There are films that explode onto the screen, demanding attention with noise and spectacle, the kind that dominated the New Releases wall at Blockbuster. And then there are films like Somersault in a Coffin (Turkish: Tabutta Rövaşata), whispers found perhaps deeper in the aisles, maybe in that slightly intimidating 'World Cinema' section on a worn VHS tape. Released in 1996, this debut feature from writer-director Derviş Zaim doesn't shout. Instead, it settles under your skin with a quiet, melancholic chill, leaving an impression far heavier than its humble origins might suggest. It’s the kind of discovery that reminds you why seeking out those less-heralded tapes was often so rewarding.

A Chill Wind Through Rumelihisarı

The film introduces us to Mahsun, a man existing on the absolute fringes of Istanbul society. He’s homeless, jobless, friendless, save for the stray dogs he shares scraps with. His crime? He steals cars. Not for joyrides, not to sell parts, but simply to sleep in them, to find a fleeting moment of warmth and shelter from the cold Bosphorus nights. It’s a premise so stark, so fundamentally rooted in desperation, that it immediately forces a confrontation with uncomfortable truths about poverty and survival. Zaim crafts an atmosphere thick with the damp cold of the Rumelihisarı neighborhood, the ancient fortress walls overlooking the strait serving as a constant, silent witness to Mahsun's struggles. This isn't the vibrant, bustling Istanbul often seen on screen; it's a place of shadows, quiet despair, and the gnawing reality of being utterly alone.

The Unforgettable Mahsun

At the heart of Somersault in a Coffin is the astonishing performance by Ahmet Uğurlu as Mahsun. It's a portrayal devoid of vanity or melodrama, built instead on subtle physicality and expressive silence. Uğurlu embodies Mahsun's weariness, his perpetual hunger (often stealing bread with the same necessity as he steals cars), and his moments of almost childlike vulnerability. Watch the way he curls up in the backseat of a stolen vehicle, the brief flicker of contentment before sleep, or his awkward attempts at connection – it feels painfully, undeniably real. There’s a profound sadness in his eyes, but also a stubborn spark of life, a refusal to completely disappear. What does his nightly ritual reveal? Is it merely survival, or is there a deeper yearning for normalcy, for the simple dignity of having a place, even a borrowed one, to rest his head? Uğurlu makes Mahsun unforgettable, a character etched not through dialogue, but through quiet desperation and resilience. It's reported that Zaim based Mahsun on a real homeless man he knew from the area, someone who indeed stole cars simply for shelter, lending the portrayal an unnerving layer of authenticity.

More Than Just Stealing Cars

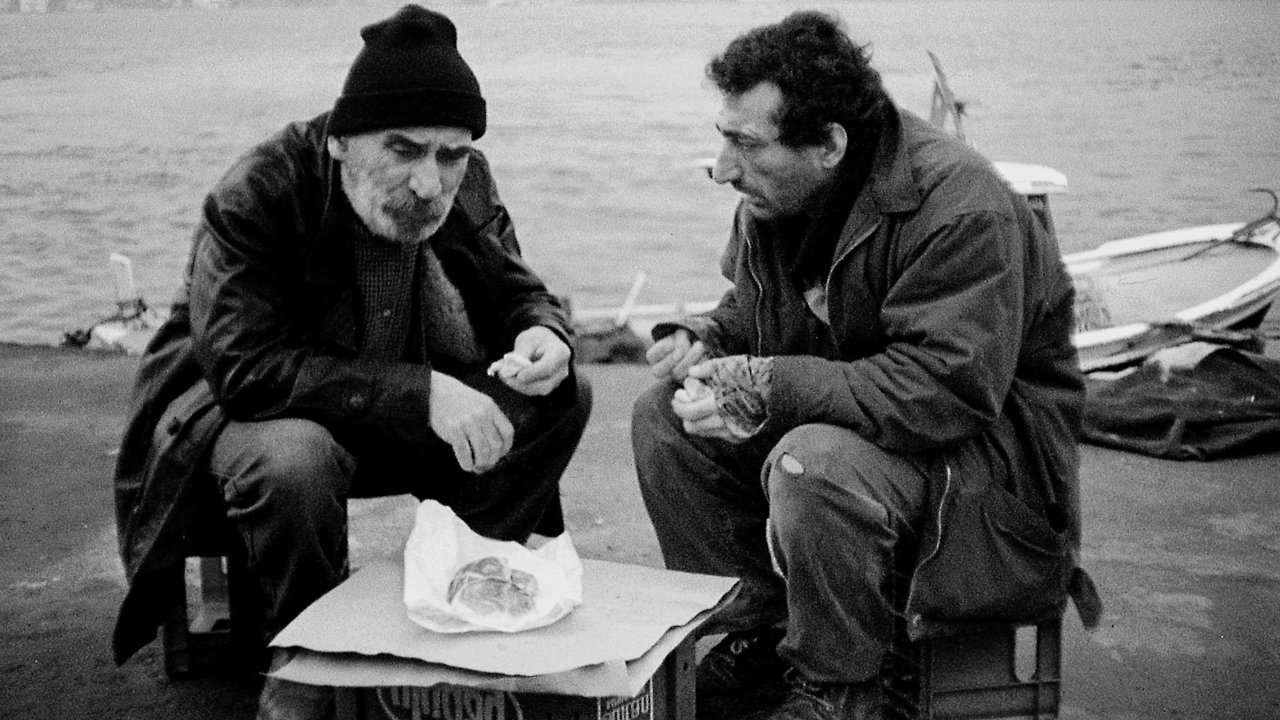

While Mahsun’s car-stealing provides the narrative spine, the film reaches deeper. It’s a meditation on alienation in the modern city, the invisibility of the poor, and the fundamental human need for connection and purpose. Mahsun occasionally interacts with others – the fishermen, the tea house owner Reis (played with weary authority by the legendary Tuncel Kurtiz, a towering figure in Turkish cinema known for decades of powerful roles), and a heroin-addicted woman (Ayşen Aydemir) whose own struggles mirror Mahsun's in different ways. These encounters are brief, often fraught with misunderstanding or transactional necessity, highlighting the chasm between Mahsun and the world around him. He cares for a peacock, a symbol of beauty tragically out of place in his grim reality, suggesting a capacity for tenderness buried beneath the hardship. Zaim avoids easy sentimentality; there are no miraculous rescues or sudden turns of fortune. Instead, the film maintains its melancholic tone, forcing us to consider the systemic issues and human cost of extreme poverty.

A Director's Confident Debut

For a debut feature reportedly made on a shoestring budget (figures around $100,000 are often cited), Somersault in a Coffin demonstrates remarkable control and vision. Derviş Zaim employs a minimalist aesthetic, letting the locations and Uğurlu's performance carry the weight. The pacing is deliberate, mirroring the slow, repetitive rhythm of Mahsun's existence. There are no flashy camera tricks, just observant framing that emphasizes Mahsun’s isolation against the backdrop of the city and the imposing Rumeli Fortress. The film swept awards ceremonies in Turkey upon its release (including multiple Golden Oranges at Antalya Film Festival), instantly establishing Zaim as a significant voice in contemporary Turkish cinema. The title itself, Tabutta Rövaşata, translates literally to "Somersault in a Coffin." It's a visceral, enigmatic phrase – perhaps suggesting a final, desperate act of defiance or trapped energy within an inescapable fate. It perfectly encapsulates the film’s blend of bleakness and flickering humanity.

Finding Gold in the Foreign Aisle

Discovering Somersault in a Coffin on VHS back in the day wouldn't have been like grabbing the latest Schwarzenegger flick. It required a bit more digging, a willingness to step outside the mainstream. But finding it felt like unearthing something special, something raw and truthful. It lacked the polish of Hollywood, but it possessed an emotional honesty that resonated deeply. It didn't offer easy answers or catharsis, but it lingered, prompting reflection long after the tape clicked off and the static filled the CRT screen. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most powerful stories are found in the quietest corners.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score is earned through its profound humanity, the unforgettable central performance by Ahmet Uğurlu, and Derviş Zaim's assured, minimalist direction. Its stark portrayal of poverty and alienation is unflinching yet deeply empathetic, avoiding sentimentality while capturing a universal ache for dignity and connection. The low budget becomes irrelevant in the face of such powerful, authentic storytelling. Minor pacing dips in the middle barely detract from its overall impact.

Somersault in a Coffin remains a haunting and vital piece of cinema. It doesn't just show us a life on the margins; it invites us to feel the cold, the loneliness, and the stubborn flicker of hope that persists even in the most desolate circumstances. What does it truly mean to be seen, even for a moment, in a world determined to look away?