Okay, pull up a comfortable chair, maybe pour yourself something smooth. Let's talk about a film that doesn't shout, but rather invites you in for a slow burn conversation, the kind that lingers long after the screen fades to black. I'm thinking about Wayne Wang's 1995 film, Smoke. Finding this on the shelf back in the day, nestled perhaps between louder, more insistent neighbours in the 'Drama' section of the video store, felt like unearthing a quiet gem. It promised something different, something more akin to sinking into a well-loved novel than bracing for a cinematic rollercoaster. And didn't it just deliver on that promise?

### The Corner Store Crucible

At the heart of Smoke lies the Brooklyn Cigar Company, presided over by Auggie Wren, played with lived-in perfection by Harvey Keitel. This isn't just a shop; it's a neighbourhood confessional, a crossroads, a fixed point in a turning world. Wang, working from a beautifully structured screenplay by novelist Paul Auster (itself born from Auster's poignant "Auggie Wren's Christmas Story"), captures the specific rhythm of this place. It feels authentic, a snapshot of a certain kind of pre-gentrified, pre-internet Brooklyn where characters drift in and out, their lives subtly intersecting over the counter. The atmosphere is thick with the scent of tobacco, yes, but also with unspoken histories and the quiet hum of daily existence.

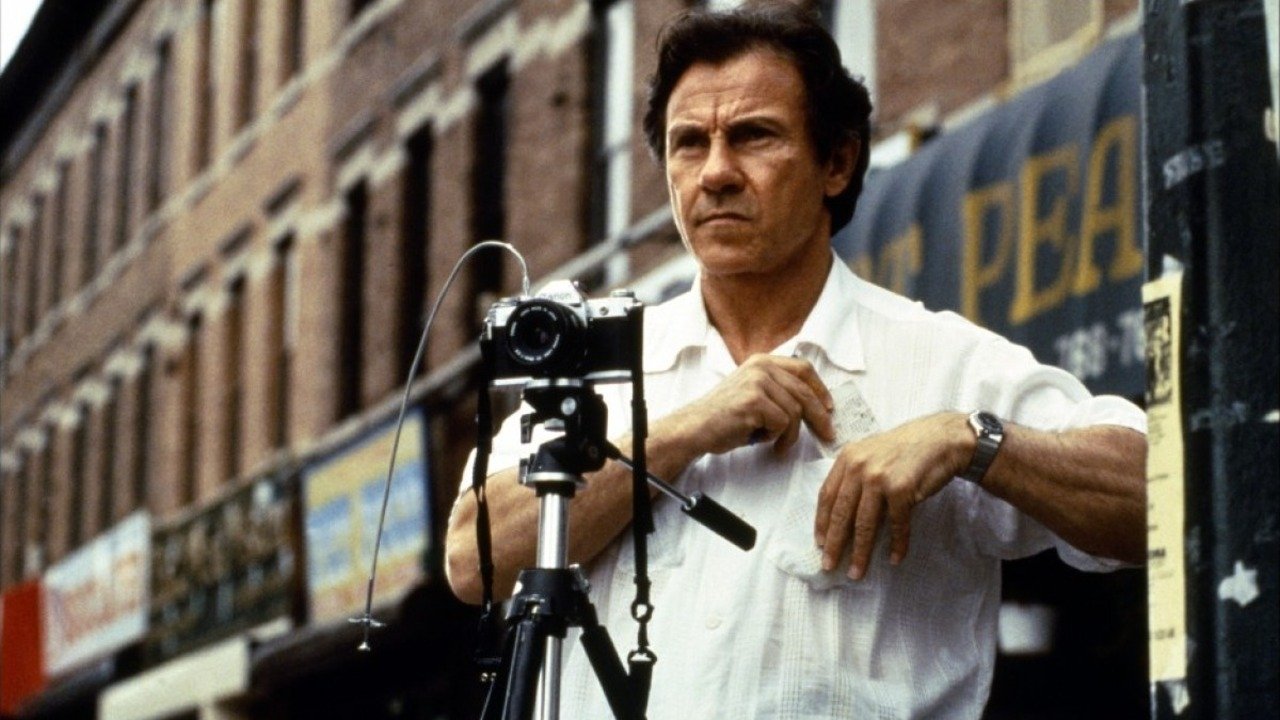

One of the film's most resonant elements is Auggie's peculiar project: photographing the exact same street corner outside his shop, every single morning at 8:00 AM, for years. Thousands of photos, seemingly identical, yet holding minute variations – the changing light, the passing faces, the subtle shifts in the urban landscape. It’s a stunning metaphor for the film itself, which asks us to look closely at the apparently mundane to find the extraordinary. Here’s a fascinating piece of trivia that deepens this aspect: those photos weren't just props. Director Wayne Wang actually took them himself over several years, capturing that specific corner (3rd Street and Seventh Avenue in Park Slope) long before filming began. Knowing this adds another layer of deliberate artistry and patience to the film's core image.

### Interwoven Threads, Quiet Truths

Smoke isn't driven by a single, propulsive plot, but rather by the gentle collision of several lives. There's Paul Benjamin (William Hurt, embodying intellectual grief with a quiet intensity), a novelist numbed by the sudden death of his wife. His path crosses with Rashid Cole (played with compelling youthful energy by Harold Perrineau Jr., years before Lost), a young man running from a troubled past and spinning elaborate tales about his identity. Then there's Ruby McNutt (Stockard Channing, fiery and vulnerable in a relatively brief but crucial appearance), an old flame of Auggie's who arrives with a desperate plea tied to their shared past. And circling these are other figures, like Cyrus Cole (Forest Whitaker), whose presence forces confrontations with uncomfortable truths.

What Paul Auster's script does so masterfully is weave these stories together not through contrived coincidences, but through the organic ebb and flow of life centered around Auggie’s shop. It explores themes of identity, loss, fatherhood (both literal and figurative), and the complex relationship between truth and fiction. How much are we defined by the stories we tell ourselves and others? When does a lie become a kind of truth, a necessary fiction to navigate the world? These aren't questions the film answers definitively, but rather ones it invites us to ponder alongside the characters.

### Performances That Breathe

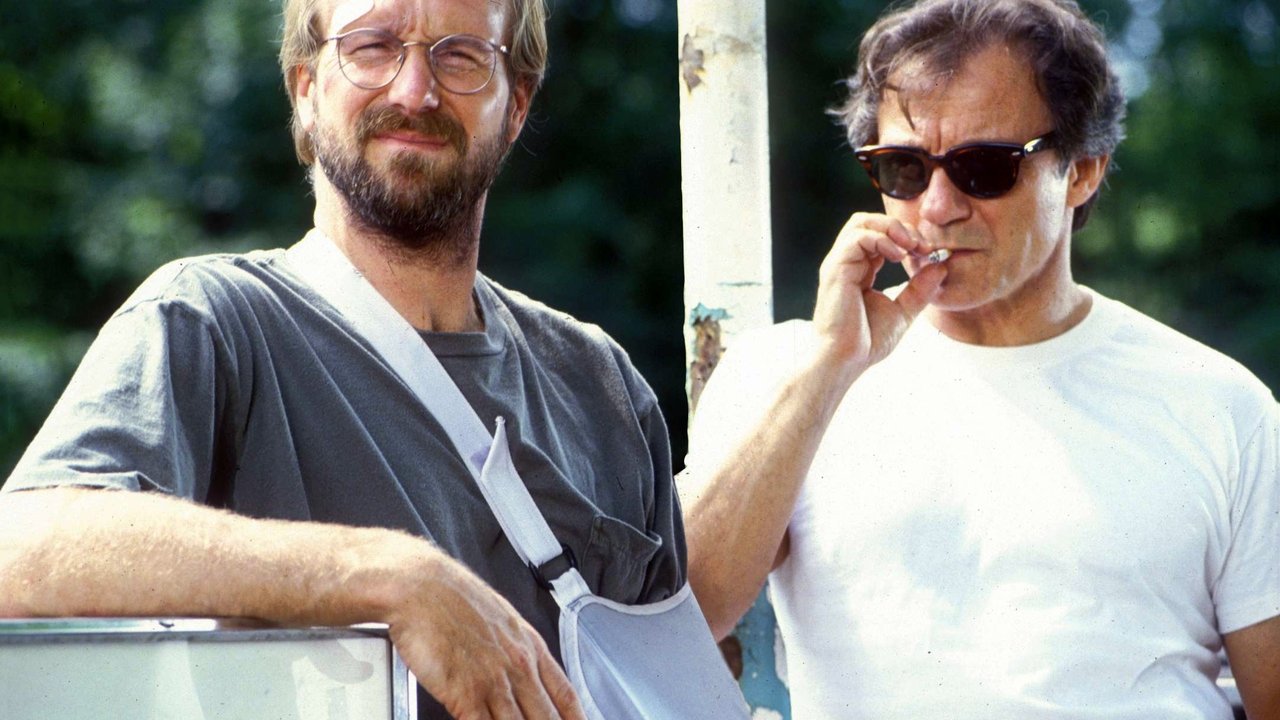

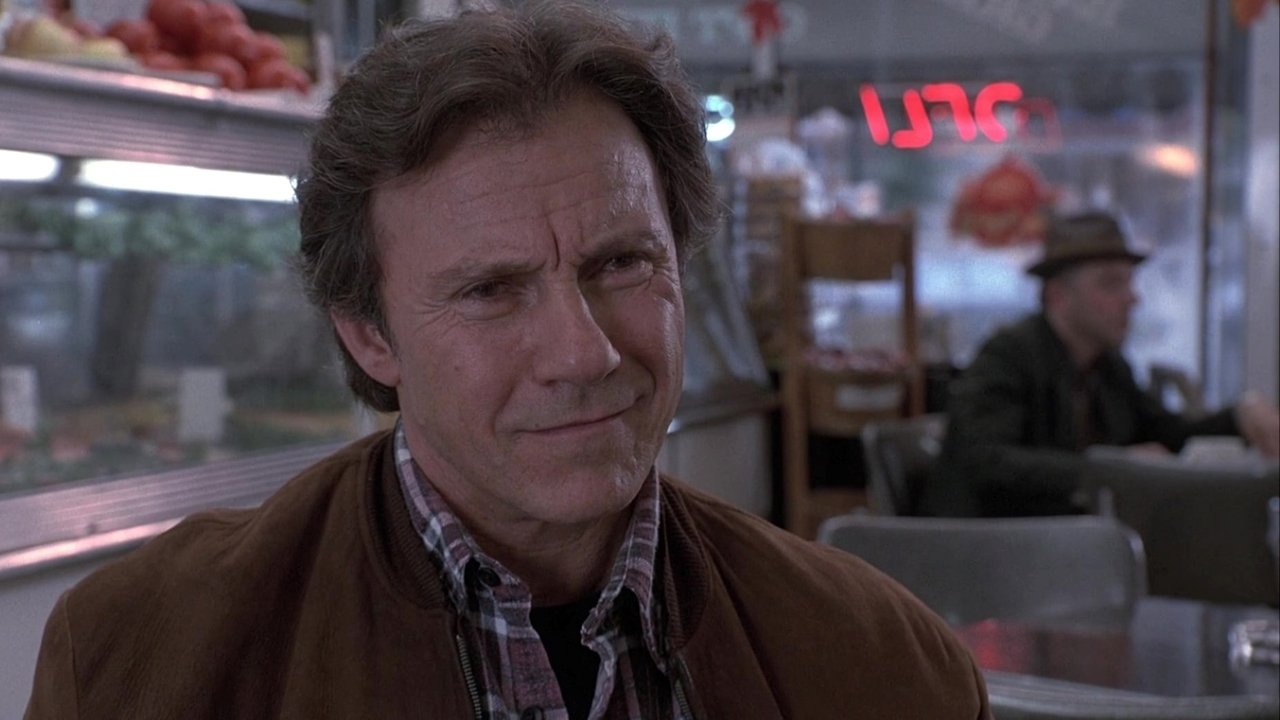

The acting in Smoke is uniformly excellent, characterized by its naturalism and restraint. Harvey Keitel, often known for more explosive roles (think Reservoir Dogs (1992) or Bad Lieutenant (1992)), grounds the entire film. His Auggie is watchful, philosophical, occasionally gruff, but deeply empathetic. He listens more than he speaks, embodying the film's observational quality. You believe he’s run this shop for decades. William Hurt, fresh off critically noted roles in films like The Accidental Tourist (1988), perfectly captures the intellectual paralysis of grief, his interactions often tentative, searching. The scenes between Keitel and Hurt, exploring friendship and the slow process of healing, feel remarkably genuine, apparently benefiting from Wang’s encouragement of subtle improvisation. Even smaller roles resonate, contributing to the film’s rich tapestry of humanity.

### A Different Kind of 90s Film

In an era often remembered for grunge, burgeoning CGI, and high-concept blockbusters, Smoke stood out. It represented a certain kind of thoughtful, character-driven American independent cinema that felt both sophisticated and accessible. Watching it on VHS offered a different kind of satisfaction – the quiet click of the tape engaging, the slightly fuzzy warmth of the CRT screen somehow complementing the film's intimate, analogue feel. It wasn't aiming for spectacle, but for connection.

Interestingly, the creative energy on set was so potent that Wang and Auster, along with many of the cast members, immediately shot a companion piece, Blue in the Face (1995). Using leftover film stock from Smoke and largely improvised, it’s a looser, funkier, more chaotic celebration of Brooklyn life, featuring cameos from Lou Reed, Michael J. Fox, Madonna, and Jim Jarmusch. While Smoke is the carefully composed photograph, Blue in the Face is the vibrant, messy street party happening just outside the frame – knowing about it adds a fun layer to the Smoke experience. Made for around $7 million, Smoke found modest success (grossing over $8 million domestically, considerably more worldwide), proving there was an audience hungry for these kinds of nuanced stories, even if they wouldn't break box office records. It also garnered critical acclaim, notably winning the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

### Lasting Impression

Smoke is a film that rewards patience. It doesn't grab you by the collar; it gently takes your arm and asks you to slow down, to observe, to listen. It suggests that extraordinary stories are hidden within ordinary lives, waiting to be noticed, like the subtle differences in Auggie's daily photographs. It’s a film about the weight of time, the power of connection, and the stories we construct to make sense of it all.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's masterful blend of Paul Auster's literate script, Wayne Wang's sensitive direction, and the superb, understated performances, particularly from Harvey Keitel and William Hurt. The film achieves precisely what it sets out to do: create a deeply human, atmospheric, and thought-provoking portrait of intersecting lives. Its quiet power and thematic richness feel earned, resonating long after the credits roll. It loses a single point perhaps only because its deliberately measured pace might test the patience of some viewers, but for those willing to settle into its rhythm, it's a profound experience.

What Smoke leaves you with isn't a neat resolution, but a feeling – a sense of shared humanity, the quiet beauty of the everyday, and the enduring truth that everyone, truly, has a story worth telling. Doesn't that feel like something worth remembering, especially now?