Dust motes dance in the sliver of light piercing the ancient gloom. A silence centuries deep is about to be shattered, not just by shovels, but by an ambition bordering on the profane. This isn't just another dig; it's the unearthing of Bram Stoker's other terrifying tale, The Jewel of Seven Stars, brought to the screen as The Awakening (1980). And behind the scenes, another kind of darkness brewed – the legendary British scribe Nigel Kneale (Quatermass) delivered a script, only to later demand his name be removed, deeply dissatisfied with the final product. That shadow hangs over the film, a "what if" that adds another layer to its already considerable sense of unease.

An Obsession Born in the Sand

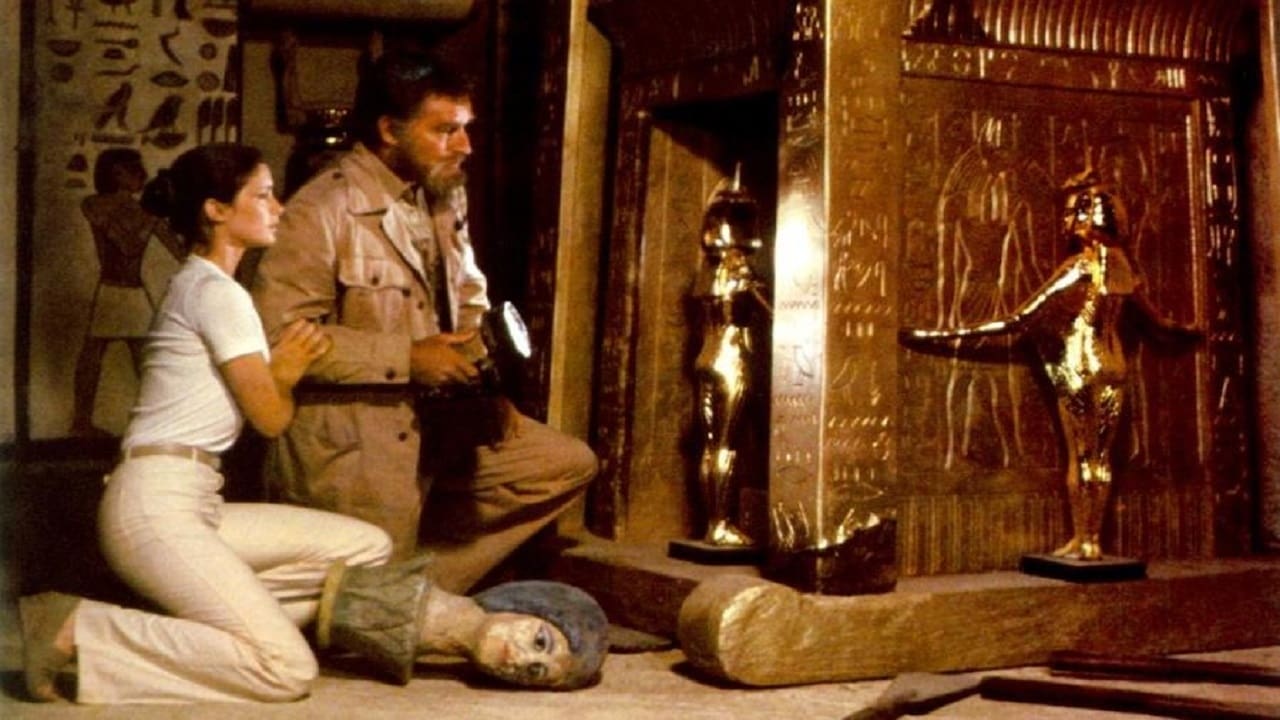

The film centers on Matthew Corbeck, played by the imposing Charlton Heston, an actor synonymous with epics like Ben-Hur (1959) and The Ten Commandments (1956), making his presence here feel both commanding and slightly jarring. Corbeck is an archaeologist consumed by a singular goal: finding the untouched tomb of Queen Kara, a figure of mythic malevolence. He finds it, alright, violating the sacred space at the exact moment his wife (played by Jill Townsend) gives birth back in London. His daughter, Margaret, arrives stillborn, only to gasp back to life as Corbeck reads Kara's hieroglyphs aloud. Coincidence? In a film steeped in Egyptian curses, you know better. This setup, filmed partly on location amidst the staggering grandeur of Egypt, immediately establishes a weighty, almost suffocating atmosphere. You can practically feel the dry heat and the crushing weight of millennia pressing down. The decision to shoot in genuine locations adds an authenticity that studio sets, even the meticulous ones constructed at Pinewood Studios in England for other scenes, can't fully replicate.

The Slow Creep of Dread

Eighteen years later, Margaret (now played by Stephanie Zimbalist) is nearing her birthday, and Corbeck, still obsessed, prepares to unveil Kara's mummy to the world. But the spirit of Kara, it seems, has plans of its own, using Margaret as its vessel. What unfolds is less a traditional monster movie and more a slow-burn psychological horror. Director Mike Newell, who would later helm vastly different fare like Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005), focuses on building tension through atmosphere rather than jump scares. The dread accumulates gradually – strange occurrences, Margaret's unsettling shifts in personality, and the palpable sense of an ancient, malevolent intelligence pulling the strings. Susannah York, as Corbeck's now estranged second wife Jane, brings a grounded sense of growing alarm, acting as the audience's anchor amidst the encroaching weirdness. Her performance provides a necessary emotional counterpoint to Heston's often stoic, single-minded portrayal of Corbeck.

Atmosphere Over Action

The Awakening lives and breathes its atmosphere. The cinematography often favors shadows and claustrophobic framing, enhancing the psychological tension. The score, by Claude Bolling, contributes effectively, underpinning key scenes with a sense of impending doom rather than overt orchestral shrieking. While perhaps not boasting the groundbreaking practical effects of some contemporaries, the film has its moments. The design of Queen Kara's mummy is suitably withered and unsettling, and certain sequences – particularly those involving Kara's psychic influence – possess a genuine creepiness that lingers. It's the kind of horror that aimed for under-the-skin discomfort, a feeling amplified, perhaps, by watching it on a slightly fuzzy VHS tape late at night, the static hiss merging with the film's own ambient dread. Doesn't that final sequence, even now, retain a certain chilling power?

Heston and the Curse of Kneale

Seeing Charlton Heston in this kind of role was certainly a draw back in the day. He brings his undeniable screen presence, but his character is often difficult – arrogant, neglectful, driven by an obsession that borders on madness. It’s a performance that fits the character's destructive single-mindedness, even if it doesn't always invite audience sympathy. The shadow of Nigel Kneale's dissatisfaction looms large, however. Knowing his original vision was altered (reportedly softened and made more conventional) leaves one wondering about the sharper, potentially bleaker film that might have been. Kneale was a master of intellectual horror and creeping paranoia; whispers suggest his script was perhaps too complex or downbeat for the studio, leading to the rewrites he abhorred. This troubled production history is woven into the fabric of the film itself, contributing to its melancholic, slightly "off" feeling. The film reportedly cost around $5 million but only managed to gross about $11 million worldwide, suggesting audiences at the time perhaps weren't quite sure what to make of this stately, atmospheric Stoker adaptation compared to more visceral horror offerings.

Unearthed Legacy

Compared to Hammer's earlier, more lurid take on the same Stoker novel, Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (1971), The Awakening feels positively restrained, aiming for a different kind of chill. It lacks the iconic status of Universal's classic The Mummy (1932) or the adventurous thrills of the later Stephen Sommers reboot series starring Brendan Fraser. Instead, it occupies a quieter, moodier space in the mummy subgenre. It’s a film more about the violation of the past and the inescapable grip of ancient power than about a bandaged monster chasing victims down corridors.

Rating: 6/10

The Awakening is a film easier to admire for its potent atmosphere and pedigree than to outright love. Its deliberate pace can test patience, and Heston's chilly protagonist keeps the viewer at arm's length. Yet, the direction crafts moments of genuine unease, the Egyptian locations lend authenticity, and the core Stoker/Kneale concept remains intriguing, even in its compromised form. It doesn't fully deliver on its potential, hampered perhaps by those behind-the-scenes struggles and a desire to fit a potentially challenging story into a more palatable mould.

Still, for fans of early 80s horror who appreciate a slow burn and a thick sense of doom, The Awakening offers a distinct and often unsettling viewing experience. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying curses aren't unleashed with a roar, but seep quietly into the present, carried on the dust of disturbed tombs. It remains a fascinating, flawed artifact from the VHS era – a moody testament to obsession and the things best left buried.