Okay, let's settle in. Dim the lights, maybe pour yourself something comforting. Remember pulling that slightly oversized clamshell case off the shelf at the video store? The cover art for Farewell to the King (1989) hinted at epic adventure, maybe something akin to The Man Who Would Be King, but what awaited inside was... different. More challenging, perhaps. More haunted. It’s one of those films that didn't quite explode at the box office but burrowed its way into the minds of those who gave it a chance on trusty VHS.

Directed by the singular John Milius – a filmmaker forever drawn to mythic figures and codes of honor, who gave us the raw power of Conan the Barbarian (1982) and the stark survival of Red Dawn (1984) – this film feels deeply personal. It's adapted from Pierre Schoendoerffer's 1969 novel L'Adieu au Roi, and you can sense Milius, who famously co-wrote Apocalypse Now (1979), returning to the crucible of war and the jungle, but exploring it from a fascinatingly altered perspective.

A Kingdom Forged in Escape

The premise itself is pure high-concept pulp, elevated by the execution: American Army Sergeant Learoyd (Nick Nolte) deserts during the Pacific campaign of World War II after witnessing the horrors of the Bataan Death March. He washes ashore in Borneo, is adopted by a tribe of headhunters, and through sheer will and perhaps a touch of madness, becomes their king – tattooed, revered, seemingly having shed his old self entirely. His isolated kingdom is violently disrupted when British Captain Fairbourne (Nigel Havers) arrives, seeking Learoyd’s tribal army to fight the invading Japanese forces.

What unfolds isn't just a war film, though battles certainly erupt. It's a profound meditation on identity, leadership, and the seductive, dangerous allure of escaping civilization only to recreate its power structures, albeit in a different form. Does Learoyd truly escape his past, or merely reshape it in a new, wilder context? That question hangs heavy in the humid jungle air throughout the film.

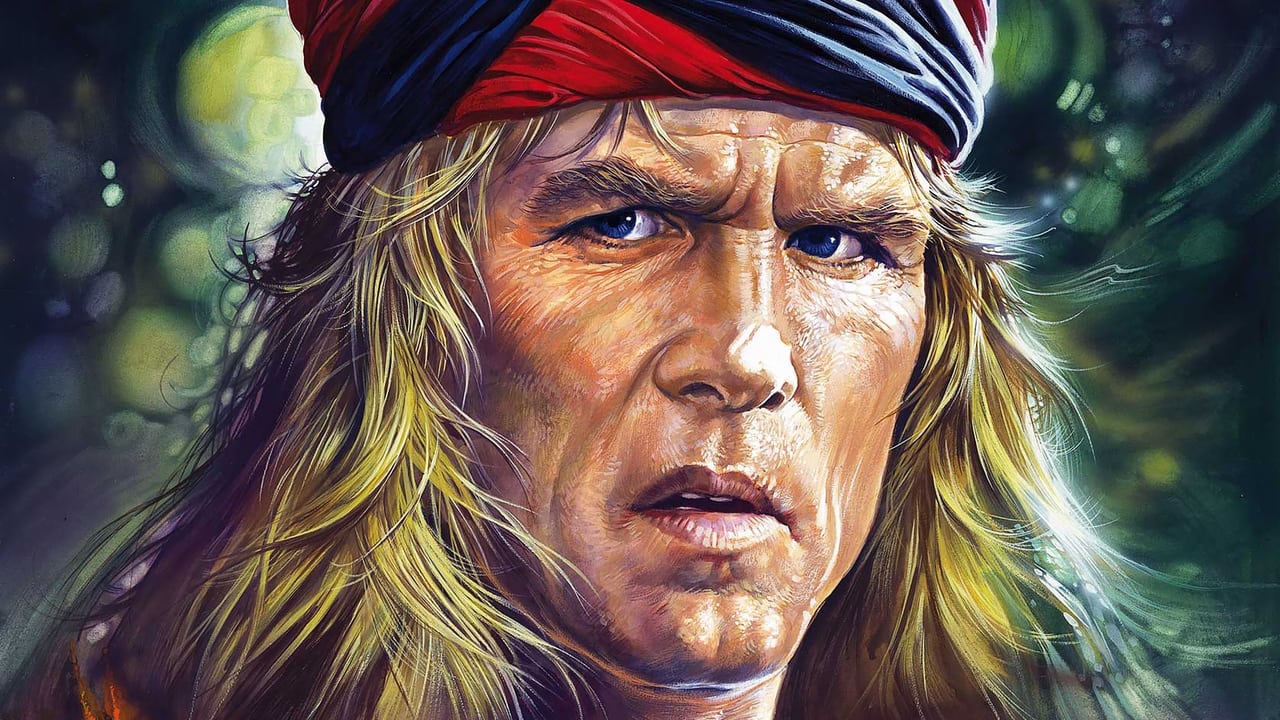

Nolte's Primal Transformation

At the absolute center of this maelstrom is Nick Nolte. Fresh off acclaimed roles in films like 48 Hrs. (1982) and Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986), Nolte throws himself into Learoyd with ferocious commitment. It’s more than just the physical transformation – the weathered skin, the tribal markings, the palpable sense of someone who has lived hard amongst nature. He embodies the character’s internal conflict: the lingering echoes of his American past clashing with the responsibilities and the sheer strangeness of his present kingship. There’s a weariness in his eyes even amidst the power he wields, a sense that his escape might be just another kind of trap. It's a raw, often uncomfortable performance, but utterly magnetic. Watching him, you believe this man could command loyalty and fear in equal measure.

Milius's Vision, Lush and Brutal

Milius brings his characteristic muscularity to the direction, but there’s also a surprising lyricism here. Filming on location in Sarawak, Malaysia (Borneo), was clearly essential. The verdant, oppressive beauty of the jungle isn't just a backdrop; it's practically a character. You feel the heat, the humidity, the sense of isolation that could drive a man to such extremes. This authenticity grounds the potentially fantastical story. Milius had reportedly wanted to make this film for over a decade, viewing it as a thematic cousin to Apocalypse Now, exploring the 'king' figure born from the chaos of war. The logistics of filming such an ambitious picture deep in the jungle must have been immense, echoing the very challenges faced by the characters.

The score by the great Basil Poledouris, who collaborated so effectively with Milius on Conan, adds another layer of epic sweep and emotional depth. It captures both the grandeur of Learoyd's unlikely kingdom and the underlying melancholy of his story. The clash between Learoyd’s raw, instinctual rule and Fairbourne’s more buttoned-down British military approach, personified well by Nigel Havers, forms the film's ideological spine. Their debates about duty, loyalty, and the 'right' way to fight a war feel potent.

More Than Just Adventure

Perhaps Farewell to the King struggled commercially (reportedly earning significantly less than its $16 million budget) because it defied easy categorization. It wasn't simply an action-packed war movie, nor was it purely an introspective drama. It dared to blend visceral combat sequences with philosophical questions about colonialism, the nature of power, and the very definition of 'civilization'. It asks: Can one truly leave the world behind? And if you build a new world, are you destined to repeat the mistakes of the old one? These aren't easy questions, and the film doesn't offer simple answers. It leaves you pondering Learoyd's fate and the weight of his choices long after the credits roll.

The supporting cast, including Frank McRae as Learoyd's loyal lieutenant Tenga, adds texture and depth to the tribal world. While some aspects might feel dated through a modern lens regarding cultural representation, the film seems genuinely interested in Learoyd's complex relationship with the people he leads, rather than treating them as mere props.

Final Reflection

Rewatching Farewell to the King now, decades after first encountering it on VHS, its ambition feels even more striking. It’s a complex, sometimes uneven film, but its willingness to grapple with big ideas within an epic adventure framework is commendable. Nolte's performance remains a towering achievement, and the sheer atmosphere generated by the location filming and Milius's direction is undeniable. It’s a film that truly transports you, even if the destination is uncomfortable and morally ambiguous. It’s the kind of movie that video stores allowed us to discover – something grander and stranger than the multiplexes might have offered that week.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: The film earns this score for its powerful central performance by Nolte, Milius's ambitious direction, the stunning location work creating an immersive atmosphere, and its willingness to explore complex themes beyond typical genre fare. It loses some points for occasional pacing lulls and perhaps not fully resolving some of its intricate ideas, contributing to its niche appeal rather than mainstream success. Still, its strengths significantly outweigh its weaknesses.

It lingers, this image of a man caught between worlds, a king forged in desperation. What does it truly mean to lead, to belong, or to escape? Farewell to the King doesn't just tell a story; it poses questions that echo long after the jungle falls silent.