The signal cuts through the void like a shard of ice – a distress call from Morganthus, a planet shrouded in a silence more profound than mere emptiness. It’s a silence that screams. And answering that scream is the crew of the starship Quest, dispatched on a rescue mission that spirals into a confrontation not with an external alien menace, but with the festering darkness coiled within their own minds. Welcome, friends, to the grim spectacle of 1981's Galaxy of Terror (also known, fittingly perhaps, as Mindwarp: An Infinity of Terror).

Into the Corman Nebula

Let’s be clear: this isn't high-minded sci-fi pondering the human condition. This is pure, unadulterated Roger Corman exploitation cinema, birthed in the wake of Alien's monumental success and aiming squarely for the gut. Produced under Corman's New World Pictures banner on a shoestring budget (reportedly under $1 million, a pittance even then), Galaxy of Terror embraces its derivative nature but injects it with a particularly nasty, almost nihilistic energy. The plot is threadbare: investigate the crashed ship, encounter spooky phenomena, get picked off one by one. But the how of their demise is where the film finds its uniquely unsettling – and often controversial – identity.

The alien intelligence on Morganthus doesn't just hunt; it manifests. It plucks the deepest fears from the crew's subconscious and turns them into tangible, lethal realities. Claustrophobia becomes crushing walls, fear of the dark yields unseen assailants, and primal anxieties spawn grotesque monstrosities. It’s a concept ripe for psychological horror, though the execution often leans heavily into visceral, B-movie shocks rather than sustained dread. Yet, there's a raw power to this idea, a feeling that the very environment is psychically hostile, peeling back layers of sanity to reveal the terror beneath.

Monsters from the Id (and the Workshop)

This film is infamous, of course, for that scene. Yes, the giant maggot sequence involving Erin Moran (in a stark departure from her Happy Days image) remains one of the most notoriously uncomfortable moments in 80s genre filmmaking. It’s excessive, exploitative, and frankly difficult to watch – a moment born perhaps from Corman’s mandate to push boundaries, reportedly even against the wishes of some involved. It undeniably leaves a mark, though not necessarily the kind the filmmakers might have fully intended.

But beyond that singular shock, the film boasts a menagerie of practical creature effects, some surprisingly effective, others charmingly clunky. Remember the sheer physicality of those VHS-era monsters? There's a tactile grossness here – writhing tentacles, crystalline shards impaling flesh, and Sid Haig battling his own severed, possessed arm (a truly bizarre highlight showcasing Haig's inimitable screen presence). It’s a testament to the ingenuity forced by low budgets. And speaking of ingenuity, the production design and second unit direction bear the fingerprints of a young James Cameron, honing his craft before The Terminator launched him into the stratosphere. Legend has it Cameron, tasked with creating maggot effects for another scene, devised a system using electrified plates to make them writhe on cue – a classic example of low-budget problem-solving that defined this era of filmmaking. You can see hints of his later industrial, metallic aesthetic in the ship interiors and the ominous pyramid structure dominating the planet's surface.

Fear Factors

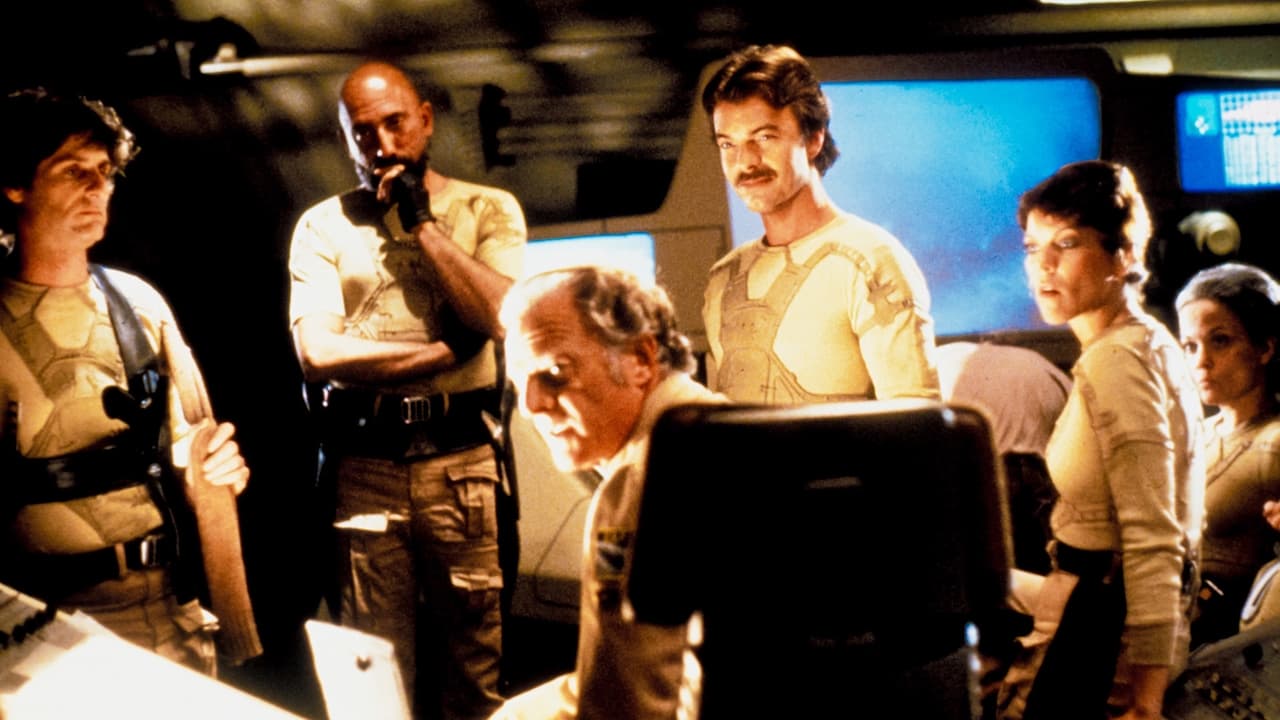

The cast does what they can with roles that are mostly archetypes designed for demise. Edward Albert plays the stoic hero, Ray Walston (My Favorite Martian) lends a touch of veteran class as the ship's cook, and we get early appearances from future horror staples Robert Englund and the aforementioned Sid Haig. They inhabit a world crafted by director Bruce D. Clark, who manages to wring some genuine atmosphere out of the desolate planetary landscapes and claustrophobic ship corridors. The score, a blend of electronic pulses and orchestral stings, effectively underscores the moments of tension and horror.

Yet, the film is undeniably uneven. The pacing sometimes flags between the set pieces, and the logic connecting the fears to their manifestations can feel arbitrary. It lurches between moments of genuine creepiness – the discovery of the skeletal remains aboard the derelict ship, the growing paranoia among the survivors – and outright schlock. Doesn’t that almost enhance the feeling, though? That sense of unease mixed with the slightly unhinged creativity born from limitation?

Echoes in the Void

Watching Galaxy of Terror now feels like excavating a specific stratum of cinematic history. It’s a time capsule of post-Alien anxiety, Corman-era opportunism, and the raw, sometimes messy, energy of practical effects work. I vividly recall encountering this tape on the shelves of my local video store, the lurid cover art promising horrors both cosmic and deeply personal. It delivered, albeit in a way that was often more baffling and grotesque than truly terrifying.

It’s not a masterpiece, not by a long shot. It’s often crude, occasionally nasty, and wears its influences on its sleeve. But there’s an undeniable fascination in its commitment to its grim premise and its place as a breeding ground for future talent. It represents a particular flavor of 80s sci-fi horror – one less polished, more visceral, and perhaps more willing to plumb uncomfortable depths, even if clumsily.

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's status as a notable, if flawed, piece of 80s exploitation horror. It gets points for its core concept, some memorably grotesque practical effects, its historical significance (Corman production, Cameron's early involvement, notable cast appearances), and its sheer bizarre energy. However, it loses points for its derivative plot, uneven execution, occasional lapse into pure schlock, and that one infamous, deeply problematic scene. It's a fascinating artifact, essential viewing for Corman enthusiasts and students of practical effects history, but its flaws are undeniable.

Final Thought: Galaxy of Terror might be rough around the edges, but it lingers – a strange, unsettling transmission from an era when sci-fi horror dared to get truly weird, even if it meant digging through the muck of our deepest fears. It’s a grimy, essential piece of the VHS puzzle.