The air hangs thick and humid, smelling of sweat, desperation, and stale concrete. There's a constant low hum of background noise – indistinct shouting, clanging metal, the scrape of boots on the floor – that sinks under your skin and stays there. This isn't just a movie location; it's a pressure cooker, filmed with such raw, suffocating realism by director Ringo Lam that you can almost feel the grime settling on you through the television screen. Welcome to Prison on Fire (監獄風雲), a film that doesn't just depict prison life; it throws you headfirst into the inferno.

Into the Crucible

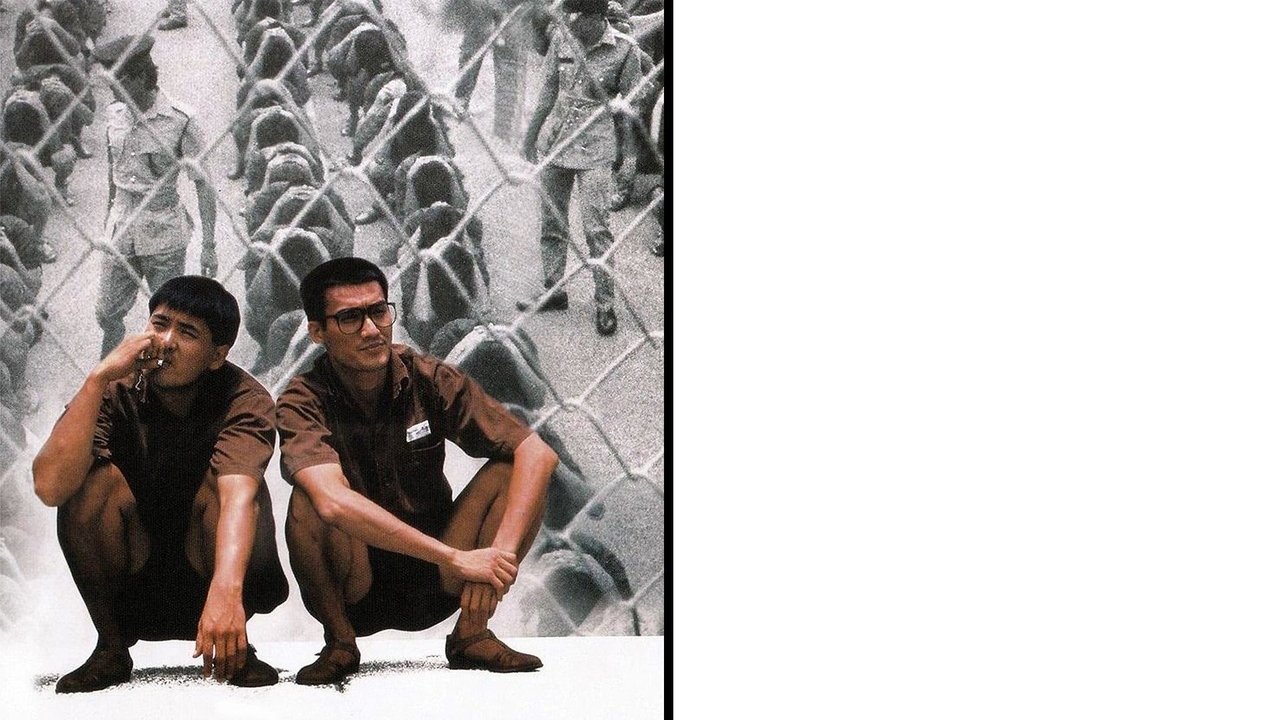

From the opening moments, as the naive Lo Ka-yiu (Tony Leung Ka-fai, in a performance leagues away from his sometimes suave later roles) arrives, bewildered and terrified after a manslaughter charge, Lam establishes an atmosphere of pervasive dread. This isn't the somewhat romanticized or action-packed prison of many Western films. This is a brutal ecosystem governed by predatory gangs, simmering resentments, and the casual cruelty of corrupt guards. Leung perfectly captures the vulnerability of an ordinary man thrust into extraordinary, terrifying circumstances. You see the hope drain from his eyes almost immediately, replaced by the constant, gnawing fear of survival.

Into this steps Chung Tin-ching, played by the inimitable Chow Yun-fat. Already a megastar thanks to John Woo's A Better Tomorrow (1986), Chow here dials back the heroic bloodshed theatrics for something more grounded, yet equally magnetic. Ching is a seasoned inmate, cynical yet fiercely loyal, navigating the prison's treacherous currents with a weary resilience. He becomes Yiu's reluctant protector and guide, their burgeoning friendship a fragile shield against the surrounding darkness. Chow’s performance is a masterclass in contained charisma – moments of humor and warmth flash through, but always underscored by the grim reality of their situation. He's seen it all, and the weariness is etched onto his face.

The Devil Wears a Uniform

No descent into cinematic hell is complete without a truly terrifying antagonist, and Prison on Fire delivers one for the ages in Officer "Scarface" Hung, played with chilling sadism by Roy Cheung. This role effectively launched Cheung's career as one of Hong Kong cinema's most iconic villains. Hung isn't just corrupt; he actively relishes his power, manipulating inmates, instigating violence, and embodying the systemic rot that makes the prison unbearable. There's a predatory stillness to him, a glint in his eye that promises pain. Lam reportedly pushed his actors hard for realism, and Cheung’s portrayal feels terrifyingly authentic – a figure of absolute, unchecked authority gone rotten. Does any other 80s movie villain radiate such casual menace?

Ringo Lam's Unflinching Vision

Released the same year as his equally influential City on Fire (the gritty realism of which famously inspired Quentin Tarantino), Ringo Lam cemented his reputation as a master of Hong Kong's darker, more realistic wave of crime cinema. Prison on Fire showcases his signature style: handheld camerawork that feels almost documentary-like, claustrophobic framing that emphasizes the lack of escape, and sudden, shocking bursts of violence that feel ragged and desperate, not stylized. The fight scenes aren't choreographed ballets; they're ugly, chaotic struggles for survival, often ending abruptly and brutally. It’s said Lam favoured practical effects and real reactions, sometimes putting his cast in genuinely uncomfortable situations to capture that raw edge – a stark contrast to the more polished productions emerging elsewhere. The film reportedly cost around HK$8 million and pulled in over HK$31 million at the Hong Kong box office, proving audiences were ready for this level of intensity.

More Than Just Walls

Beneath the surface layer of violence and institutional decay, Prison on Fire explores potent themes of brotherhood, injustice, and the struggle to retain humanity under crushing pressure. The bond between Ching and Yiu forms the emotional core, a testament to loyalty in a place designed to break spirits. The film doesn't offer easy answers or triumphant victories. It presents a bleak, cyclical world where acts of defiance often lead to further suffering, yet the impulse towards connection and solidarity persists. Watching it back then on a fuzzy VHS tape, maybe a copy passed between friends, the film’s raw power felt utterly distinct, a window into a harsher cinematic reality than Hollywood typically offered. It felt dangerous.

Lasting Echoes

Prison on Fire wasn't just a hit; it became a benchmark for the prison genre in Hong Kong cinema, spawning a sequel (Prison on Fire II, 1991, also directed by Lam and starring Chow) and countless imitators. Its influence can be felt in the wave of gritty crime thrillers that followed. While some aspects might feel dated to modern eyes – the specific slang, perhaps some of the melodrama – the core intensity, the powerhouse performances, and Lam's suffocating atmosphere remain incredibly potent. It’s a film that grabs you by the throat and refuses to let go, leaving you feeling bruised and unsettled long after the credits roll. It’s a stark reminder of the power of Hong Kong cinema in its prime, unafraid to stare into the abyss.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

The rating reflects the film's sheer visceral impact, its unflinching realism, the career-defining performances from Chow Yun-fat and Roy Cheung, and Ringo Lam’s masterful creation of a suffocating, dread-filled atmosphere. It loses a single point perhaps only for moments where the melodrama common in HK cinema of the era slightly strains credulity, but its power is undeniable.

Prison on Fire remains a brutal, essential piece of 80s Hong Kong cinema – a film that truly feels like contraband smuggled out from behind bars, documenting the darkness with a raw, unforgettable honesty. It’s not an easy watch, but it’s a necessary one for anyone serious about the era's cinematic output.