The flicker of fluorescent lights on laminated covers, the scent of worn plastic clamshells... Sometimes, digging through the 'World Cinema' or 'Thriller' sections of the local video store unearthed something truly unexpected. Something that wasn't explosive action or broad comedy, but a slow-burn descent into a darkness that felt chillingly intimate. François Ozon's 1999 film Criminal Lovers (Les amants criminels) was exactly that kind of tape – the one you might have rented on a whim, drawn by a stark cover or a vague, intriguing synopsis, only to find yourself locked into a narrative that spiraled far beyond its initial premise.

Teenage Wasteland, Twisted Desires

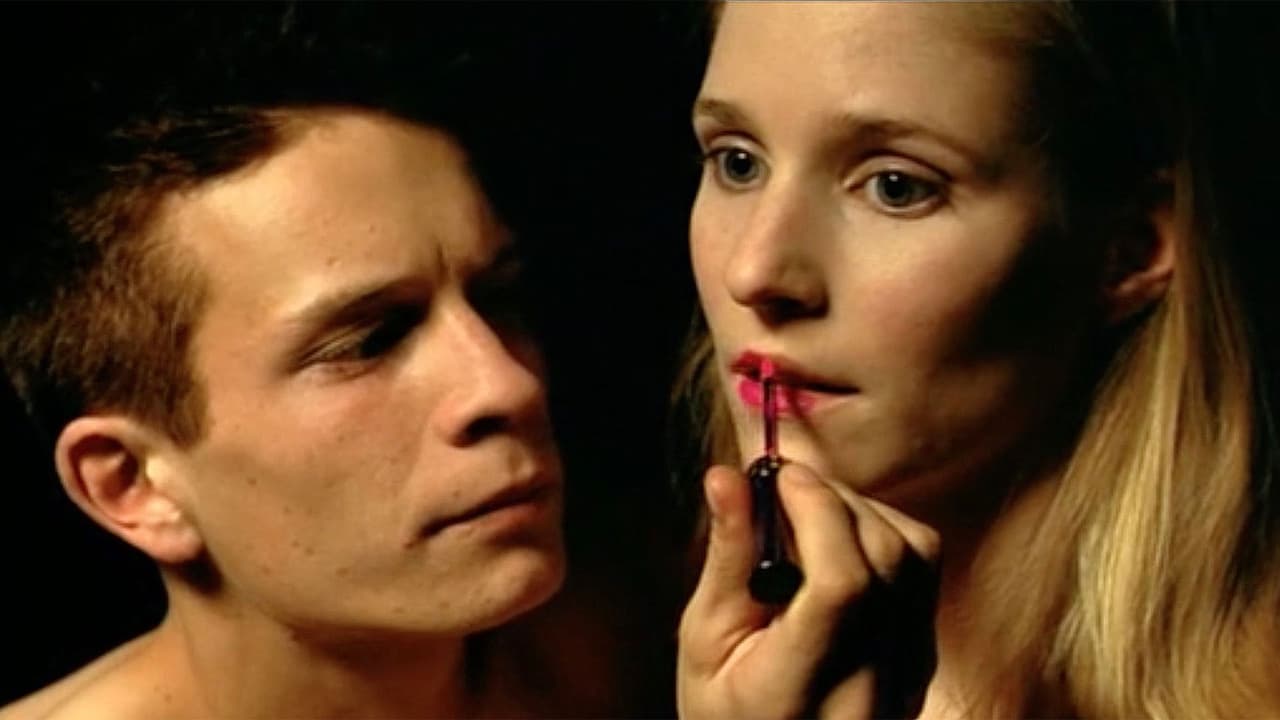

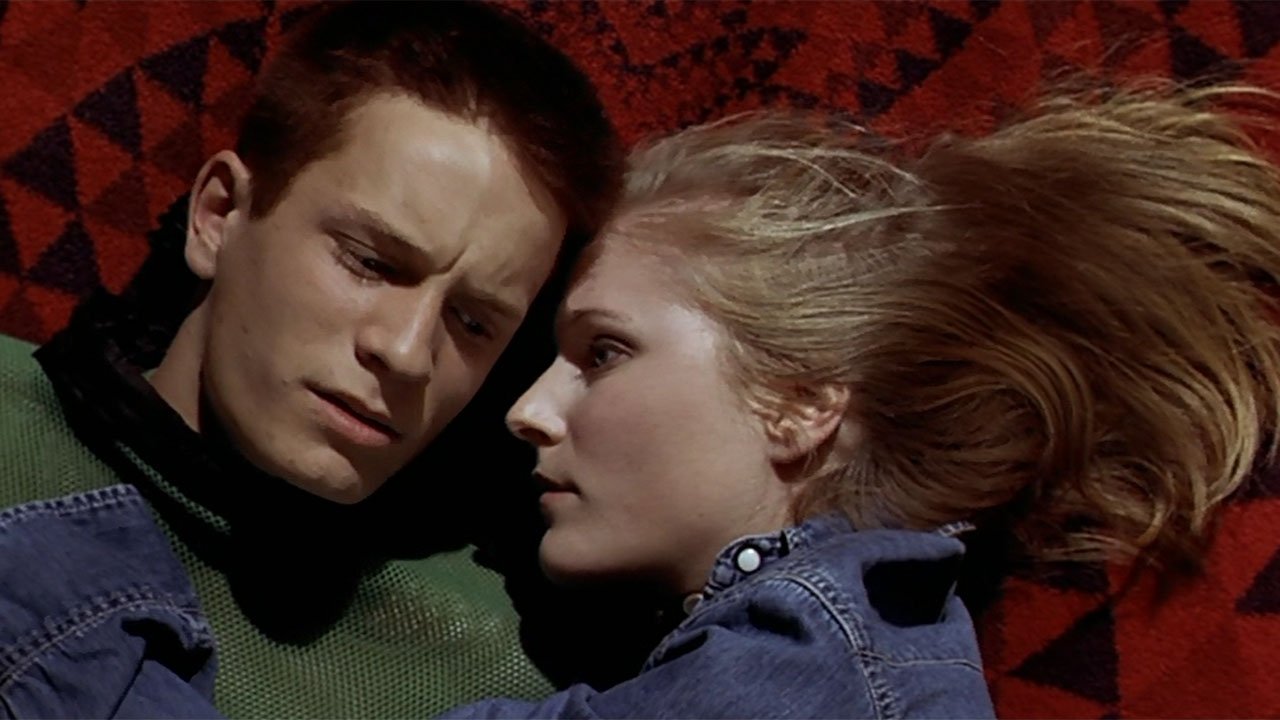

At first glance, Criminal Lovers presents a familiar scenario warped through a European art-house lens. Alice (Natacha Régnier) and Luc (Jérémie Renier, who Ozon would later cast in Potiche) are young, bored, and simmering with unfocused angst. Alice, manipulative and perhaps sociopathic, convinces the more passive Luc that their classmate Saïd is sexually assaulting her. Her proposed solution? Murder. The act itself is depicted with a cold, almost banal brutality that sets the stage – this isn't a glossy Hollywood thriller, but something far more unnerving. Ozon doesn't shy away from the ugliness, forcing us to confront the void at the heart of these characters' motivations. There’s a palpable sense of detachment, a chilling emptiness behind their extreme actions, that feels disturbingly authentic to certain facets of adolescent nihilism.

Into the Woods

Their clumsy attempt to dispose of the body leads them deep into a primal, almost mythical forest. This is where the film takes its sharpest, most polarizing turn. The gritty teen crime drama morphs into something else entirely – a grim, unsettling fairy tale. Think Hansel and Gretel, but stripped of all childlike wonder and replaced with pervasive dread. The woods themselves become a character, oppressive and labyrinthine, reflecting the characters' own lost and confused states. It’s a masterclass in atmospheric filmmaking; you can almost smell the damp earth and feel the encroaching shadows. This shift was deliberate; Ozon himself spoke about wanting to blend the realism of a crime story with the archetypal horror of classic folk tales, creating a disorienting but potent mix.

The Keeper of the Forest

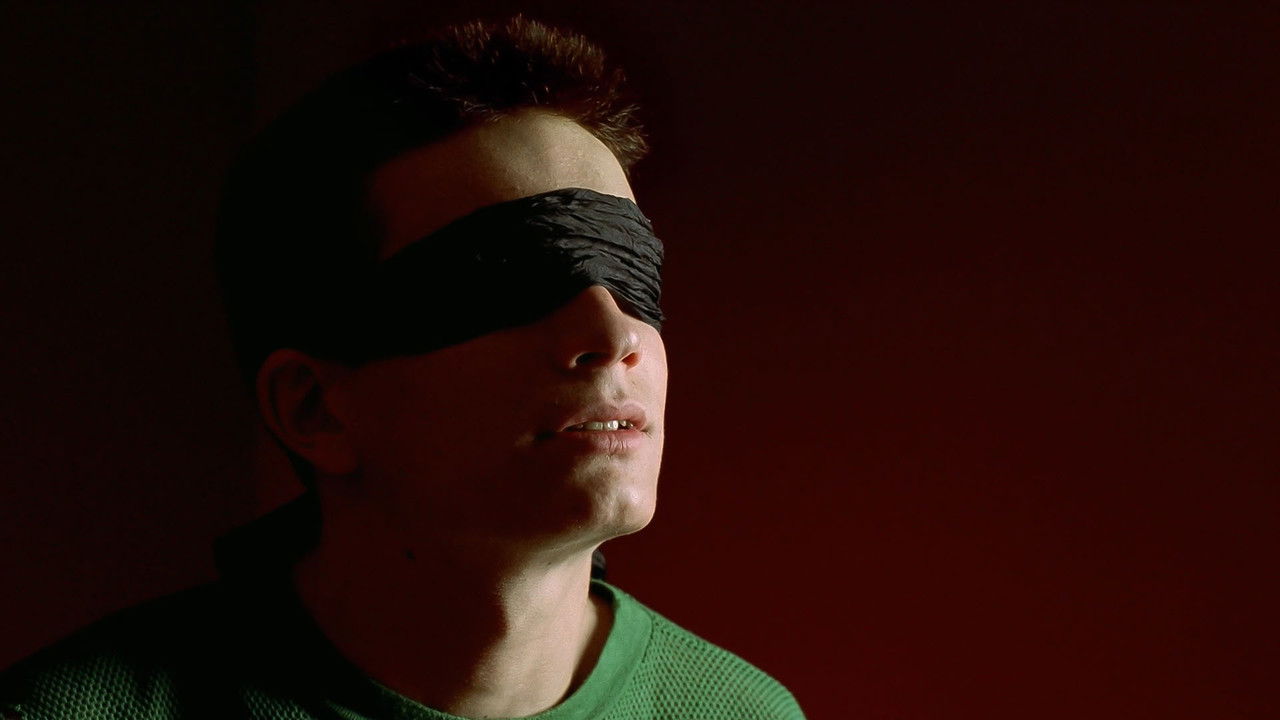

Lost and desperate, Alice and Luc stumble upon an isolated cabin inhabited by a mysterious Woodsman (Miki Manojlović). Far from a rescuer, he becomes their captor, introducing a new layer of psychological and physical horror. Manojlović's performance is magnetic – largely silent, communicating volumes through intense stares and unsettling actions. He embodies a primal force, part ogre, part strange hermit, disrupting the already fractured dynamic between the young lovers. This section is where the film truly tests its audience. The power dynamics shift dramatically, exploring themes of submission, survival, and twisted forms of intimacy that are deeply uncomfortable yet fascinating. Reportedly, the actors found the intense, isolated forest shoot challenging, contributing to the raw, frayed energy palpable on screen. Does the stark tonal shift work? For some, it’s a jarring break; for others, it's the film's most compelling stroke, elevating it beyond a simple crime story into something more allegorical and strange.

Ozon's Early Provocations

Criminal Lovers arrived relatively early in François Ozon's prolific career, following his provocative debut Sitcom (1998). It showcases his early interest in exploring taboo subjects, sexual transgression, and the darker aspects of human psychology, themes he would continue to dissect in films like Swimming Pool (2003) and In the House (2012). The film’s stark visuals, often favouring natural light and claustrophobic framing within the cabin, enhance the sense of entrapment. While lacking the budget for elaborate effects, Ozon uses suggestion and atmosphere to create a pervasive sense of unease that lingers far more effectively than any jump scare could. It feels like a film born from the darker corners of the European psyche, a stark contrast to the often more sanitized thrillers coming out of the US at the time.

A Bitter Taste That Lingers

This isn't a film designed for easy consumption. It's challenging, often unpleasant, and deliberately ambiguous. The ending offers no neat resolutions, leaving the viewer adrift with the characters' unresolved fates and the haunting imagery of the forest. Back in the day, finding a tape like Criminal Lovers felt like uncovering a secret – something raw, potentially offensive, but undeniably potent. It wasn't concerned with pleasing the audience, but with confronting them. Its blend of teen angst, brutal crime, and dark fairy tale logic makes it a unique, if divisive, entry in the late 90s cinematic landscape. It certainly wasn't a blockbuster, making perhaps only a modest return on its budget, but its impact on those who sought out Ozon's early, more confrontational work was significant.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: Criminal Lovers earns a 7 for its audacious blending of genres, its powerfully unsettling atmosphere, and its unflinching exploration of dark themes. Natacha Régnier and Jérémie Renier deliver committed, disturbing performances, and Miki Manojlović is unforgettable as the Woodsman. François Ozon's direction is confident and stylishly grim. However, the abrupt tonal shift can feel jarring, and the film's unrelenting bleakness and confrontational nature make it a difficult watch that won't resonate with everyone. It lacks the polish of Ozon's later work but possesses a raw, dangerous energy that's hard to shake.

It’s a film that burrows under your skin – a grim reminder from the VHS shelves that sometimes the most unsettling monsters aren't supernatural, but sickeningly human, lost in the woods of their own making.