There's a quiet weight that settles over you after watching Akira Kurosawa's Rhapsody in August (1991). It’s not the thunderous clash of samurai swords or the epic sweep of feudal battles that many associate with the master director, especially after the staggering achievement of Ran (1985) just a few years prior. Instead, this film, arriving on video store shelves in the early 90s, offered something far more intimate, yet no less profound: a gentle, sometimes uneasy, meditation on memory, trauma, and the lingering shadows of war across generations. Finding this tape felt different; it wasn't an action blockbuster, but a hushed invitation into something deeply personal.

Whispers from the Past Near Nagasaki

The premise is deceptively simple. Four young grandchildren spend a summer holiday with their aging grandmother, Kane (Sachiko Murase), in the countryside near Nagasaki. Decades have passed since the atomic bombing claimed her husband, yet the event remains an unspoken, defining presence in her life. The children, products of a modern, prosperous Japan, initially struggle to grasp the enormity of what their grandmother endured. Their summer becomes an unexpected history lesson, not through textbooks, but through Kane's fragmented recollections, her quiet rituals, and the very landscape scarred by memory. Kurosawa, working from the novel Nabe no naka by Kiyoko Murata, crafts an atmosphere thick with the unspoken, where the beauty of the rural setting contrasts sharply with the invisible wounds of the past.

A Towering Performance of Quiet Dignity

At the heart of Rhapsody in August is the unforgettable performance by Sachiko Murase as Kane. In her late 70s at the time of filming (remarkably, it was one of her final major roles after a long career primarily in theatre and supporting film parts), Murase embodies the grandmother with a profound sense of lived history. There’s no overt melodrama; her grief and resilience are conveyed through subtle gestures, faraway looks, and a voice that carries the weight of decades. Watch the scene where she recounts the day of the bombing – it’s delivered with a stoicism that makes the underlying pain almost unbearable. It's a performance built on authenticity, making Kane feel less like a character and more like a cherished elder sharing fragments of a painful truth. Her interactions with the children, played with natural curiosity and eventual understanding by the young cast, form the film's emotional core. You see the generational gap, not as a source of conflict, but as a space Kurosawa gently explores, questioning how collective memory is passed down, or sometimes, tragically, fades.

Kurosawa's Gentle, Searching Lens

While lacking the visual dynamism of his earlier epics, Kurosawa's directorial hand is unmistakable. His framing is precise, often lingering on faces or elements of nature – the vibrant roses that become a recurring motif, the symbolic storm that mirrors Kane's turbulent memories. Working again with composer Shinichiro Ikebe, whose score subtly underscores the film's emotional currents, Kurosawa opts for a patient, observational style. He allows moments of silence to speak volumes, trusting the audience to connect with the characters' inner worlds. This wasn't the Kurosawa of sweeping action, but the elder statesman, aged 81 during production, using his craft to grapple with one of his nation's most profound traumas. It's worth noting that Kurosawa himself wasn't directly affected by the bombing in the way Kane's character was, making his approach one of empathetic exploration rather than personal testimony.

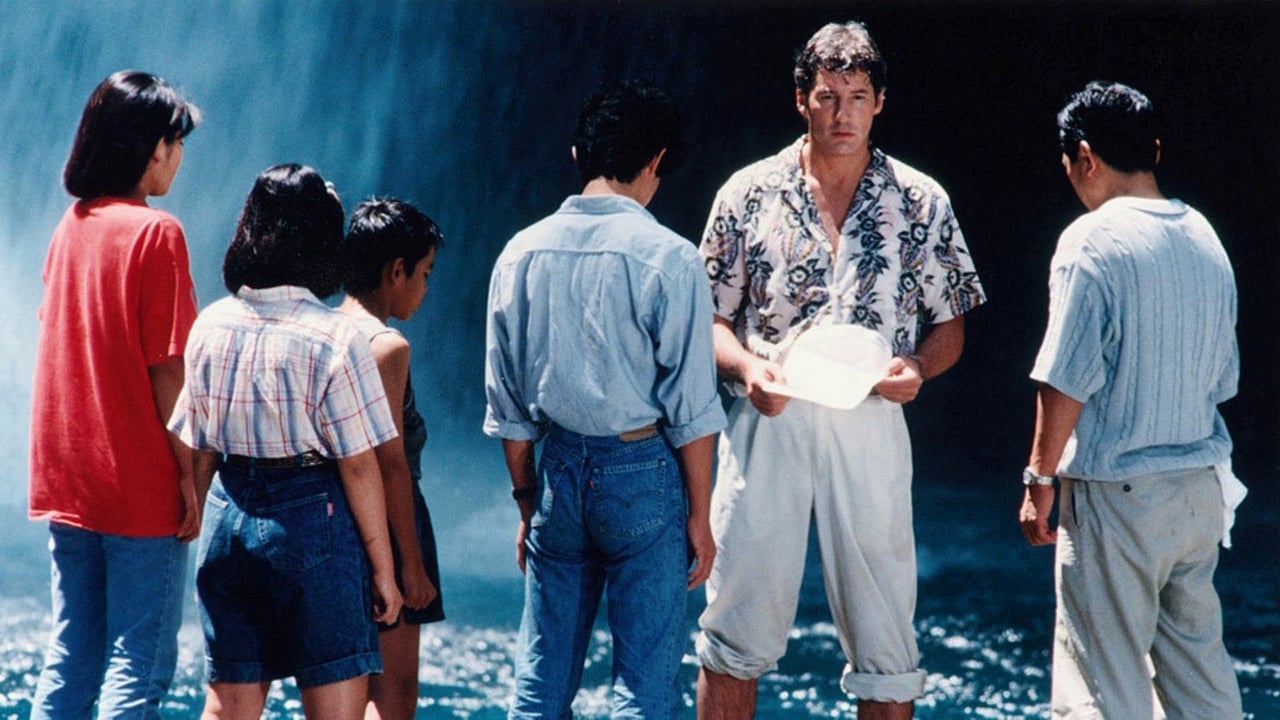

An American Cousin and Lingering Questions

The film generated some controversy, particularly in the West, partly due to the introduction of Kane's Japanese-American relative, Clark, played by Richard Gere. Gere, then a major Hollywood star known for films like Pretty Woman (1990), took the role reportedly out of deep respect for Kurosawa and an interest in Japanese culture, even accepting a significantly lower salary. His character arrives intending to apologize on behalf of America, a gesture Kane gently deflects. Some critics felt the film focused too heavily on Japanese victimhood without adequately acknowledging Japan's own wartime aggression. Clark’s character arc, representing an outsider grappling with this complex legacy, adds another dimension, but also highlights the difficulties in reconciling vastly different historical perspectives. Does his presence offer a path to healing, or does it inadvertently simplify the narrative? It remains a point of discussion, a question the film perhaps intentionally leaves open. Kurosawa stated he wanted to depict the bomb's effects on ordinary people, a universal tragedy, but the specific historical context inevitably invited debate.

The Weight of Memory on VHS

Watching Rhapsody in August today, perhaps retrieving that well-worn VHS from a dusty shelf, feels like uncovering a quiet treasure. It lacks the immediate adrenaline rush of many 80s/90s staples, but its power lingers. It’s a film that asks us to sit with discomfort, to consider how history shapes families and individuals long after the headlines fade. It’s a testament to Kurosawa's enduring humanism, his ability to find profound stories in the intimate spaces of human experience. The film wasn't a massive box office success compared to Kurosawa's biggest hits, perhaps reflecting its challenging theme and meditative pace, but its value lies not in spectacle, but in its quiet insistence on remembrance.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable artistic merit, particularly Sachiko Murase's towering performance and Kurosawa's masterful, sensitive direction. The deliberate pacing and nuanced exploration of memory and trauma are deeply affecting. While the handling of the American perspective via Richard Gere's character sparked valid debate and might feel slightly simplistic to some viewers, the film's core emotional honesty and its power as a poignant, late-career statement from a cinematic giant are undeniable. It earns its place as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, piece of 90s world cinema readily available in the aisles of our beloved video stores.

Rhapsody in August doesn't offer easy answers, but it leaves you contemplating the echoes of the past in the present. What lingers most isn't just the sadness, but the quiet strength found in remembering, even when it hurts. A truly thoughtful piece from one of cinema's greats.