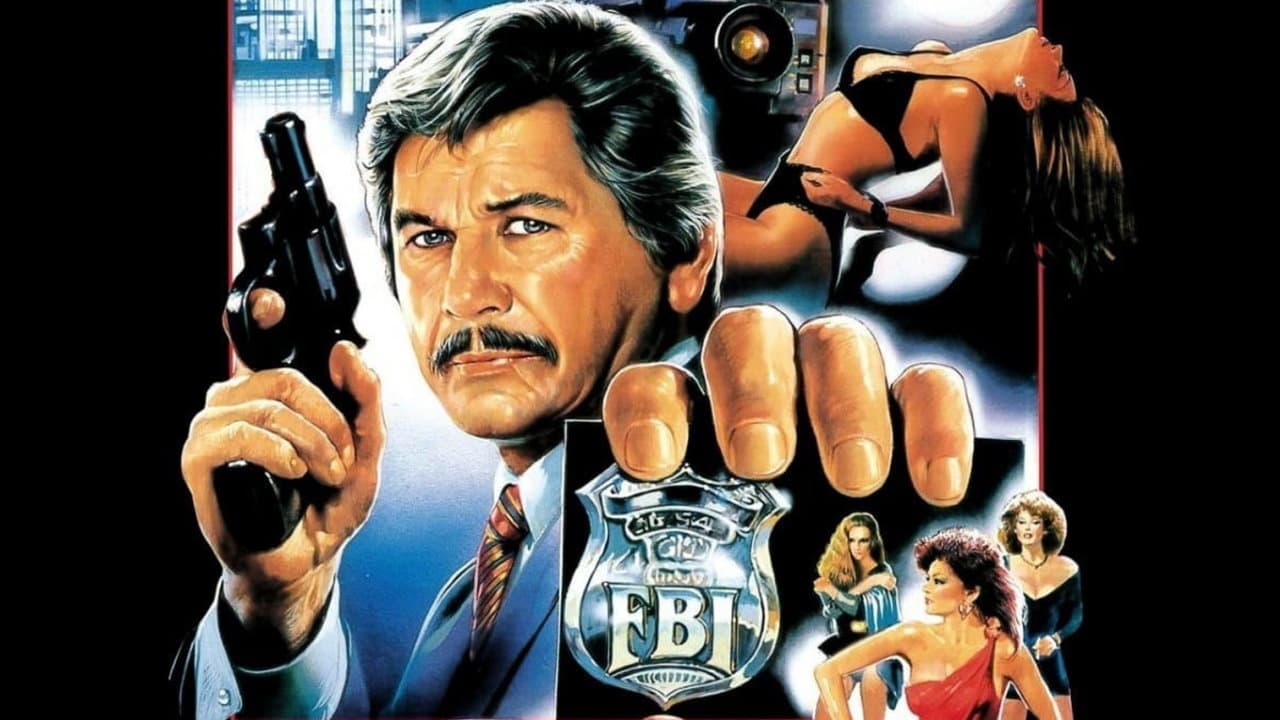

The final pairing of director J. Lee Thompson and star Charles Bronson wasn't a victory lap; it was a descent into the kind of urban decay and moral squalor that leaves a residue. Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects (1989) arrived near the tail end of the VHS boom, a tape whose stark cover art often promised straightforward Bronson vigilantism but delivered something far more unsettling. This wasn't just another Death Wish sequel; it felt different, uglier, hitting nerves that other action thrillers of the era wouldn't dare touch. Watching it felt like handling something illicit, a transmission from the grimiest corners of late-80s Los Angeles.

A City's Dark Underbelly

From the opening moments, Thompson, a veteran craftsman who gave us classics like The Guns of Navarone (1961) and the original Cape Fear (1962), plunges us into a world steeped in neon-lit sleaze and palpable danger. The film follows LAPD Vice Detective Hiroshi Hada (Charles Bronson), a man simmering with barely contained rage, not just at the criminals he pursues, but seemingly at the world itself. His path collides brutally with that of a seemingly respectable Japanese businessman (James Pax) harboring monstrous secrets, all while Hada investigates a child exploitation ring that forces him – and the audience – to confront deeply uncomfortable realities. The film's title, Kinjite, translates from Japanese as "forbidden hand" or "forbidden move," but here it clearly signifies the taboo nature of its central themes.

Bronson Unfiltered

Bronson, by this point in his career, was practically Mount Rushmore carved from granite and resentment. In Kinjite, however, the usual stoic vigilantism curdles into something darker, more overtly prejudiced and volatile. Hada isn't just tough; he's deeply flawed, embodying racial biases and a simmering fury that often feels just as dangerous as the criminals he hunts. It’s a challenging performance, stripped of the wry charm sometimes found in his earlier roles. There's a scene involving Hada forcing the predatory businessman to witness the degradation he inflicts – it’s pure, unadulterated Bronson rage, almost terrifying in its intensity. This marked the ninth and final collaboration between Bronson and J. Lee Thompson, a partnership that defined a certain brand of gritty action cinema for nearly two decades, ending not with a bang, but with a grimace.

Navigating the Forbidden

Let's be clear: Kinjite is exploitation cinema. It tackles the horrific subject of child sexual abuse with the subtlety of a sledgehammer. The film walks a precarious line, often stumbling into uncomfortable territory. The portrayal of the Japanese businessman leans heavily on stereotypes prevalent at the time, reflecting anxieties about foreign economic influence mixed with xenophobia. It's undeniably problematic through a modern lens. Yet, there's a raw, confrontational energy to it. Thompson doesn't flinch, presenting the subject matter with a starkness that, while potentially exploitative, also generates genuine unease. It's a far cry from the often sanitized action fare of the era. Did the film genuinely need to be this explicit? Probably not, but it certainly ensured Kinjite wasn't easily forgotten. It felt like a film Golan-Globus (post-Cannon split, but still carrying that DNA) had to make – provocative, boundary-pushing, and guaranteed to cause a stir.

Grime as Aesthetic

The film looks and feels like late-night LA grit. Thompson and his cinematographer capture the city not as a glamorous backdrop, but as a sprawling network of dark alleys, cheap motels, and anonymous office buildings where predators lurk. The score is appropriately menacing, all synthesized dread and pulsing rhythms that underscore the tension. The practical effects, while sparse, focus on the visceral impact of violence rather than flashy spectacle. You remember the look on Bronson’s face, the desperation in a victim’s eyes, the oppressive atmosphere of a city holding its breath. The production likely operated on a modest budget, a hallmark of many Golan-Globus financed pictures, forcing a focus on street-level realism over expensive set pieces, which arguably enhances the film's dirty, grounded feel.

Legacy of Unease

Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects wasn't a massive box office hit, pulling in around $3.5 million domestically against its budget (precise figures are murky, typical of the producers), but it certainly lingered in the minds of those who rented it. It remains one of Bronson's most controversial films, often cited as either a daringly grim thriller or an irredeemably sleazy piece of exploitation, sometimes both in the same breath. It lacks the iconic status of Death Wish (1974) but possesses a unique, disturbing power. It features Juan Fernández as a particularly memorable, reptilian pimp named "Duke," a role that cemented his typecasting as a go-to slimeball antagonist in many 80s and 90s actioners. Doesn't his unnerving presence still send a chill down your spine?

For fans of Bronson's later, rougher work, or those fascinated by the darker, less polished corners of 80s crime cinema, Kinjite offers a potent, if often unpleasant, viewing experience. It’s a film that feels dangerous, not just in its subject matter, but in its raw, unfiltered portrayal of anger and societal decay.

VHS Heaven Rating: 5/10

Justification: Kinjite earns points for its unflinching tone, Bronson's intense (if problematic) performance, and its effective creation of a genuinely unsettling atmosphere. It successfully delivers a grim, street-level thriller experience. However, it loses significant points for its often exploitative handling of sensitive subjects, reliance on uncomfortable stereotypes, and a general layer of sleaze that can be hard to stomach. It’s a potent, memorable film for specific reasons, but deeply flawed and certainly not for everyone.

Final Thought: This is the kind of tape you might have rented on a dare, expecting routine action, only to be confronted with something far bleaker – a stark reminder that sometimes, the "forbidden subjects" explored in cinema leave the deepest, darkest marks.