Okay, fellow travellers through time and magnetic tape, let’s dim the lights, maybe pour something contemplative, and settle in. Tonight, we’re pulling a rarer gem from the shelves, one that likely sat in the ‘Foreign Films’ section of only the most dedicated video stores, radiating a quiet intensity that belied its simple cover art. I’m talking about Krzysztof Kieślowski's 1985 Polish film, No End (Bez końca). This isn't your typical Friday night rental fodder; it’s a film that settles into your bones, a haunting whisper from a specific time and place that somehow feels universally resonant, especially when revisited decades later.

I distinctly remember the heft of this particular tape, finding it almost by accident, sandwiched between perhaps more accessible European titles. There was little fanfare, no booming trailer preceding it on other rentals. It was a discovery, and watching it felt like eavesdropping on profoundly private grief and simmering political tension, all filtered through the static hum of the VCR and the soft glow of the CRT.

A Ghostly Gaze on Grief and Governance

No End plunges us into the chilly reality of Poland shortly after the official lifting of Martial Law, though the air remains thick with its oppressive legacy. The film introduces us to Ula (Grażyna Szapołowska), a translator reeling from the sudden death of her husband, Antek, a passionate defence lawyer. But here’s the turn that elevates it beyond a simple drama: Antek is still present, unseen, unheard, a spectral observer tethered to the world he’s left behind. He watches Ula navigate her suffocating grief, her moments of quiet despair, her fumbling attempts to find solace, even considering consulting a hypnotist to reconnect. Simultaneously, he observes the continuation of a crucial political trial he was handling – the defence of a worker accused of organizing strikes – now taken over by his aging, weary mentor, Labrador (Aleksander Bardini).

This dual focus, viewed through the impotent eyes of the deceased, creates a unique and deeply melancholic atmosphere. Antek cannot intervene, only witness. Doesn't this ghostly perspective mirror the feeling of helplessness many felt under the regime, or indeed, the helplessness we sometimes feel in the face of overwhelming personal loss? It’s a powerful, unsettling conceit.

The Weight of Performance

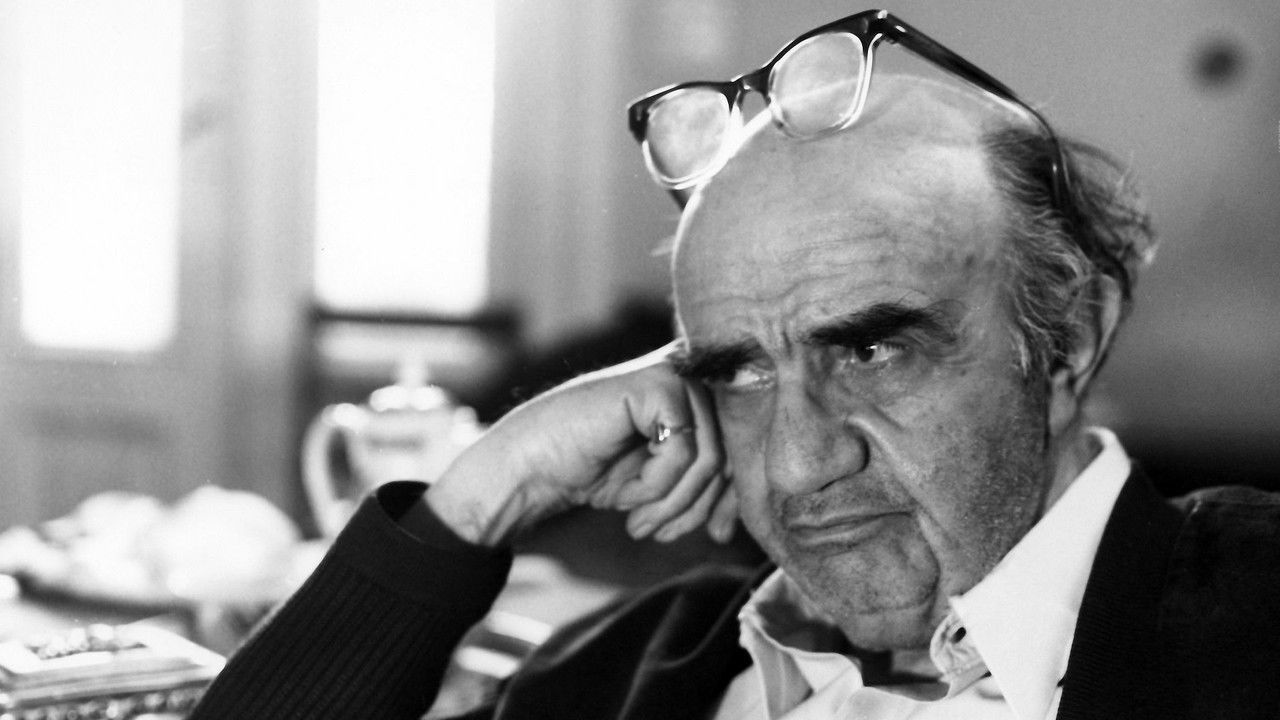

What truly anchors No End is the raw authenticity of its performances. Grażyna Szapołowska delivers a masterful portrayal of Ula's grief. It's not histrionic; it's visceral, deeply internalized. We see it in the slump of her shoulders, the vacant stare, the sudden bursts of desperate action followed by crushing inertia. Kieślowski’s camera often holds on her face, allowing us to map the complex terrain of her sorrow. It’s a performance that feels achingly true, capturing the disorientation and profound loneliness of losing one's anchor.

Equally compelling is Aleksander Bardini as Labrador. He embodies the weariness of an older generation, clinging to ideals within a compromised system. His interactions, particularly with Joanna (Maria Pakulnis), the defendant's resolute wife, reveal the subtle negotiations and moral tightropes walked by those trying to maintain integrity in impossible circumstances.

Whispers of Dissent, Seeds of Collaboration

This film marks the first crucial collaboration between director Krzysztof Kieślowski and screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz, who was himself a lawyer. This partnership would, of course, go on to give us the monumental The Decalogue (1989), The Double Life of Veronique (1991), and the Three Colors trilogy (1993-1994). You can see the seeds of their later thematic preoccupations here: the profound impact of small choices, the invisible threads connecting disparate lives, the search for meaning in a morally complex world, and a burgeoning interest in the metaphysical. Piesiewicz's legal background lends the courtroom and political threads an undeniable authenticity, grounding the film's more ethereal elements.

Unsurprisingly, No End faced a difficult reception in Poland. Made during a period of intense political sensitivity, it drew criticism from both the government (for its bleak portrayal of the post-Martial Law reality) and Solidarity supporters (who felt it depicted compromises too readily). Kieślowski found himself caught in the crossfire, a testament to the film's challenging ambiguity. Finding this context now adds another layer to watching it – understanding the courage it took to make such an unvarnished film at that time.

The VHS Discovery: A Different Kind of Reward

Let's be honest, No End wasn't the kind of tape you grabbed for a pizza-and-beer movie night. Discovering it felt like unearthing something significant, something demanding. It required patience, attention, and maybe a willingness to sit with discomfort. In the pre-internet age, finding films like this often relied on chance, a recommendation from a clued-in video store clerk, or pure browsing persistence. It was a reminder that the shelves held more than just the latest blockbusters; they held windows into other worlds, other perspectives, challenging works that lingered long after the tape ejected. Does anyone else remember that quiet satisfaction of finding a truly different film tucked away on those shelves?

Lingering Resonance

No End is not an easy watch. Its pace is deliberate, its mood predominantly somber. The ghostly premise isn't used for scares but for philosophical reflection on connection, loss, and the continuity of life and struggle even after death. It’s a film that doesn’t offer easy answers, reflecting the complex reality it depicts. Kieślowski masterfully uses the mundane details of life – a dripping tap, a shared cigarette, the sterile environment of a courtroom – to underscore the profound emotional and political currents running beneath the surface.

Rating: 8.5/10

This rating reflects the film's artistic merit, its powerful performances (especially Szapołowska's), its historical significance as the start of a major filmmaking partnership, and its haunting, thought-provoking atmosphere. It’s a challenging piece, undeniably bleak, and its pacing requires commitment, preventing a perfect score for general 'rewatchability' in the typical VHS sense. However, its depth and artistry are undeniable. No End earns its high score not through flashy effects or action, but through its quiet intensity, its unflinching gaze into the human heart grappling with grief and oppression, and its status as a crucial, if initially overlooked, piece of 80s European cinema.

It leaves you contemplating the ties that bind us, living and dead, and the quiet struggles that unfold behind closed doors, long after the major headlines have faded. A truly potent discovery from the back shelves of VHS Heaven.