It often starts quietly, doesn't it? The seismic shift in a life. Not with dramatic thunder, but with a few mumbled words on a bustling New York City sidewalk. That’s the devastatingly mundane beginning of Erica Benton’s unwanted new chapter in Paul Mazursky’s perceptive 1978 drama, An Unmarried Woman. Watching it again, decades after first encountering it likely nestled between splashier titles on a video store shelf, its power hasn't faded. If anything, its quiet honesty feels even more resonant now.

A Portrait of Unexpected Freedom

The premise is stark: Erica (Jill Clayburgh in a career-defining performance), seemingly content in her comfortable Upper East Side life, is abruptly told by her husband Martin (Michael Murphy) that he’s leaving her for a younger woman. The rug isn't just pulled out; it's vaporized. What follows isn't a revenge plot or a frantic search for a replacement man, but a deeply felt, often messy, exploration of a woman rediscovering herself outside the defined role of "wife." Mazursky, known for character studies like Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and later Down and Out in Beverly Hills, crafts a narrative that feels less like a plotted story and more like eavesdropping on a life unfolding.

We follow Erica through the stages of grief, confusion, anger, tentative steps back into dating, reconnecting with friends, and navigating the complex terrain of single parenthood with her teenage daughter (Lisa Lucas). It's a journey marked by vulnerability but also burgeoning strength. This wasn't the typical portrayal of divorce seen in films of the era; it felt raw, authentic, and refreshingly centered on the woman's emotional and psychological experience.

The Brilliance of Clayburgh

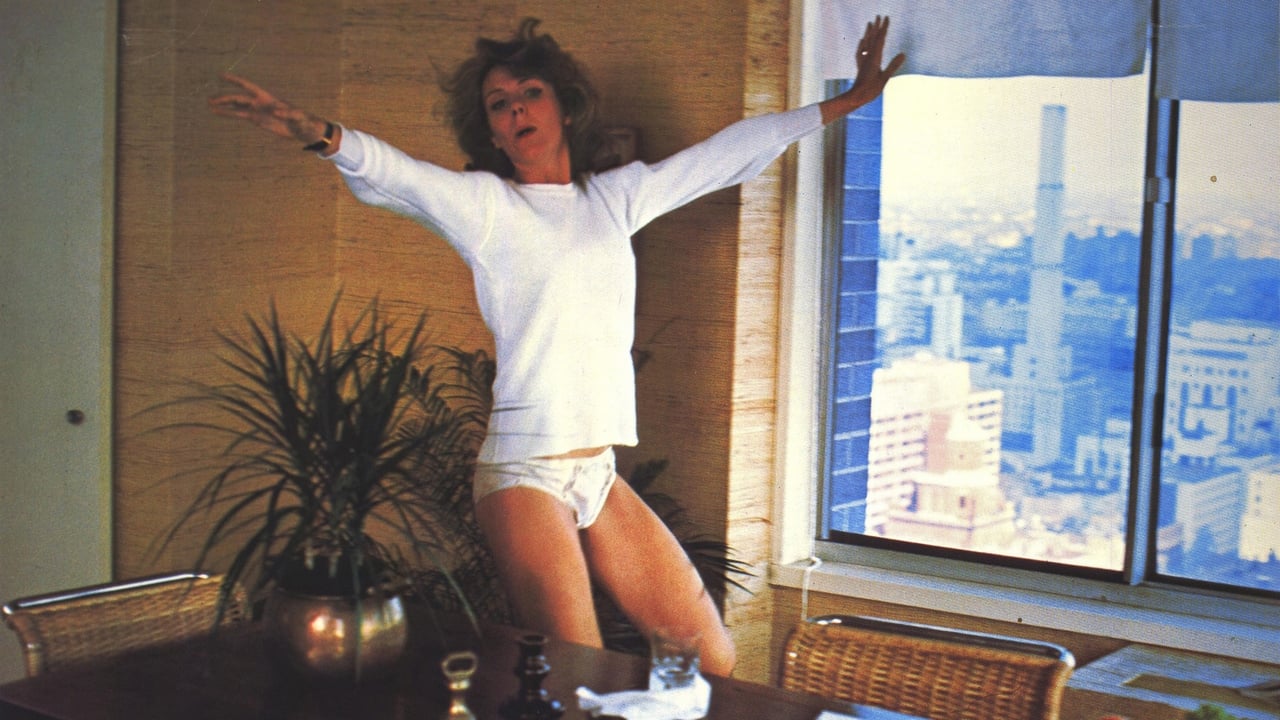

Let's be clear: this film belongs to Jill Clayburgh. Her performance is a masterclass in nuanced naturalism. She doesn’t just act the part; she embodies Erica’s turmoil and eventual resilience. Watch her face in the immediate aftermath of Martin’s confession – the shock giving way to a dawning, sickening realization. Or later, the sheer awkwardness and terror of a first date after years of marriage. Clayburgh allows Erica to be flawed, uncertain, sometimes irritatingly self-absorbed, but always profoundly human. There’s a scene where she dances alone in her apartment, a moment of pure, unadulterated release and rediscovery – it’s utterly captivating and speaks volumes without a word. It’s no surprise she earned an Oscar nomination for this role; it feels less like acting and more like witnessing.

New York as a Character

Mazursky uses late-70s New York City not just as a backdrop, but as an integral part of Erica’s journey. The art galleries of SoHo, the bustling streets, the anonymity and potential of the city itself mirror her own state of flux. It looks and feels authentic – a lived-in world that grounds the emotional drama. This wasn't a Hollywood fantasy of New York; it felt like the city many experienced, complete with its anxieties and possibilities. The film breathes the atmosphere of that specific time and place, something that adds immeasurably to its texture, especially viewed through the lens of nostalgia. Remember that specific grit and energy of late 70s NYC cinema? It's captured perfectly here.

Navigating New Relationships

The film doesn't shy away from the complexities of post-divorce romance. Erica's affair with Saul (Alan Bates), a charismatic but emotionally abstract painter, is particularly well-drawn. Bates brings his signature blend of charm and danger to the role. Their relationship feels passionate but also precarious, highlighting the difficulties of forming new connections under the shadow of past hurt. It avoids easy answers or fairytale endings, presenting the relationship, like Erica's broader journey, as a work in progress. Is finding a new man the goal, or is it part of the larger process of finding oneself? The film wisely leans towards the latter.

Lasting Impressions

An Unmarried Woman arrived at a time of significant social change, reflecting the burgeoning feminist movement and shifting perspectives on marriage and female identity. It felt important then, offering a complex, empathetic portrait that resonated deeply with audiences seeking more mature and realistic depictions of women's lives. Some aspects might feel dated now – the specific cultural references, perhaps some of the therapy-speak – but the core emotional truths remain remarkably potent. The struggle for independence, the fear of the unknown, the pain of betrayal, and the eventual, empowering realization that one can survive and even thrive after upheaval – these themes are timeless.

I recall finding this on VHS, perhaps in the slightly more "serious drama" section of the local rental place, feeling like I was watching something truly grown-up. It lacked explosions or car chases, but its emotional honesty hit just as hard. It was a film that trusted its audience to connect with subtle character work and relatable human drama.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional central performance, its sensitive and intelligent script, Paul Mazursky's nuanced direction, and its enduring relevance. Jill Clayburgh's portrayal of Erica is simply unforgettable, capturing a specific moment of female awakening with grace and power. While a product of its time, its emotional core remains incredibly strong and insightful.

What lingers most after the credits roll is the quiet triumph of Erica’s journey. It’s not about finding another man to complete her, but about finding the strength and resilience within herself. An Unmarried Woman remains a poignant, beautifully acted testament to the messy, challenging, and ultimately liberating process of starting over.