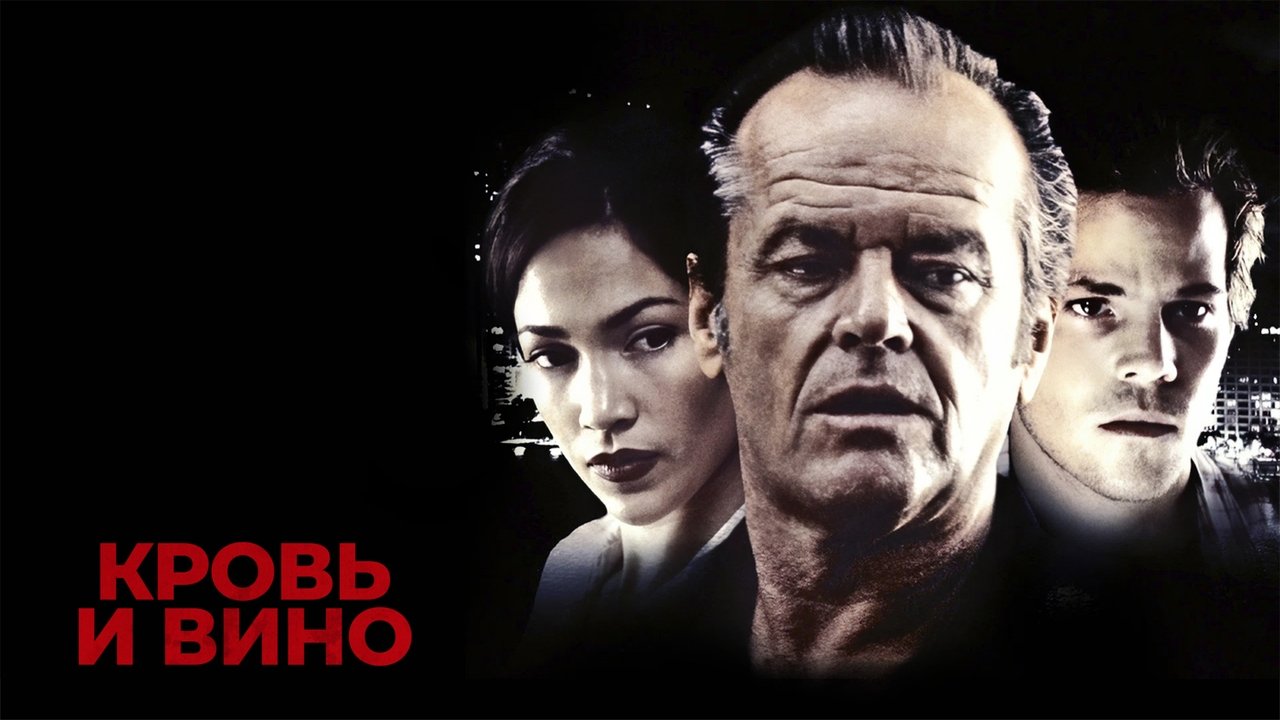

It’s a strange thing, watching giants grow older on screen. When word got out in the mid-90s that Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson were teaming up again for Blood and Wine (1996), there was a certain weight of expectation. This wasn't just another movie; it was the fourth collaboration between the director and star who had given us searing character studies like Five Easy Pieces (1970) and The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), and the heated passion of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981). What dark corners would they explore this time? The answer, simmering under the oppressive South Florida sun, turned out to be a brutally effective, if deeply uncomfortable, neo-noir portrait of greed curdling into familial rot.

Sun-Drenched Desperation

Forget the slick, high-tech heists that were becoming common currency in the 90s. Blood and Wine feels grounded, almost sweaty, baked in the inescapable humidity of Miami and the Florida Keys. Nicholson plays Alex Gates, a wine merchant whose business is failing, driving him to plan a jewel heist with a volatile, ailing safecracker named Vic (Michael Caine). The plan seems simple enough: steal a million-dollar necklace from a wealthy client's home where Alex's younger Cuban-American wife, Gabriella (Jennifer Lopez), works as a nanny. But Alex's frayed relationship with his resentful stepson, Jason (Stephen Dorff), complicates everything. Jason, already disgusted by Alex's treatment of his mother (played with weary resignation by Judy Davis), stumbles onto the stolen necklace, setting off a chain reaction of betrayal, desperation, and violence that spirals utterly out of control. The plot isn't revolutionary, perhaps, but it’s the venomous character dynamics that give the film its bite.

Fractured Family, Tarnished Gold

This is where Blood and Wine truly digs in. Nicholson, then nearing 60, isn't playing the charming rogue of his younger years, though flashes of that dangerous charisma remain. Here, it's curdled into something uglier: the entitlement of a man used to getting his way, now flailing desperately as his world collapses. He's magnetic, yes, but also deeply repellent. It’s a raw, unvarnished performance that refuses easy sympathy. Opposite him, Stephen Dorff channels a potent mix of wounded pride and simmering rage as Jason. Their confrontations crackle with genuine animosity, the long-simmering resentments of a broken family boiling over. You feel the weight of their toxic history in every venomous exchange.

Caught between them is Jennifer Lopez, in one of her more substantial early roles just before her career exploded with Selena the following year. As Gabriella, she’s more than just a damsel or a femme fatale; she's navigating a treacherous landscape, torn between loyalty, self-preservation, and perhaps a genuine, if misplaced, affection. Lopez brings a compelling blend of vulnerability and steeliness to the part, holding her own against the veteran actors. And then there’s Michael Caine. Though his screen time as Vic is relatively brief, his impact is immense. Frail, coughing, yet radiating a chilling ruthlessness, Caine delivers a masterclass in contained menace. His scenes with Nicholson are pure gold, two old lions circling each other, their partnership built on mutual necessity and utter lack of trust.

The Weight of Collaboration

Bob Rafelson directs with a kind of brutal honesty that characterized his best work. There are no flashy camera tricks, no attempts to romanticize the grubby desperation unfolding. He lets the Florida locations – the opulent houses, the cramped boat cabins, the dusty marinas – become almost another character, reflecting the moral decay. Cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel (who would later lens The Usual Suspects and Drive) captures both the seductive beauty and the stifling heat of the setting perfectly. The film feels tangible, lived-in, which only makes the betrayals sting more. Michał Lorenc's score underscores the tension without overwhelming it, letting the silences and the strained dialogue carry much of the weight.

This film marked the end of the road for the Nicholson-Rafelson partnership, a collaboration that spanned over 25 years. Perhaps fittingly, it’s their bleakest outing. It’s interesting to note that despite the pedigree, Blood and Wine wasn’t a hit. Pulling in just over $8 million against a reported $26 million budget, it seemed audiences in 1996 perhaps weren't quite ready for such an unremittingly dark tale, especially one featuring stars often associated with more crowd-pleasing fare. I recall renting the VHS, maybe expecting something closer to a standard thriller, and being struck by its grim intensity. It felt more like a throwback to the cynical crime films of the 70s than much of what was playing at the multiplex.

Final Reckoning

Blood and Wine isn't an easy watch. Its characters are deeply flawed, often despicable, and the narrative offers little in the way of redemption. Yet, there's a hypnotic quality to its downward spiral, fueled by powerhouse performances and Rafelson's unflinching direction. It’s a potent cocktail of noir fatalism and sun-baked desperation, exploring the corrosive effects of greed on already fractured relationships. If you’re looking for feel-good entertainment, look elsewhere. But if you appreciate character-driven thrillers that aren't afraid to stare into the abyss, this one delivers a bitter, memorable vintage.

Rating: 7.5 / 10

Justification: The rating reflects the film's undeniable strengths in acting (Nicholson, Caine, Dorff, Lopez are all excellent), atmosphere, and Rafelson's confident, mature direction. The narrative is tight and compellingly bleak. It loses a couple of points perhaps for its relentless grimness, which might alienate some viewers, and a plot that, while effective, doesn't break entirely new ground in the noir genre. However, its unflinching portrayal of human weakness and the sheer talent involved make it a significant, if perhaps overlooked, entry from the mid-90s crime catalogue.

Final Thought: It lingers, this one – less like a fine wine, perhaps more like the bitter dregs, reminding you how quickly family ties can unravel when soaked in avarice and resentment. A potent, uncomfortable pour from the Rafelson/Nicholson cellar.