The electric hum of a poorly grounded neon sign against the relentless California sun – that’s the contradictory image that often springs to mind when I think of 8 Million Ways to Die. It’s a film bathed in the harsh L.A. light, yet saturated with a deep, lingering darkness. Released in 1986, this wasn't just another crime thriller gathering dust on the video store shelves; it was a collision of immense talent navigating a notoriously troubled production, leaving behind a film that’s as fascinatingly fractured as its central character. Slipping this tape into the VCR back in the day often felt like uncovering something potent, maybe even a little dangerous.

Sun-Bleached Corruption

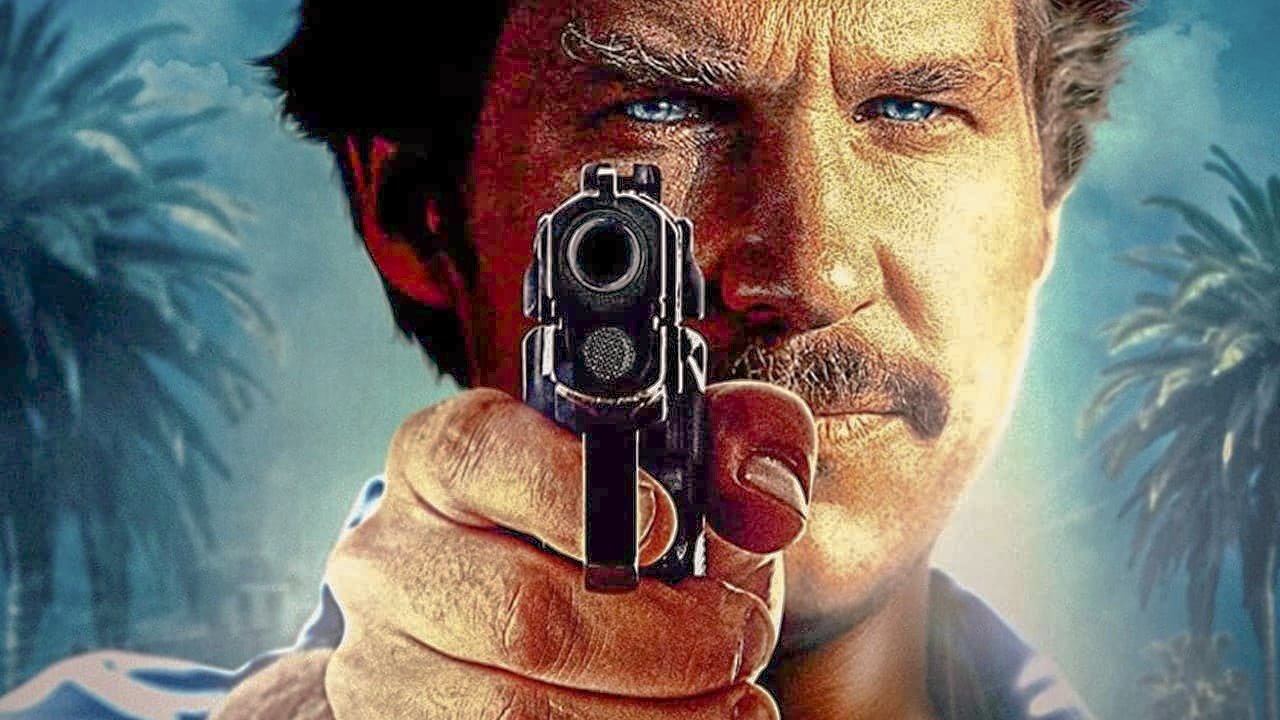

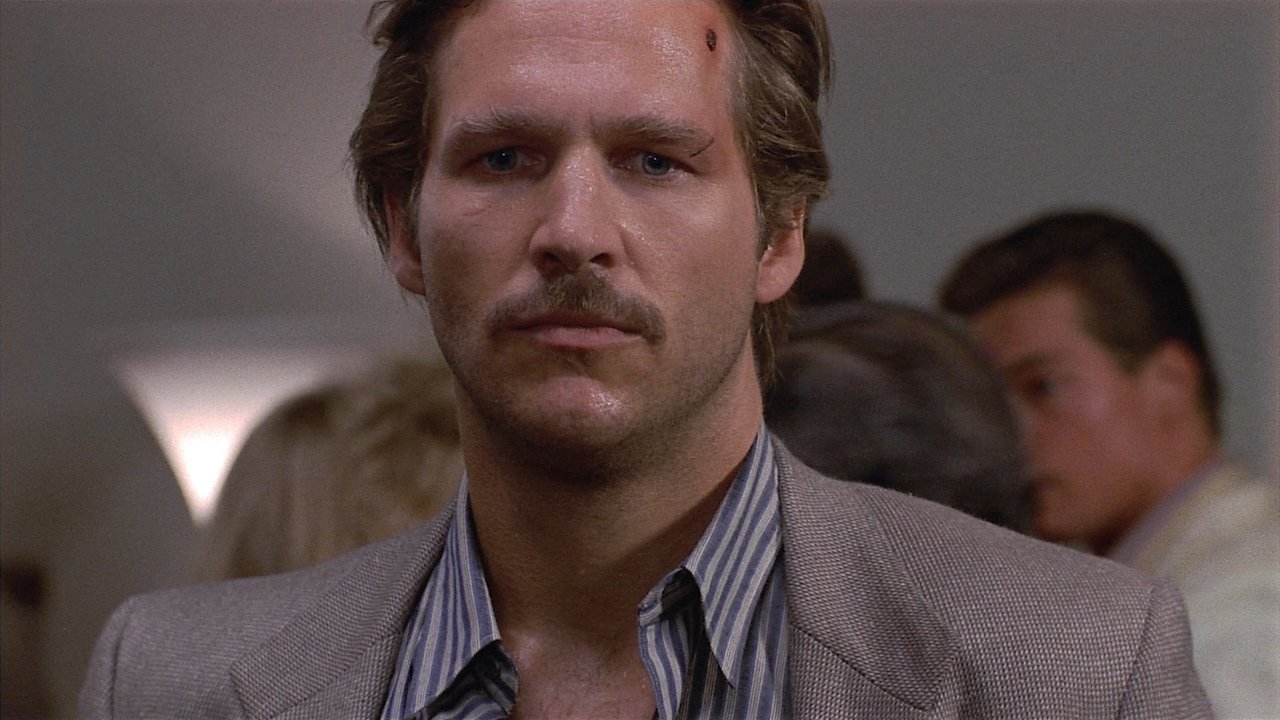

At its core, the film follows Matt Scudder, played with a raw, frayed-nerve intensity by Jeff Bridges. Scudder is a cop, or rather, an ex-cop from the L.A. County Sheriff's Department, whose career and life have been derailed by alcoholism following a justified but traumatic shooting. He’s adrift, attending AA meetings, trying to piece himself back together when he gets reluctantly pulled into the orbit of Sunny (a vulnerable yet resilient Rosanna Arquette), a high-end call girl desperate to escape her life and the clutches of her charismatic but menacing handler, Angel Maldonado. And who plays Angel? A young, magnetic Andy Garcia, radiating star power in one of his earliest prominent roles, perfectly capturing that blend of charm and chilling volatility. The plot unfolds from there, a tangled web of drugs, money, betrayal, and Scudder’s own desperate fight for sobriety amidst the moral decay.

A Troubled Soul in a Troubled Production

You can’t really talk about 8 Million Ways to Die without acknowledging the chaos behind the scenes, and honestly, knowing it deepens the viewing experience. Esteemed director Hal Ashby, the visionary behind classics like Harold and Maude (1971) and Being There (1979), was at the helm, but reportedly clashed mightily with producer Dino De Laurentiis. Add screenwriting credits that include heavyweights Oliver Stone (who apparently penned a much darker, bleaker initial draft) and Robert Towne (Chinatown’s scribe), and you have a recipe for either genius or combustion. Here, it feels like a bit of both.

The stories are legendary among film buffs: Ashby delivering a sprawling, unconventional first cut, the producers panicking, Ashby allegedly being locked out of the editing room, and the film being significantly recut by others. It’s a production saga almost as dramatic as the film itself. And you feel it. There’s an undeniable choppiness at times, moments where the narrative seems to jump or resolutions feel abrupt. Yet, paradoxically, Ashby’s signature sensitivity still permeates the film, especially in the quieter moments focused on Scudder’s struggle. Knowing this context doesn't excuse the flaws, but it transforms the film from merely uneven into a compelling artifact of creative conflict – a glimpse of the brilliant, possibly bleaker film that might have been. The film cost a hefty $18 million (around $48 million today) but sadly didn't recoup its budget, becoming one of those fascinating commercial failures that finds its audience later, often on home video.

Raw Nerves and Neon Nights

Despite the production turmoil, the performances are what truly anchor 8 Million Ways to Die. Jeff Bridges, always an actor of incredible authenticity, is simply outstanding as Scudder. He doesn't just play drunk; he embodies the exhausting, moment-to-moment battle of early sobriety – the shakes, the paranoia, the vulnerability hidden beneath a veneer of tough-guy resignation. It’s a raw, unvarnished performance that feels painfully real. You see the desperation in his eyes as he pours booze down the sink, the self-loathing, and the flickering hope for something better. It’s a testament to Bridges' skill that Scudder remains sympathetic, even when making questionable choices.

Rosanna Arquette matches him with a performance that balances fragility and street smarts. Sunny isn't just a damsel in distress; she’s caught in a dangerous game, trying to play her own hand. And Andy Garcia? It's easy to see why this role helped put him on the map. His Angel Maldonado is smooth, stylish, and utterly terrifying, often in the same breath. He possesses a coiled intensity that makes every scene he’s in crackle with tension. These central performances provide the film's solid, unwavering core.

An Imperfect Gem from the Neon Era

Watching it now, the film feels quintessentially mid-80s L.A. noir – the synth-heavy score by James Newton Howard (in one of his earlier film composing efforts), the slightly oversized suits, the pervasive sense of sun-drenched melancholy. It captures a specific mood, a time when crime thrillers could be gritty and character-driven, even if the plot mechanics occasionally sputtered. Does the film fully realize the potential hinted at by its pedigree of talent? Perhaps not entirely. The structural issues stemming from the post-production battles are undeniable.

But does it linger? Absolutely. The atmosphere Ashby conjures, the unease that permeates even the brightest California day, and the sheer power of Bridges' central performance make it far more memorable than many slicker, more conventionally "perfect" thrillers of the era. It’s a film that asks uncomfortable questions about addiction, the possibility of redemption in a fallen world, and the compromises we make to survive. What stays with you isn't necessarily the intricate plotting, but the feeling – the sweaty palms, the desperation, the ghosts haunting the palm tree-lined streets.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable strengths – primarily the powerhouse performances from Bridges, Arquette, and Garcia, and the palpable, gritty atmosphere created by Ashby despite the production nightmare. It captures the dark heart of 80s L.A. noir effectively. However, the rating is tempered by the noticeable narrative inconsistencies and tonal shifts, clear battle scars from its notoriously troubled editing process, which prevent it from reaching the masterpiece status its talent roster might suggest.

It remains a potent, if flawed, piece of 80s cinema – a must-watch for fans of Jeff Bridges, neo-noir, or anyone fascinated by those moments when Hollywood chaos inadvertently creates something uniquely compelling. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most interesting stories aren't just the ones on screen, but the ones behind it, leaving us with a film that, much like its protagonist, is bruised but still standing.