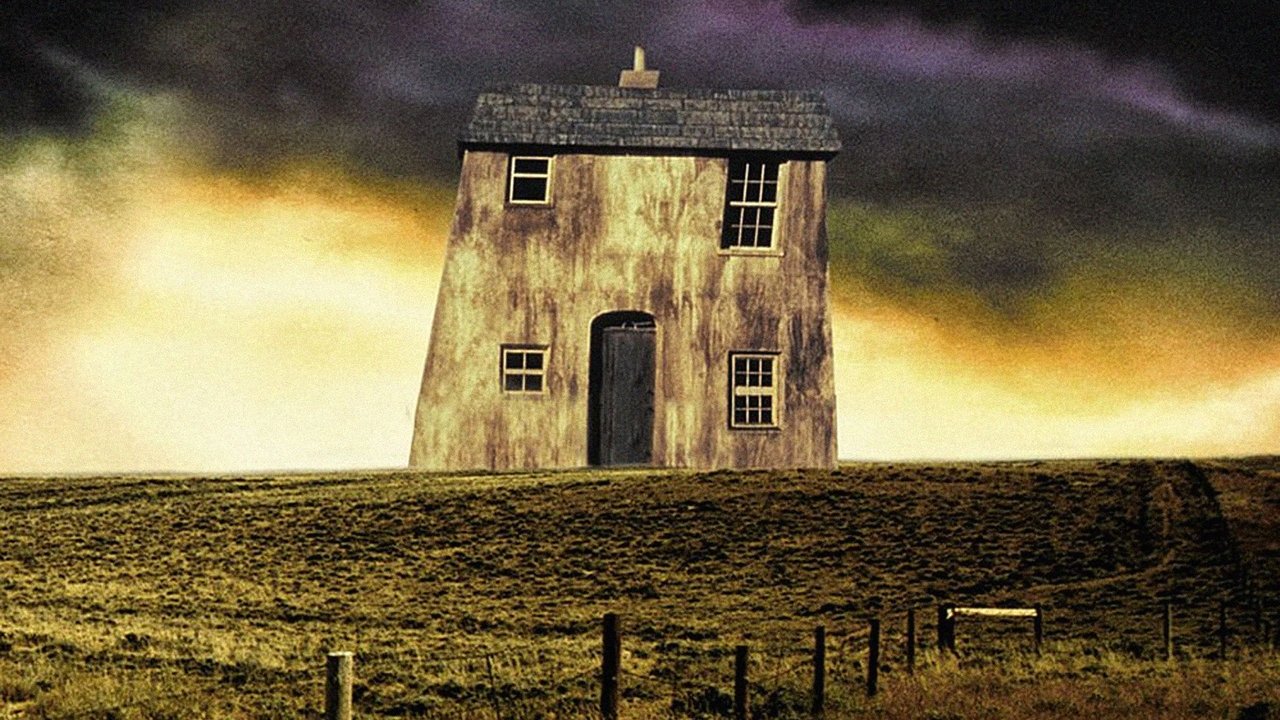

It begins with a child’s drawing, simple lines on paper sketching a lonely house on a hill. But in Bernard Rose’s Paperhouse (1988), that innocent act of creation becomes a terrifying portal, blurring the lines between a fevered imagination and a tangible nightmare. This isn't the stuff of fairy tales; it’s the cold sweat dread of a childhood illness, where the shadows lengthen and the familiar twists into the monstrous. Forget jump scares; this is a film that seeps under your skin, leaving a chill that lingers long after the credits roll, much like those strange, unsettling films we sometimes stumbled upon in the back aisles of the video store.

Where Dreams Curdle

Young Anna (Charlotte Burke, in a remarkably mature debut) is ill, confined to her bed with glandular fever. Bored and isolated, she draws a house. That night, she dreams herself inside the stark, unsettling structure she created. It’s empty, silent, mirroring the desolation she feels. Seeking companionship, she draws a face at the window – and in her next dream, finds Marc (Elliott Spiers), a boy seemingly trapped within the house's confines, unable to walk. Anna discovers she can alter this dream world with her drawings, adding details, attempting to help Marc. But her control is fragile, her subconscious fears bleeding onto the page. When frustrated, she scribbles a furious representation of her absent father (Ben Cross), she unwittingly unleashes a blind, terrifying figure into her fragile paper world, a manifestation of anger and fear given terrifying form.

The atmosphere Rose crafts is exceptional, aided immeasurably by Hans Zimmer’s early, haunting score. Long before his blockbuster dominance, Zimmer demonstrated a keen ability to evoke ethereal beauty laced with profound menace. The visuals lean into a stark, almost minimalist dread. The dream world isn't fantastical in a whimsical way; it's desolate, rendered in unnerving blues and greys, mirroring the sterile environment of illness and the bleakness of Anna’s emotional state. The house itself, simplistic yet imposing, becomes a character – a prison born of loneliness.

Faces in the Window

Charlotte Burke carries the film with astonishing poise for a young actress. Her Anna is petulant, imaginative, vulnerable, and fiercely determined. We experience the unfolding horror through her wide, increasingly terrified eyes. Opposite her, Elliott Spiers as Marc is heartbreakingly fragile. His performance is imbued with a quiet sadness that resonates deeply, a sense of resignation mixed with a desperate hope sparked by Anna's arrival. Tragically, this resonance carries a real-world echo; Spiers was battling illness during the filming period and passed away young, lending his portrayal an unintended, poignant weight. Glenne Headly also provides a grounding presence as Anna’s concerned mother, representing the waking world Anna drifts further away from.

The film’s power lies in its understanding of childhood fears – not monsters under the bed, but the more profound anxieties of isolation, helplessness, parental anger, and the terrifying fragility of the body. It taps into that specific feeling of being sick as a kid, where reality warps and the mind conjures strange landscapes. Remember that feeling? Paperhouse weaponizes it. The horror isn't just the menacing father figure; it's the loss of control, the realization that Anna's attempts to fix things often make them terrifyingly worse.

From Page to Screen Nightmare

Interestingly, Paperhouse is adapted from a 1958 children's novel, Marianne Dreams by Catherine Storr. While the book deals with similar themes, Bernard Rose, working from a script by Matthew Jacobs, amplified the psychological horror, transforming it into something far darker and more suited for adult audiences seeking atmospheric dread. This ability to mine deep-seated anxieties would, of course, serve Rose well a few years later when he unleashed the urban legend nightmare of Candyman (1992) upon audiences. You can see the DNA of that later classic here – the focus on atmosphere over gore, the exploration of psychological states manifesting physically, the unsettling blend of the mundane and the terrifying.

The production itself leaned into its limitations. Made for a modest budget (around £2 million), the dream sequences rely more on stark design, clever lighting, and suggestion than elaborate effects, which arguably enhances their unsettling power. The slightly primitive (by today's standards) look of the dream world feels authentically like a child's drawing brought to life, retaining that uncanny, not-quite-real quality that fuels the unease. It’s a prime example of how creative vision can overcome financial constraints, something often seen in the gems unearthed during the VHS era. I distinctly remember the stark, intriguing cover art drawing me in at the local rental place, promising something... different. It certainly delivered.

Lasting Impressions

Paperhouse isn't a film you easily shake off. It bypasses cheap thrills for a more profound, existential chill. It’s a haunting exploration of the subconscious, where creativity and fear intertwine with devastating consequences. The performances, particularly from the young leads, are deeply affecting, and Bernard Rose crafts a mood piece that feels both dreamlike and disturbingly real. It might move too deliberately for some modern viewers accustomed to faster pacing, but its power lies in that slow-burn descent into a nightmare drawn by a child’s hand. Does that final, ambiguous image still send a shiver down your spine?

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Paperhouse earns its high marks for its masterful atmosphere, psychological depth, and unforgettable central performances. It perfectly captures a specific kind of dreamlike dread, leveraging its low budget into a distinct visual style. While perhaps niche, it’s a truly effective piece of filmmaking that burrows into your memory. It remains a standout example of 80s dark fantasy/psychological horror, a potent reminder that sometimes the most terrifying monsters are the ones we draw ourselves.