The flickering gaslight of cinematic history casts long, distorted shadows, and within one lurks a disturbing question: What if the actor playing cinema's first great vampire... wasn't acting? That chilling 'what if' is the black heart of E. Elias Merhige's Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a film that arrived just as the VHS era was fading but feels spiritually bound to those late-night rentals that left you checking the locks. It’s a film that imagines the troubled 1921 production of F.W. Murnau's silent masterpiece Nosferatu not just as difficult, but as damned.

A Pact Sealed in Darkness

The premise alone sends a shiver down the spine. John Malkovich, radiating obsessive artistic fervor, plays the visionary German director F.W. Murnau. Desperate to create the ultimate horror film, he hires the elusive and utterly bizarre stage actor Max Schreck (Willem Dafoe) to embody Count Orlok. Murnau promises his financiers and increasingly unnerved crew that Schreck is merely a devoted disciple of Stanislavski's "Method," hence his refusal to break character, his nocturnal habits, and his frankly ghastly appearance. But Murnau knows the horrifying truth: he has sourced his star directly from the Carpathian mountains, striking a Faustian bargain with a genuine creature of the night. The price for authenticity? The blood of his leading lady, Greta Schröder (Catherine McCormack), upon completion of the final scene.

The Method in the Madness

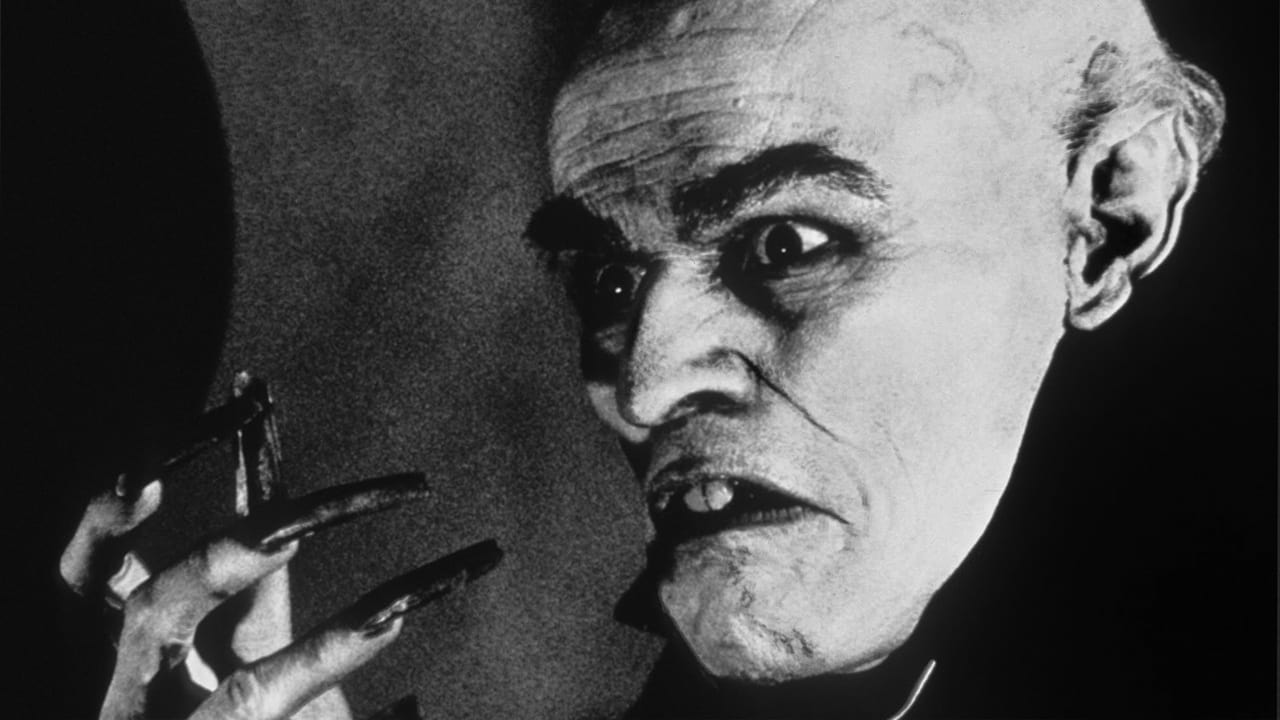

Willem Dafoe's transformation into Schreck is the stuff of nightmares, an unsettling blend of the historical actor and the fictional monster he portrays. It's a performance that earned him a well-deserved Oscar nomination, built on unsettling physicality – the hunched posture, the long, predatory fingernails, the eyes that seem ancient and hungry. The makeup is superb, referencing the iconic Nosferatu look while adding layers of decay and otherness. Legend has it Dafoe embraced the role with unnerving commitment, remaining largely in character on set, keeping his distance from the other actors (Udo Kier and Cary Elwes among the increasingly terrified ensemble) and reportedly spending hours in makeup, intensifying the illusion that something truly unnatural was stalking the production. Doesn't that dedication, bordering on possession, feel chillingly plausible within the film's world?

Director E. Elias Merhige, previously known for the deeply disturbing experimental film Begotten (1989), crafts an atmosphere thick with encroaching dread. Shot primarily in Luxembourg, the film uses mist-shrouded castles and claustrophobic interiors to mirror the decaying grandeur and isolation of Murnau's original vision. The cinematography often mimics the expressionistic style of silent film, while the score subtly underscores the mounting tension. It's less about jump scares and more about a pervasive sense of wrongness, the growing realization among the crew that their director's obsession has invited something truly malevolent into their midst.

Art at Any Cost?

Beyond the creature feature elements, Shadow of the Vampire sinks its teeth into the nature of filmmaking itself. Malkovich's Murnau is a fascinating monster in his own right – an auteur willing to sacrifice anything, and anyone, for his art. He manipulates, lies, and ultimately endangers his entire crew, driven by a vision that eclipses basic humanity. The film becomes a dark meta-commentary on the power dynamics of a film set, the blurred line between performance and reality, and the potentially vampiric nature of artistic creation – feeding off life to create an illusion. Steven Katz's script cleverly weaves historical details about the Nosferatu production (like the unauthorized adaptation of Stoker's Dracula, which nearly led to all prints being destroyed) with its central terrifying conceit. It’s a cinephile's nightmare, imagining the secrets hidden behind the flickering frames of a classic.

A Minor Legend in the Making

While perhaps not a household name like the blockbusters lining the video store shelves back in the day, Shadow of the Vampire quickly gained a cult following. Produced by Nicolas Cage (who initially considered playing Schreck himself before Dafoe was cast – can you imagine?), the film felt like a discovery, something special unearthed from the darker corners of cinema. Its modest $8 million budget was channeled effectively into atmosphere and performance, resulting in a film far more memorable than many bigger-budget horror flicks of the time. It captures that delicious thrill of finding a truly unique, slightly twisted gem. I remember seeing this on DVD shortly after its release, feeling that same dark pull I got from renting strange, atmospheric horror tapes years earlier – the sense that I’d stumbled onto something genuinely unnerving and brilliantly conceived.

Final Verdict

Shadow of the Vampire is a masterclass in atmosphere and performance, anchored by Willem Dafoe's unforgettable turn as Max Schreck/Orlok. It's a chilling fictionalization that respects its source material while spinning a terrifying new myth around it. The meta-commentary on filmmaking adds intellectual heft to the Gothic horror, creating a film that lingers long after the credits roll. While the central performances and premise are incredibly strong, perhaps some of the supporting characters feel a touch underdeveloped, slightly overshadowed by the two magnetic leads. But this is a minor quibble in a film that so successfully conjures dread.

Rating: 8.5/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's brilliant central concept, Dafoe's truly iconic performance, Malkovich's compelling portrayal of obsession, and the masterful, dread-soaked atmosphere. It's a near-perfect execution of a unique idea, docked only slightly for minor narrative threads that don't quite reach the same heights.

Shadow of the Vampire remains a potent piece of meta-horror, a dark love letter to cinema's power to create monsters, both on screen and behind the camera. It’s the kind of film that makes you look at Nosferatu – and perhaps the very act of filmmaking – with a newfound sense of unease. A chilling modern classic with deep roots in cinema's dark past.