It starts not with a bang, but with a brutal, ugly fumble in a Manchester back alley, immediately setting a tone that refuses to flinch. Then comes the flight, the escape to London, and we meet Johnny. And truly, meeting Johnny, embodied with terrifying magnetism by David Thewlis, is the jagged heart of Mike Leigh’s unforgettable 1993 film, Naked. This isn’t a movie you casually put on; it’s one you brace for, one that burrows under your skin and stays there, long after the fuzzy tracking lines of the VHS tape gave way to static.

A Monologue in the Dark

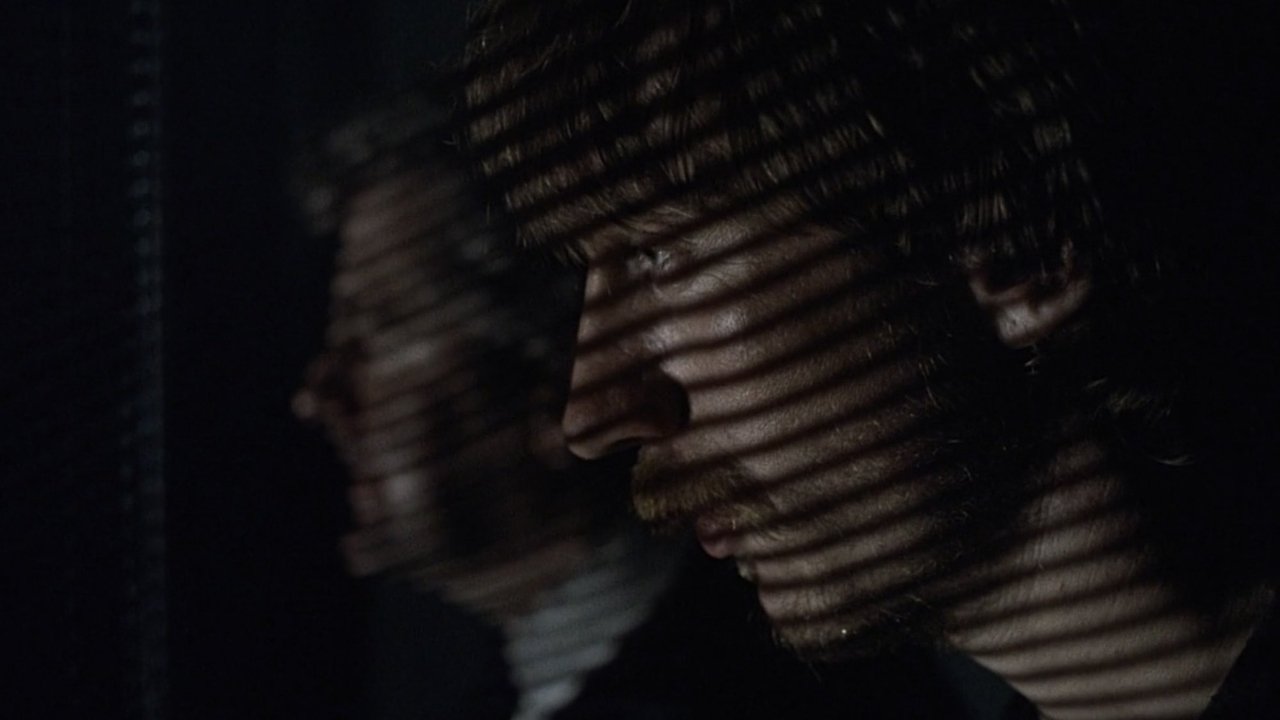

What defines Naked? Is it the narrative, a loose, episodic journey through London's nocturnal underbelly? Or is it the character of Johnny himself – a highly intelligent, deeply wounded, relentlessly verbose nihilist who drifts from encounter to encounter, leaving a trail of bruised psyches (and sometimes bodies) in his wake? For me, it's undeniably the latter, fuelled by one of the most ferocious performances of the 90s. David Thewlis isn’t just acting; he’s channeling something raw and unsettling. His Johnny is a whirlwind of contradictions: articulate yet cruel, insightful yet self-destructive, magnetic yet repulsive. His torrential monologues – philosophical diatribes touching on everything from cosmology to conspiracy theories – are both captivating and exhausting. You lean in, mesmerized by the intellect, only to recoil from the venom. It’s a performance that rightly stunned Cannes, earning Thewlis the Best Actor award alongside Mike Leigh's Best Director prize.

Leigh's Improvised Reality

Understanding Mike Leigh's unique filmmaking process is key to appreciating Naked's unsettling power. Known for his extensive use of improvisation (Secrets & Lies, Life is Sweet), Leigh worked with his actors for months to develop their characters and backstories before a single frame was shot. There wasn't a conventional script in the way most productions have one. Instead, the dialogue and interactions emerged organically from this deep preparatory work. This method imbues the film with a startling, often uncomfortable, sense of realism. The conversations feel less like scripted exchanges and more like overheard fragments of desperate lives. Reportedly, Thewlis spent considerable time walking the streets, observing, and absorbing the rhythms and language that would become Johnny’s own, building the character from the inside out. This dedication bleeds onto the screen, making Johnny feel less like a fictional construct and more like a force of nature Leigh managed to capture on film.

London After Midnight

The film's atmosphere is thick with a specific kind of urban decay – the pre-millennial tension of a London grappling with the hangover of Thatcherism. Cinematographer Dick Pope paints the city in bruised blues and sickly yellows, a landscape of grimy flats, desolate streets, and transient encounters. It’s a London stripped of glamour, reflecting the internal emptiness of its inhabitants. The relentless night deepens the sense of alienation, trapping Johnny and those he encounters (like his exasperated ex, Louise, played with weary strength by Lesley Sharp, or the tragically vulnerable Sophie, a heartbreaking Katrin Cartlidge) in a purgatorial limbo. There’s a feeling of profound disconnection, of people talking at each other rather than to each other, circling the same existential drain.

A Challenging Artifact

Let’s be honest, Naked is not an easy watch. Its depiction of misogyny is stark and often disturbing, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about exploitation and power dynamics. Johnny’s verbal and sometimes physical assaults can feel relentless. Is the film endorsing his worldview? I don't believe so. Leigh presents Johnny, warts and all, as a symptom of a deeper societal malaise, a damaged soul lashing out at a world he perceives as equally broken. It doesn’t ask us to like Johnny, merely to witness him, to grapple with the uncomfortable questions his existence raises. What happens when intelligence curdles into cynicism? How does societal neglect breed monsters? Watching it again, decades after first sliding that tape into the VCR – a tape that probably didn't see as much rental action as, say, Jurassic Park released the same year – its power to provoke remains undimmed. Its low budget (reportedly around £1 million) feels irrelevant; the richness comes from the performances and the unflinching gaze.

Why It Lingers

Naked represents a certain kind of uncompromising 90s British cinema – raw, confrontational, and deeply intelligent. It's a film that trusts its audience to engage with difficult material without easy answers or neat resolutions. The supporting cast is uniformly excellent, each providing a brief, memorable counterpoint to Johnny's vortex of negativity. But ultimately, it's Thewlis's film. His performance is a tightrope walk without a net, utterly fearless and unforgettable. It launched him into international recognition, leading to roles vastly different but always showcasing that fierce intelligence (think Remus Lupin in the Harry Potter series or Sir Patrick Morgan in Wonder Woman).

***

Rating: 9/10

The justification for this high score rests almost entirely on the film's audacious artistic vision, Mike Leigh's masterful direction, and David Thewlis's towering, benchmark performance. It's a difficult, demanding film, and its bleakness and confrontational subject matter won't be for everyone. However, its raw power, psychological depth, and unforgettable central character make it a landmark of 90s cinema. It’s filmmaking that challenges, provokes, and refuses easy categorization – the kind of discovery that made browsing those video store aisles sometimes feel like an act of profound exploration.

Naked doesn't offer comfort, but it demands attention, leaving you pondering the darkness lurking not just on the fringes of society, but potentially within us all. What piece of Johnny's bleak philosophy, if any, resonates unsettlingly true even today?