Okay, let's dim the lights, maybe pour something strong, and settle in. Tonight, we're pulling a tape from the shelf that might not scream blockbuster, but trust me, it resonates long after the static hits. We're talking about Henri Verneuil's chilling 1979 French political thriller, I... For Icarus (I... comme Icare). This isn't your typical car-chase, explosion-filled fare; it's something colder, more methodical, and deeply unsettling in its exploration of power, truth, and the terrifying ease with which individuals can bend to authority.

### The Echo of a Gunshot

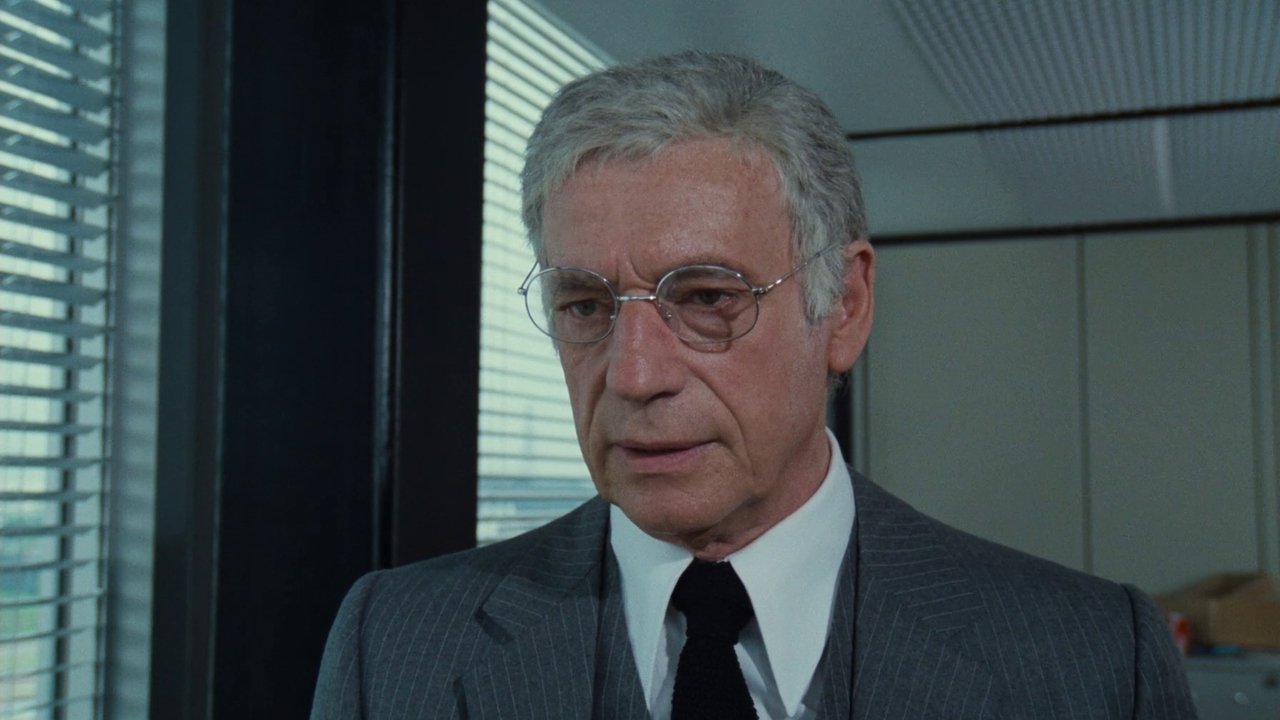

The film opens with an event chillingly familiar to anyone who remembers the grainy Zapruder footage: the assassination of a president, Marc Jarry, in a motorcade. A lone gunman is quickly identified and killed, the case seemingly closed by an official commission. But one member, Prosecutor Henri Volney, played with quiet, weary determination by the legendary Yves Montand, refuses to sign off. He senses inconsistencies, loose threads, the faint but undeniable scent of a cover-up. What unfolds is Volney's solitary, meticulous reinvestigation, a descent into a labyrinth of manipulated evidence, silenced witnesses, and shadowy forces operating just beyond the reach of accountability. Set in a fictional Western state, the parallels to real-world political assassinations, particularly JFK's, are impossible to ignore and lend the film an immediate, uncomfortable weight.

### The Investigator's Burden

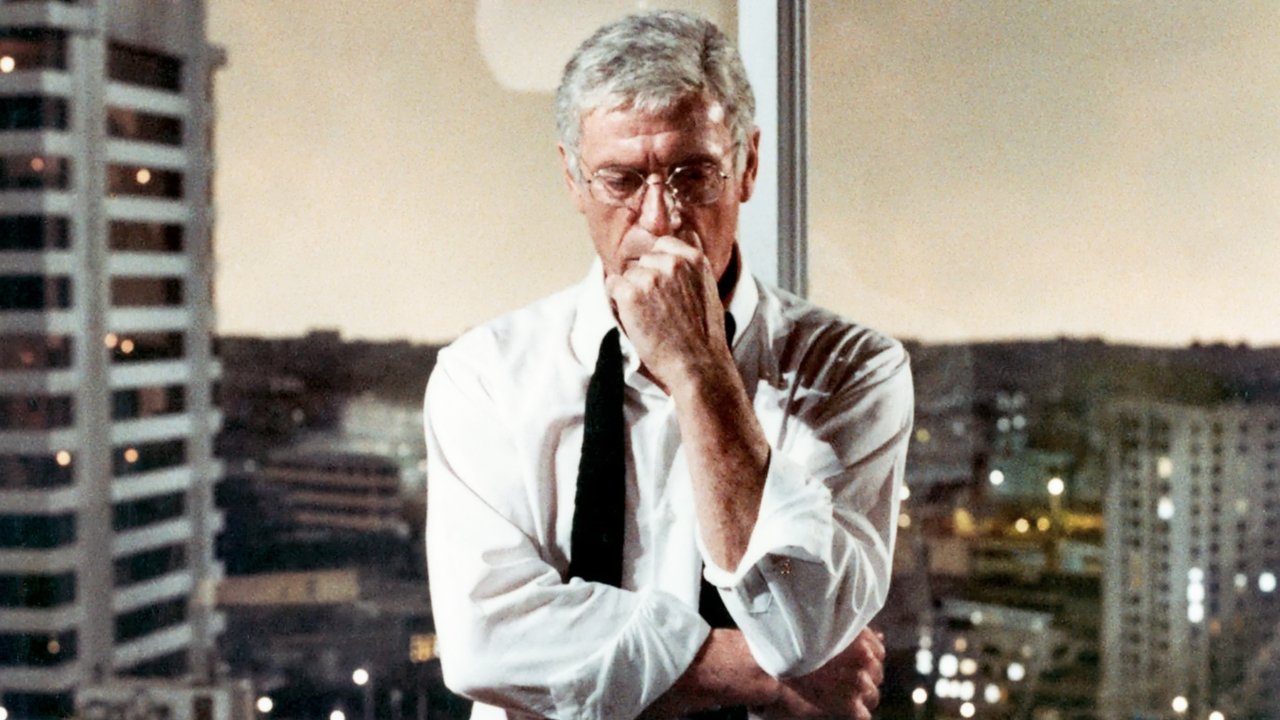

Much of the film's power rests on Yves Montand's shoulders. Known for powerful roles in films like The Wages of Fear (1953) and Costa-Gavras's political thriller Z (1969), Montand embodies Volney not as a crusading hero, but as a man burdened by conscience. He’s methodical, almost detached at times, his face etched with the exhaustion of swimming against a powerful tide. There's no swagger here, just the grim persistence of someone who simply must know the truth, regardless of the personal cost. We watch him pore over surveillance footage, cross-reference timelines, and conduct interviews that often lead to dead ends or worse. His performance is a masterclass in conveying internal struggle through stillness and subtle expression. You feel the isolation, the growing paranoia, the dawning realisation of the sheer scale of the conspiracy he's confronting.

### The Milgram Experiment: A Chilling Interlude

One of the film's most striking and unforgettable sequences involves Volney discovering evidence linked to the infamous Milgram experiment on obedience to authority. Henri Verneuil, who also co-wrote the script with Didier Decoin, doesn't just reference Stanley Milgram's controversial 1960s study; he recreates a version of it within the narrative. Volney watches recordings of seemingly ordinary people administering increasingly severe (though simulated) electric shocks to an unseen victim, simply because a figure in a lab coat tells them to continue. This isn't just a piece of shocking trivia woven in; it's the thematic core of the film laid bare. It asks the terrifying question: how easily can individuals be coerced into complicity? How thin is the veneer of morality when faced with perceived authority? Seeing this played out, even within the context of the film's fiction, is profoundly disturbing and forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about human nature – truths that directly inform the conspiracy Volney is unravelling. Who were the trigger-pullers, the planners, the silent partners, and why did they obey?

### Cold Precision and Gathering Dread

Verneuil directs with a cool, almost clinical precision that mirrors Volney's investigation. The cinematography often employs stark compositions and muted colours, emphasizing the institutional coldness of the corridors of power where the conspiracy festers. There are no flashy action sequences; the tension builds slowly, methodically, through accumulating details and the palpable sense of unseen danger closing in on Volney. Adding immeasurably to the atmosphere is the score by the incomparable Ennio Morricone. His music here isn't the soaring majesty of his Westerns, but rather a tense, often minimalist score that underscores the paranoia and the investigator's isolation, tightening the knot of dread with each revelation. Some might find the pacing deliberate, especially compared to modern thrillers, but it's this very deliberateness that allows the weight of the situation, and the implications of Volney’s discoveries, to fully sink in. It’s a film that demands patience and rewards it with profound unease.

### Why Icarus?

The title itself, I... For Icarus, hints at the inevitable tragedy. Like the mythical figure who flew too close to the sun, is Volney doomed by his pursuit of truth? The film doesn't offer easy answers or triumphant conclusions. It exists in the grey zone of political reality, where power protects itself, and the individual seeking to expose it faces overwhelming odds. Its legacy lies in its unflinching portrayal of systemic corruption and its chilling reminder, amplified by the Milgram sequence, of the psychological mechanisms that enable such systems to persist. It stands proudly alongside other great paranoid thrillers of the 70s like The Conversation (1974) and All the President's Men (1976), though perhaps with a bleaker, more European sensibility. Finding this on VHS back in the day, perhaps nestled between more conventional thrillers, felt like uncovering a secret – a smart, sobering film that stayed with you.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: I... For Icarus is a masterfully crafted political thriller, anchored by a superb, understated performance from Yves Montand. Its intelligent script, chilling incorporation of the Milgram experiment, and palpable atmosphere of paranoia make it a standout. The deliberate pacing enhances the dread rather than detracting, though it might test the patience of some viewers expecting faster action. The score by Ennio Morricone is perfectly attuned to the film's mood. It loses a point perhaps for its bleakness feeling almost overwhelming at times, and maybe a touch more character depth beyond Volney could have enriched it further, but its core message and execution are incredibly strong.

Final Thought: This is a film that doesn't just entertain; it probes, questions, and leaves you contemplating the often-uncomfortable relationship between power, truth, and individual conscience long after the tape runs out. Who truly holds the strings, and what price is paid for trying to see them?