There are certain films that don’t just flicker on the screen; they sear themselves into your memory. They bypass casual viewing and demand a confrontation. Gary Oldman’s directorial debut, Nil by Mouth (1997), is emphatically one of those films. I recall picking up the VHS, perhaps drawn by Oldman’s name – an actor known for volcanic transformations – or maybe Ray Winstone’s familiar, formidable presence. What awaited wasn’t entertainment in the conventional sense, but a descent into a brutal, cyclical reality that felt disturbingly, undeniably true. It’s a film that leaves you reeling, not with plot twists, but with the sheer weight of its authenticity.

A Window Onto a Scarred Landscape

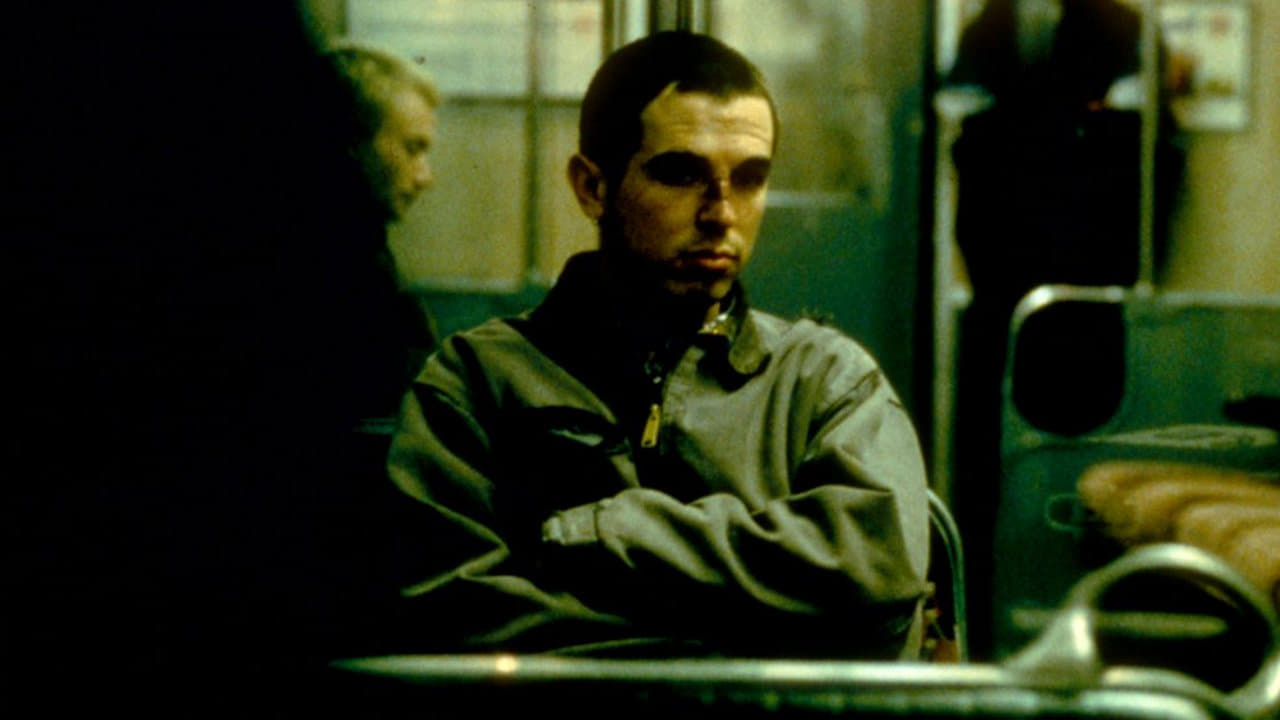

From the opening frames, Nil by Mouth plunges the viewer into the suffocating atmosphere of working-class South East London. There’s no gentle introduction, no easing into this world of nicotine-stained pubs, cramped flats, and simmering resentments. Oldman, drawing heavily from his own upbringing, doesn't romanticize or judge; he simply presents. The camera often feels intrusive yet invisible, lingering on faces etched with hardship, capturing the casual violence and desperate camaraderie that defines the lives of Raymond (Ray Winstone), his wife Valerie (Kathy Burke), her drug-addicted brother Billy (Charlie Creed-Miles), and their extended family, including matriarch Janet (Laila Morse). The dialogue, famously profane and relentlessly authentic, isn’t just for shock value; it’s the jagged poetry of lives lived on the edge, where words are often weapons or shields.

Oldman Behind the Lens: A Startling Debut

Knowing Gary Oldman primarily as the chameleon actor of films like Sid and Nancy (1986) or Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), his transition to directing with Nil by Mouth was astonishing. There’s a raw confidence here, an absolute commitment to capturing truth without flinching. He employs long, often static takes, forcing us to witness uncomfortable moments in their entirety. There's little visual flourish; the power comes from the performances he elicits and the unflinching gaze he casts upon his characters' lives. It’s fascinating to note that Oldman reportedly sunk a significant amount of his own money into the production when initial funding proved difficult – a testament to his personal investment in this story. Filmed on location in Deptford, New Cross, and Bermondsey, the very streets Oldman grew up on, the film achieves a sense of place that feels utterly lived-in and inescapable.

Performances Forged in Fire

The acting in Nil by Mouth isn't just good; it's monumental. Ray Winstone, already a respected figure from films like Scum (1979), delivers a career-defining performance as Ray. He embodies toxic masculinity fueled by insecurity, alcohol, and a terrifying capacity for sudden violence. Yet, crucially, Winstone never allows Ray to become a mere monster; glimpses of vulnerability, however warped, make him terrifyingly human. His explosive rage feels chillingly real, a force of nature tearing through his own family.

Opposite him, Kathy Burke is simply extraordinary as Valerie. Her portrayal of a woman trapped in a cycle of abuse, desperately clinging to shreds of hope and love amidst the wreckage, is devastatingly nuanced. She conveys oceans of pain, resilience, and weary endurance, often with just a look or a tremor in her voice. Her performance rightly earned her the Best Actress award at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival, a major recognition that shone a spotlight on the film's raw power. It’s also worth noting that Laila Morse, who plays Val’s stoic mother Janet, is actually Gary Oldman's older sister, Maureen Oldman, making her screen debut here under a stage name that's an anagram of "mia sorella" (Italian for "my sister"). Her grounded presence adds another layer of authenticity.

Retro Fun Facts: Grit Behind the Scenes

The film’s unflinching nature caused ripples. Its extreme language and depictions of violence led to intense discussions with ratings boards; it flirted with an NC-17 rating in the US before securing an R, and received an 18 certificate in the UK, effectively limiting its audience but preserving Oldman's vision. The original cut was reportedly closer to three hours, hinting at even more immersive, perhaps harrowing, material. Oldman's insistence on realism extended to the casting of his own sister and shooting in his old neighbourhoods, blurring the line between fiction and autobiography. The film wasn't a box office smash, but its critical reception, particularly Burke's Cannes win and Oldman's Palme d'Or nomination, cemented its status as a significant, albeit challenging, piece of British cinema.

An Uncomfortable, Necessary Truth

Nil by Mouth is not an easy watch. It offers no easy answers, no triumphant narrative arcs. It portrays the corrosive effects of poverty, addiction, domestic violence, and the crushing weight of generational trauma with an honesty that can feel overwhelming. Does it offer hope? Perhaps only in the resilience flickering in Valerie's eyes, or the moments of flawed connection amidst the chaos. What lingers most after the credits roll is the film's refusal to look away, its insistence on showing lives often hidden or ignored. It forces a reckoning with uncomfortable realities, questioning the cycles we inherit and perpetuate.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's artistic achievement, its powerhouse performances, and its brutal, undeniable honesty. It's a near-masterpiece of social realism, masterfully directed and acted. The deduction of a point acknowledges its extreme nature, which makes it a film respected and admired more than perhaps 'enjoyed' in the traditional sense. It's a harrowing experience, but an essential one for anyone interested in powerful, uncompromising cinema from the 90s.

Nil by Mouth remains a landmark – a raw nerve exposed, a film that uses the specificity of its South London setting to speak universal truths about pain, survival, and the desperate human need for connection, even in the darkest corners. It doesn't just show; it makes you feel.