It’s a strange thing, the path from youthful idealism to treason. Not the calculated move of a hardened ideologue, but the slow, almost accidental slide born of disillusionment. That's the unsettling territory explored in John Schlesinger's 1985 film, The Falcon and the Snowman, a movie that sticks with you long after the VCR whirs to a stop, leaving behind a residue of unease and a raft of uncomfortable questions. It wasn't your typical Cold War thriller; there were no suave super-spies, just two young, privileged Californian guys stumbling into espionage with devastating consequences.

Based on Robert Lindsey's non-fiction book detailing the real-life exploits of Christopher Boyce and Daulton Lee, the film feels chillingly plausible precisely because it avoids grand theatrics. What makes it so compelling, and perhaps even more relevant today, is its exploration of how easily apathy and a vague sense of grievance can curdle into something far more dangerous.

Two Sides of Betrayal

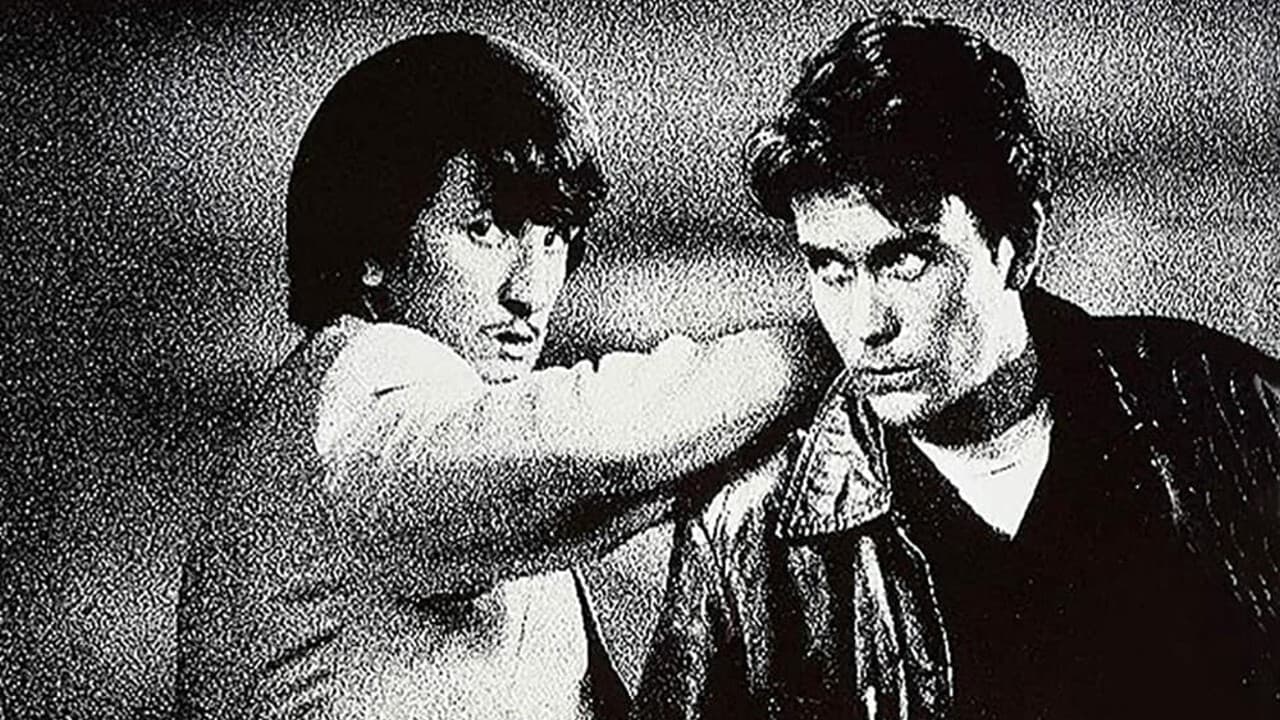

At the heart of the film are two astonishingly good performances that feel less like acting and more like captured behavior. Timothy Hutton, fresh off his Oscar win for Ordinary People, plays Christopher Boyce (the "Falcon," an enthusiast of falconry). He's the disillusioned seminarian drop-out who lands a job with a defense contractor, gaining access to highly classified CIA documents. Hutton embodies Boyce's quiet intelligence and simmering resentment. You see the dawning horror and cynical disgust in his eyes as he reads messages detailing US interference in foreign governments (specifically Australia, a detail that caused quite a stir down under upon the film's release). His decision to sell secrets to the Soviets feels less like a political statement and more like a passive-aggressive act of rebellion against a system he suddenly despises, a misplaced lashing out by someone who feels fundamentally betrayed. It’s a performance built on subtle shifts and internalized turmoil.

Contrast this with Sean Penn as Andrew Daulton Lee (the "Snowman," for his drug dealing). Penn, already showing the ferocious intensity that would define his career, is utterly magnetic as the reckless, coke-snorting childhood friend Boyce enlists as his courier. Lee isn't driven by ideology; he's driven by desperation, greed, and a pathetic need for validation. Penn plays him as a bundle of exposed nerves and misplaced swagger, a small-time hustler suddenly playing in a league far beyond his comprehension. The scenes of him navigating the Soviet embassy in Mexico City, fueled by drugs and paranoia, are squirm-inducing masterpieces of controlled chaos. It's a tragically pathetic portrait, yet Penn never lets Lee become a caricature. You see the scared kid beneath the bluster. Apparently, Penn stayed in character quite intensely on set, adding to the unpredictable energy Lee brings to the screen.

The Mundanity of Treason

John Schlesinger, a director known for his character-driven dramas like Midnight Cowboy and Marathon Man, brings a grounded, almost detached perspective to the proceedings. He’s less interested in the mechanics of spycraft and more focused on the psychological unraveling of his protagonists. The film masterfully captures the sun-drenched, aimless privilege of Southern California juxtaposed against the drab, paranoia-infused world of Cold War espionage. There’s a deliberate lack of glamour; the meetings are clumsy, the motives murky, the consequences tragically real. This isn't James Bond; it's messy, stupid, and ultimately, deeply sad.

The screenplay, adapted by Steven Zaillian (who would later pen Schindler's List), skillfully translates Lindsey's detailed book, preserving the core ambiguity. Was Boyce a misguided patriot exposing government overreach, or a naive traitor? Was Lee just a hapless drug addict caught in the crossfire, or a willing participant driven by greed? The film wisely refuses easy answers, forcing us to grapple with the uncomfortable humanity of its central figures. It challenges the viewer to consider what lines they might cross when faced with disillusionment or desperation.

Echoes from the Cold War Bunker

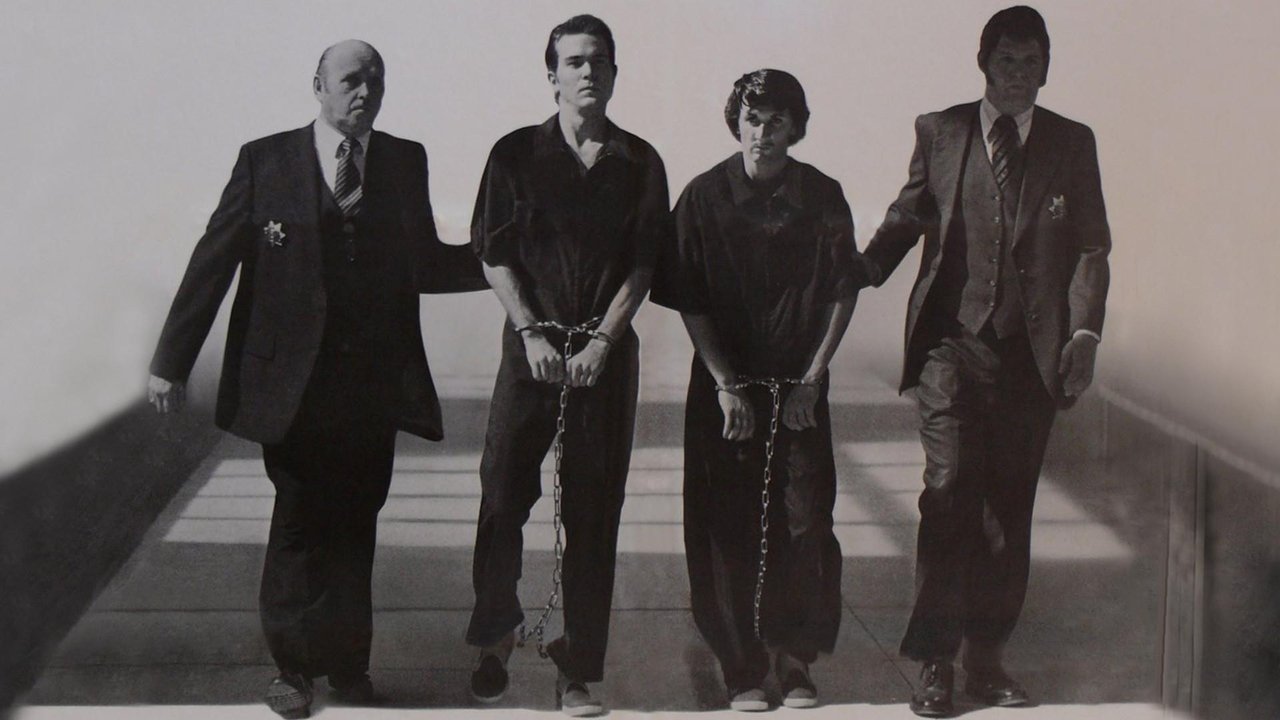

Watching The Falcon and the Snowman today, decades removed from the specific Cold War anxieties it depicts, its power remains undiminished. The film cost around $12 million to make and performed moderately at the box office, perhaps because its downbeat tone and moral complexity weren't what audiences always sought in the escapist mid-80s. Yet, its themes resonate powerfully. The idea of disillusionment with institutions, the ease with which secrets can be compromised (albeit Boyce handled paper documents, not digital files!), and the destructive potential of unchecked cynicism feel starkly contemporary.

One fascinating production detail involves the iconic score by the Pat Metheny Group, featuring the haunting theme "This Is Not America" sung by David Bowie. It perfectly encapsulates the film's mood – a sense of alienation and dreamlike detachment from the supposed American ideal. It’s a score that doesn’t just accompany the film; it deepens its emotional landscape. Interestingly, the real Christopher Boyce initially refused to cooperate with the filmmakers, only relenting later, adding another layer to the complex relationship between reality and its cinematic portrayal. He was eventually paroled in 2002, while Lee was paroled in 1998. Their story serves as a stark cautionary tale, stripped of any romanticism.

Final Thoughts

The Falcon and the Snowman isn't an easy watch. It lacks clear heroes and satisfying resolutions. But it’s precisely this ambiguity, anchored by Hutton and Penn's superb performances and Schlesinger’s assured direction, that makes it such a compelling and enduring piece of 80s cinema. It digs under the surface of headlines about espionage to find the flawed, relatable human beings swept up in events larger than themselves. It asks us to consider the quiet ways idealism can die and the unpredictable paths betrayal can take. Doesn't that uncomfortable truth about human fallibility still linger today?

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's powerful performances, its intelligent and nuanced handling of complex themes, Schlesinger's masterful direction, and its chillingly effective atmosphere. While perhaps lacking the thrills of conventional spy fare, its psychological depth and grounding in reality make it a standout drama of the era. It's a thoughtful, unsettling film that truly earns its place as more than just a footnote in Cold War cinema.