The air hangs thick and damp, heavy with the smell of rain on concrete. It’s the kind of pervasive chill that seeps into your bones, much like the lingering unease left by Takashi Miike’s 1997 mood piece, Rainy Dog (Gokudô kuroshakai). Forget the gonzo extremes Miike would later become infamous for; this is something different. This is the second entry in his thematic Black Society Trilogy, a film steeped in alienation and the quiet desperation of displacement, filmed entirely on location in Taipei, Taiwan, adding an inescapable layer of authenticity to its protagonist's isolation. It feels less like a yakuza thriller and more like a slow, inevitable slide into a waterlogged abyss.

### An Exile Drenched in Melancholy

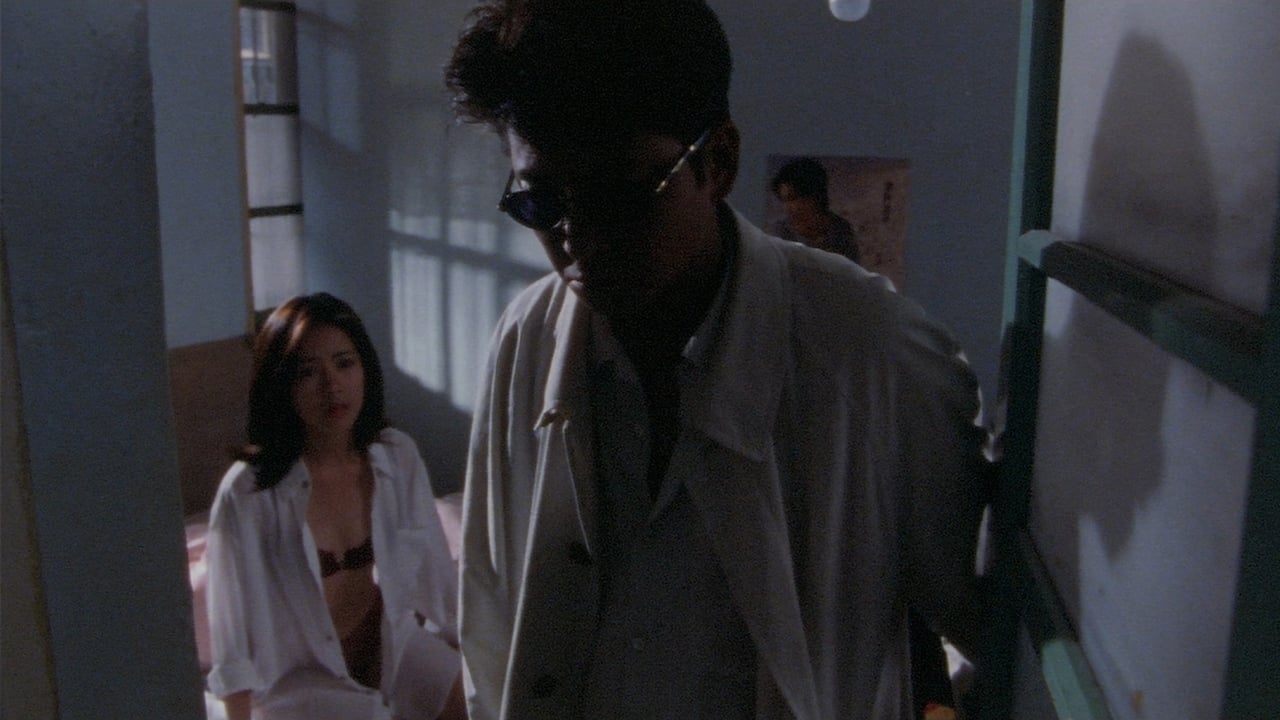

Our "hero," if you can call him that, is Yuji (the ever-reliable Show Aikawa, a frequent Miike collaborator), a Japanese yakuza exiled to Taiwan after taking the fall for his boss. He’s adrift, working low-level hits for local gangsters, barely communicating, living in a perpetually damp apartment under skies that seem to weep constantly. The film doesn't just show rain; it makes you feel it – the oppressive humidity, the slick streets, the way it mirrors Yuji’s own internal bleakness. Miike, even this relatively early in his prolific career (legend has it he was directing multiple films simultaneously around this period, a pace he somehow maintained), demonstrates a masterful control of atmosphere. The choice to shoot in Taipei wasn't just cosmetic; it was crucial, making Yuji’s otherness palpable in every frame. You sense his inability to connect, the language barrier amplifying his profound loneliness.

### An Unexpected Burden

The fragile equilibrium of Yuji's solitary existence is shattered when a woman appears, claiming he's the father of her mute son, Chen. She abandons the boy with him, adding an unexpected, unwanted responsibility to his already precarious life. The dynamic between the stoic, emotionally stunted Yuji and the silent, watchful Chen becomes the film's aching heart. There are no easy breakthroughs, no sudden heartwarming moments. Instead, we witness a tentative, awkward connection forming amidst the grime and violence of Yuji's world. Show Aikawa delivers a performance of remarkable restraint, conveying worlds of weariness and simmering violence through subtle glances and stiff body language. Young Xianmei Chen as the boy is equally compelling, his silence speaking volumes. Doesn't that silent bond feel more potent than any overwrought dialogue could?

### Grit Over Glamour

Unlike the stylized gangster epics some might associate with the genre, Rainy Dog is deliberately unglamorous. The violence, when it comes, is brutal but matter-of-fact, devoid of flashy choreography. It's clumsy, desperate, and often grimly sudden. Miike, working with screenwriter Seigo Inoue (who penned all three films in the trilogy), seems less interested in the mechanics of the criminal underworld and more in the human cost – the corrosive effects of exile, violence, and the struggle to find meaning in a life defined by killing. The production design reflects this perfectly; Taipei feels like a real, lived-in city, not a stylized movie set. It’s all peeling paint, neon reflecting on wet pavement, and cramped, dimly lit interiors.

One fascinating tidbit often mentioned about Miike's work, especially from this V-Cinema era (straight-to-video films often shot quickly and cheaply), is the sheer speed of production. While specific numbers for Rainy Dog are hard to pin down, it was part of a period where Miike was churning out multiple features a year, sometimes reportedly shooting films back-to-back with minimal prep. This frantic energy isn't always apparent on screen here; Rainy Dog feels more deliberate, more patient than some of his other works, but knowing the context adds another layer to appreciating the focused mood he achieved. It wasn't just about speed; it was about capturing a raw, immediate feeling, often born from necessity.

### Lingering Dampness

Rainy Dog isn't a film that offers easy answers or catharsis. It’s a slow burn, a character study wrapped in the guise of a crime film. It explores themes of identity, belonging (or lack thereof), and the faint possibility of redemption in a world that seems determined to crush it. It sits alongside Shinjuku Triad Society (1995) and Ley Lines (1999) as a powerful examination of Japanese characters adrift in foreign lands, disconnected from their roots and struggling to survive on the margins. These weren't the high-budget blockbusters filling multiplexes; finding a tape of something like Rainy Dog felt like unearthing a hidden gem, a grittier, more challenging experience than mainstream fare. It’s the kind of film that sticks with you, like the damp chill of that endless Taipei rain.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Rainy Dog earns its score through its masterful atmospheric control, Show Aikawa's deeply felt performance, and its poignant exploration of alienation. It's a deliberately paced film, and its bleakness might deter some, preventing a higher score. However, its gritty realism, emotional core, and importance within Takashi Miike's early filmography make it a standout piece of 90s Japanese cinema.

Final Thought: More than just a yakuza flick, Rainy Dog is a haunting portrait of exile that uses its setting and relentless atmosphere to create a profound sense of melancholy, proving early on that Takashi Miike was capable of far more than just shock value. It’s a film that feels remarkably grounded and deeply human, even amidst the violence.