparse, often blunt, reflecting characters who act on impulse more than introspection. It’s the looks, the pauses, the simmering tension in the frame that truly tell the story. The production reportedly cost around $12 million, and while it wasn't a runaway box office success (grossing just over $12 million domestically), its commitment to a gritty, adult vision of Cain's novel felt significant in the landscape of early 80s cinema, pushing boundaries previously tested by films like Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977).

Echoes in the Dust

Watching it again now, perhaps on a well-worn VHS tape pulled from the back shelf, the film’s power remains undeniable. It’s a study in how desire curdles into obsession, how the pursuit of a seemingly simple goal – escape, love, money – leads down a path paved with disastrous consequences. It asks uncomfortable questions: What happens when societal constraints clash with primal urges? Is fate truly inescapable, especially for those living on the margins? The bleakness can be heavy, the characters often difficult to root for, yet their desperate struggle feels profoundly human, even in its ugliness. It perfectly captures that noir sensibility where every choice seems to lead inevitably towards doom, that sense of the postman's second, fatal knock.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's powerhouse performances, particularly Lange's star-making turn, its palpable atmosphere of heat and desperation, and its unflinching commitment to the dark, adult themes of Cain's novel. Rafelson's direction and Nykvist's cinematography create a distinct and memorable mood. While perhaps not as tightly plotted or accessible as the 1946 version for some viewers, its raw intensity and psychological depth make it a compelling, if challenging, piece of 80s neo-noir. It loses a point or two perhaps for a certain oppressive bleakness that might alienate some, but its strengths are considerable.

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981) isn't a comfortable watch, nor should it be. It lingers like the taste of cheap whiskey and regret, a potent reminder that some doors, once opened, can never truly be closed again. A fascinating, sweaty artifact from an era when mainstream cinema wasn't afraid to get its hands dirty.