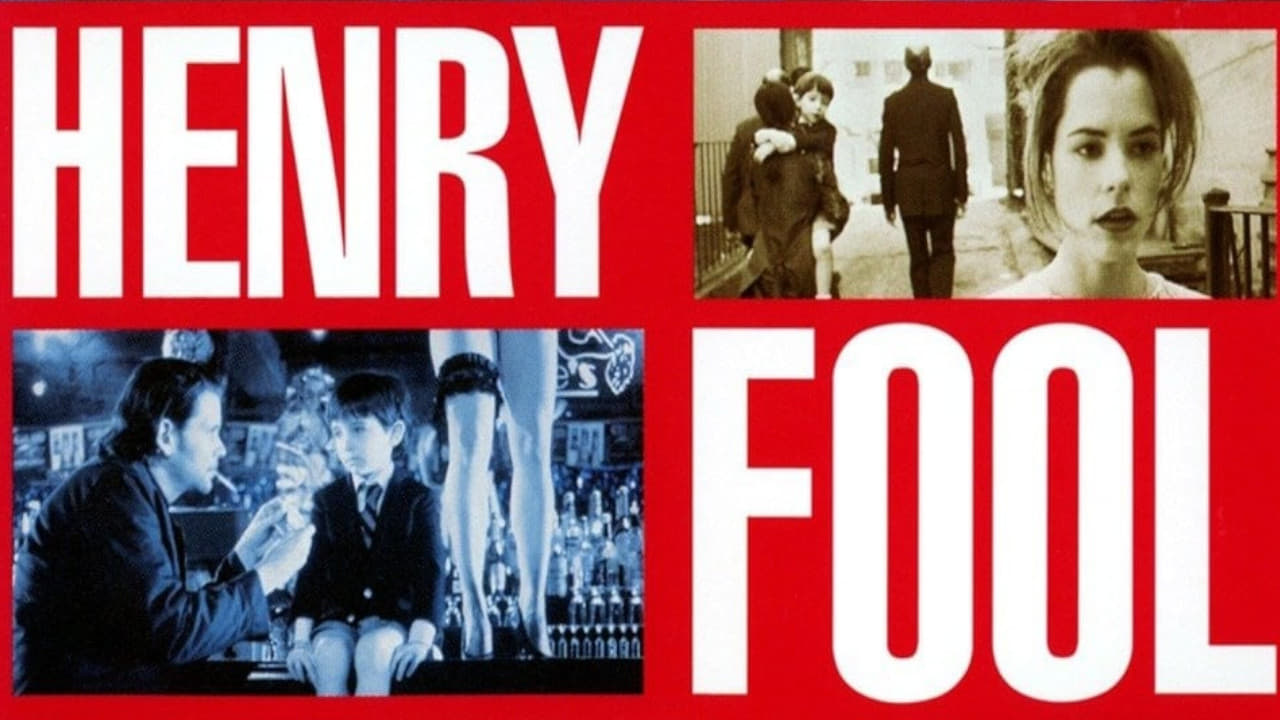

Here's a review of Henry Fool (1998) in the style of "VHS Heaven":

It starts, as these things sometimes do, with a man appearing seemingly out of nowhere. Henry Fool drifts into the basement apartment of the Grim family in Woodside, Queens, a walking paradox clad in black, trailing cigarette smoke and grandiose pronouncements about art, literature, and his own monumental (though unpublished) "Confession." He’s instantly magnetic and repellent, a low-rent Mephistopheles offering not riches, but intellectual provocation to the cripplingly shy garbage man, Simon Grim. Watching Henry Fool again, decades after its late-90s indie arrival, feels less like revisiting a film and more like unearthing a strangely potent time capsule – one filled with dial-up modems, existential dread, and the singular cinematic language of director Hal Hartley.

The Unlikely Muse of Woodside

Hartley, who already had a distinct footprint in the indie world with films like Trust (1990) and Simple Men (1992), reached a new level of ambition here. Henry Fool isn't just quirky; it digs into profound questions about the nature of creativity, the murky origins of inspiration, and the often-destructive collision between ego and artistic endeavor. Henry (Thomas Jay Ryan, in a performance that remains utterly captivating) believes himself a genius, a misunderstood titan of letters whose sprawling, chaotic manuscript holds the key to everything. Yet, his actual output seems... negligible. He talks the talk, endlessly, seducing Simon's sister Fay (Parker Posey, radiating peak 90s indie energy) and his volatile mother Mary (Maria Porter) with his pseudo-intellectual charm.

But it's Simon (James Urbaniak, delivering a masterclass in understated transformation) who becomes the unlikely vessel for genuine artistic expression. Encouraged, or perhaps simply goaded, by Henry, Simon starts writing poetry. Not flowery verse, but raw, often obscene, startlingly direct poems scratched onto notepads, capturing the grime and frustration of his life. The core irony, beautifully played, is that the supposed genius inspires true art in the man everyone dismisses. Doesn't this dynamic echo through creative history – the flamboyant talker overshadowed by the quiet doer?

Hartley's World: Deadpan, Dialogue, and Depth

If you weren't tuned into Hartley's specific frequency back in the day, his style could feel alienating. The dialogue is stylized, delivered with a rhythmic deadpan that emphasizes the words themselves, often revealing deep wells of feeling beneath the flat affect. His compositions are precise, often static, framing characters within their mundane environments in a way that feels both observational and deeply deliberate. It’s a style that demands attention, rewarding viewers who lean into its unique cadence. I recall renting this on VHS, probably from some dusty corner of the "Independent" section at Blockbuster, and being completely drawn into its strange rhythms – so different from the mainstream fare.

The film doesn't shy away from the uglier aspects of its characters. Henry is manipulative, arrogant, and possibly dangerous. Simon's newfound voice unleashes uncomfortable truths and desires. Fay, often the pragmatic center, finds herself caught between ambition and a messy, complicated love. Parker Posey, already a darling of the indie scene thanks to films like Party Girl (1995) and Dazed and Confused (1993), brings a fierce intelligence and vulnerability to Fay, making her much more than just a reactive figure.

From Humble Beginnings to Cannes Glory

For a film steeped in the grit of outer-borough New York and filled with philosophical musings, Henry Fool achieved remarkable recognition, winning the Best Screenplay award at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival. This wasn't some slick Hollywood production; it carries the hallmarks of its independent roots. Hartley often worked with a recurring troupe of actors, fostering a unique chemistry visible here between Urbaniak, Posey, and others who populated his cinematic world. You can feel the constraints of the budget sometimes, but Hartley turns it into an aesthetic – the focus remains squarely on the characters and the intricate dance of their relationships and ideas. The nearly two-and-a-half-hour runtime, unusual for Hartley, allows these complex dynamics the space they need to unfold, sometimes uncomfortably, always compellingly. Reportedly, Hartley wrote the script quickly, channeling a raw energy that translates onto the screen.

The film’s exploration of early internet culture now feels like a fascinating historical document. Simon's controversial poem achieves notoriety through nascent online forums, a pre-social media glimpse into how provocative content could suddenly find a global (or at least, national) audience, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. It felt cutting-edge then; now, it feels like a quaint prophecy of the digital deluge to come.

The Lingering Question Mark

What makes Henry Fool stick with you isn't just the sharp dialogue or the memorable performances. It’s the ambiguity. Is Henry Fool a destructive force, a parasite feeding off the Grim family? Or is he the necessary catalyst, the chaotic element required to unlock Simon's potential, however messy the process? The film refuses easy answers, leaving the viewer to ponder the symbiotic, often toxic, relationship between mentor and student, inspiration and exploitation. It forces us to ask: where does art truly come from? And what price are we willing to pay – or make others pay – for its creation? The film’s legacy continued, perhaps unexpectedly, with two sequels, Fay Grim (2006) and Ned Rifle (2014), further exploring the tangled lives of these characters, a testament to the enduring power of Hartley’s initial creation.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects Henry Fool's bold originality, its masterful performances (especially from Ryan and Urbaniak), and its intelligent, witty script that wrestles with significant themes without resorting to easy moralizing. It’s a landmark of 90s American independent cinema, showcasing Hal Hartley's unique voice at its most ambitious and rewarding. The pacing might test some, and the stylized nature is distinct, but the depth and lingering questions make it essential viewing.

Henry Fool remains a potent reminder that sometimes the most profound stories emerge not from polished surfaces, but from the messy, complicated lives unfolding just outside the frame, perhaps even scribbled down by the garbage man.