How does one capture lightning in a bottle twice? That must have been the question weighing heavy on everyone involved in bringing A Chorus Line to the screen in 1985. The original stage musical wasn't just a hit; it was a phenomenon, a Pulitzer Prize-winner that stripped bare the vulnerable souls of dancers auditioning for a spot on the line. It was intimate, raw, performed on a minimalist stage where confessions felt like secrets whispered directly to the audience. Translating that specific, fragile magic to the inherently more literal medium of cinema, especially amidst the glossy expectations of mid-80s filmmaking, was perhaps an impossible task from the start.

The Weight of Expectation

The film, directed by the esteemed Sir Richard Attenborough – fresh off the monumental success of Gandhi (1982) – carried an almost crushing burden. The source material was revered, its score by Marvin Hamlisch (music) and Edward Kleban (lyrics) already legendary. Yet, Attenborough, perhaps surprisingly chosen over stage-savvier directors initially considered like Mike Nichols or Bob Fosse (who had declined years earlier), seemed determined to make it cinematic. This involved opening up the claustrophobic setting, adding elaborate fantasy sequences for some numbers ("Surprise, Surprise," "I Can Do That"), and attempting to give the aloof director Zach a more defined, even softened, presence.

Zach, Cassie, and the Line

As Zach, the demanding choreographer peering down from the darkness, Michael Douglas brings his signature intensity, yet the character feels somewhat diffused compared to his stage counterpart. The script by Arnold Schulman gives him more overt backstory and motivation, particularly concerning his past relationship with Cassie (Alyson Reed), the former principal dancer now desperately auditioning for the chorus. This central conflict provides the film's dramatic spine, and Reed, tasked with arguably the show's most iconic role and solo ("The Music and the Mirror"), pours immense heart and physical prowess into the performance. Her desperation feels palpable, a stark representation of talent colliding with the harsh realities of the industry. Yet, the chemistry between Douglas and Reed, while present, doesn't quite ignite the way their shared history suggests it should. A fascinating bit of trivia: the original Broadway Cassie, Donna McKechnie, whose performance was intrinsically tied to the role's creation, was passed over for the film, partly due to the desire for fresher faces or perceived 'movie' quality – a decision that still sparks debate among theatre fans.

The ensemble, the hopefuls on the line, deliver moments of truth. Standouts capture the essence of their characters' monologues – the humor in Val's "Dance: Ten; Looks: Three" (Audrey Landers), the poignant vulnerability of Paul's difficult confession (Cameron English), Diana's bittersweet longing in "Nothing" and defiant hope in "What I Did for Love" (Yamil Borges). However, Attenborough's handling of these intimate revelations sometimes feels caught between stage faithfulness and cinematic interpretation. The intercutting between monologue and audition footage can occasionally dilute the direct impact that made the stage show so electrifying.

Translating the Intangible

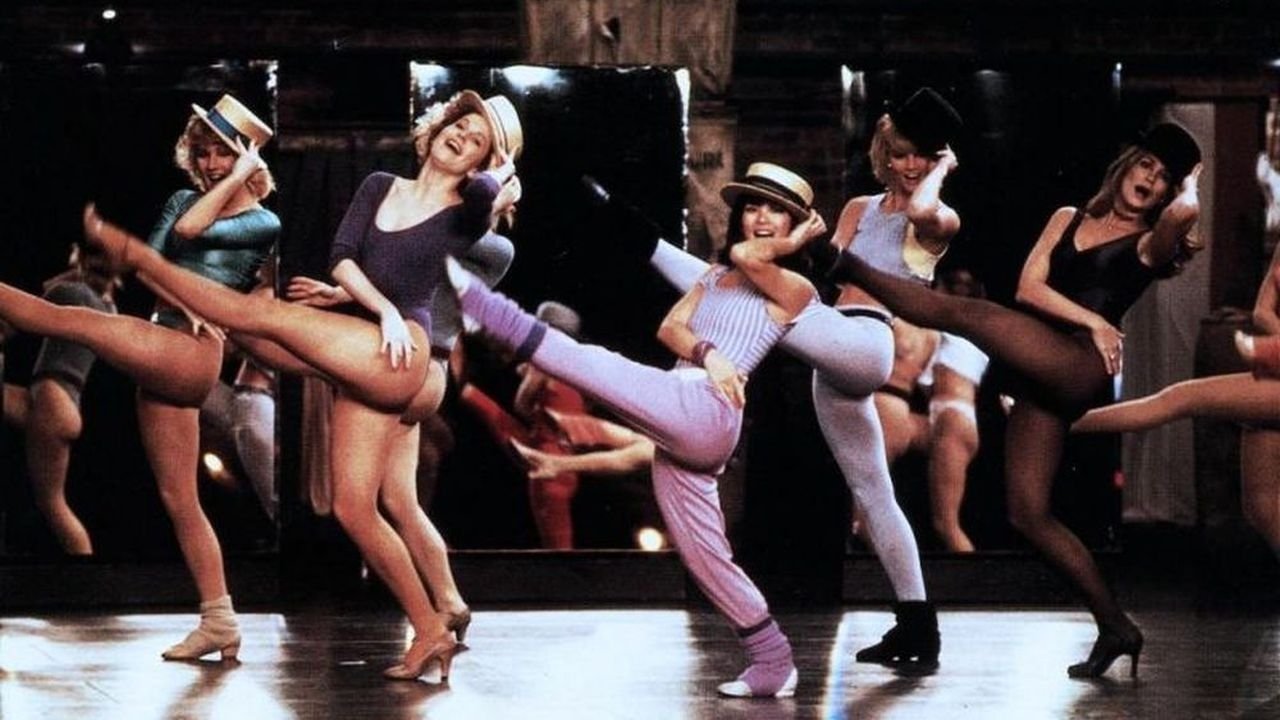

Where the film often struggles is in its attempt to visually "open up" the material. The stage show's power lay in its starkness – the bare stage, the mirrors, the line itself symbolizing both unity and ruthless competition. Attenborough and cinematographer Ronnie Taylor sometimes opt for more conventional coverage and staging, particularly during the dance numbers. While executed with professionalism, it occasionally lacks the raw, focused energy of the original concept. The score remains magnificent, of course, though some orchestrations feel distinctly '80s' in a way that slightly dates them compared to the timelessness of the stage arrangements.

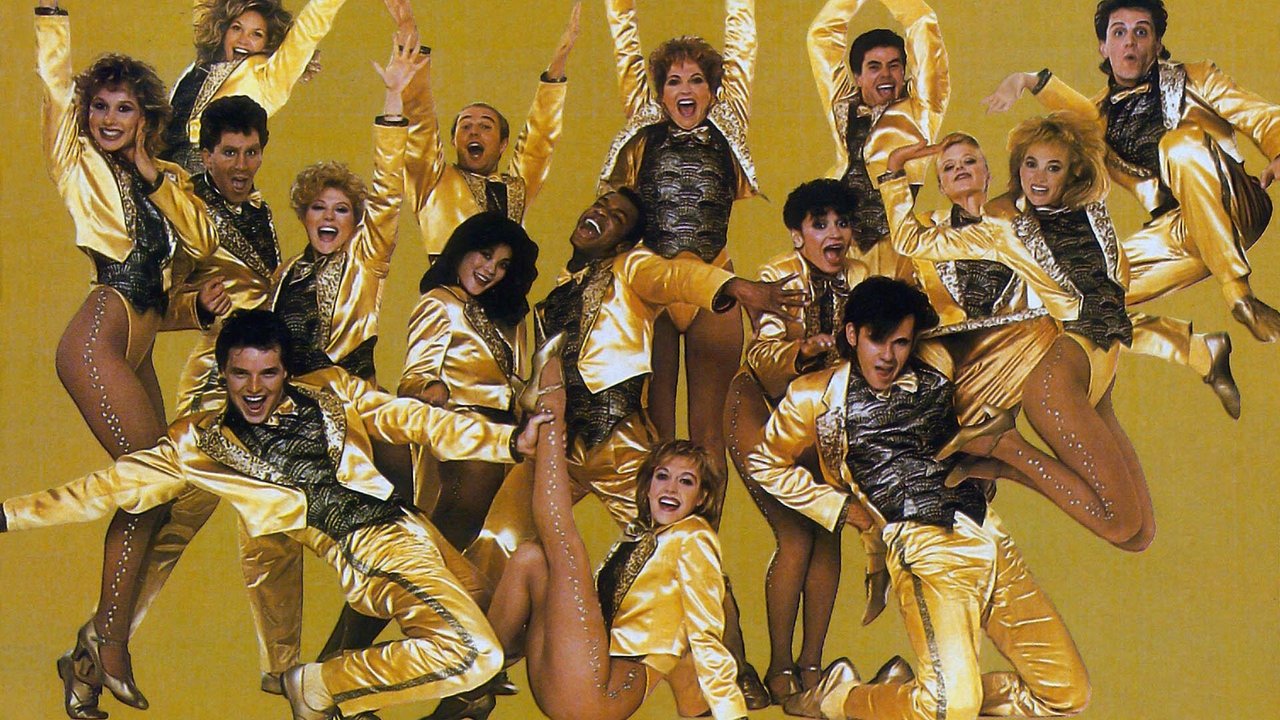

One of the most discussed – and for many, disappointing – choices was the finale. The stage show ends with the iconic, unified "One," where the chosen dancers, now identically costumed in gold, become an anonymous, dazzling machine – a powerful statement on individuality subsumed by the collective demands of the chorus. Attenborough opted for a more traditionally celebratory, curtain-call style ending, featuring individual bows in personalized variations of the gold costumes. While perhaps intended as a more uplifting cinematic close, it fundamentally alters the resonant, slightly chilling message of the original finale. This decision reportedly stemmed from Attenborough's feeling that the original ending was too downbeat for a film audience.

Retro Fun Facts

- The pressure to adapt the show was immense, reflected in its substantial $25 million budget (around $70 million today). Sadly, it didn't recoup that investment domestically, earning only about $14 million, making it a significant financial disappointment.

- Finding performers who were true "triple threats" (acting, singing, dancing) and possessed screen presence proved challenging. Extensive casting calls were held across the US.

- Attenborough's background was primarily in dramas and epics. Tackling a musical, especially one so reliant on theatrical convention, was a departure, and his approach reflects a certain unease with the form's specific language. He reportedly relied heavily on his choreographers, Jeffrey Hornaday and Michael Shawn, for the dance sequences.

Enduring Echoes

Does A Chorus Line the movie succeed? It's a question that likely divides viewers, especially those who hold the stage original dear. It's a handsomely produced film, featuring earnest performances and showcasing undeniably brilliant source material. Moments of genuine pathos and vulnerability shine through, particularly in the confessional monologues that remain the story's heart. The core themes – the relentless pursuit of artistic dreams, the sacrifices demanded, the search for identity within a demanding profession – still resonate. However, in striving for cinematic breadth, it sometimes loses the concentrated, intimate intensity that made the stage show a landmark. It feels less like a raw nerve exposed and more like a well-mounted, slightly sanitized interpretation.

Rating Justification: 6/10

A Chorus Line earns a 6 because it's a competent, often heartfelt, but ultimately compromised adaptation. The strength of the original songs and stories provides a solid foundation (preventing a lower score), and several performances, particularly Alyson Reed's, are genuinely moving. However, the film struggles to translate the unique theatricality and raw intimacy of the stage show. Attenborough's direction, while professional, feels somewhat conventional, and key artistic choices (like the altered ending and certain visual interpretations) dilute the source material's specific power. It captures elements of the musical's brilliance but fails to replicate its singular impact, leaving it feeling like a well-intentioned but ultimately flawed photograph of a theatrical masterpiece.

Final Thought: Perhaps the truest legacy of the A Chorus Line film is as a fascinating case study in the perennial challenge of stage-to-screen adaptation – a reminder that sometimes, the most powerful magic is that which can only truly exist within the shared, ephemeral space of a darkened theatre.