The world outside the flickering screen might be dark, but it’s nothing compared to the perpetual, sickly twilight drowning Lars von Trier's audacious 1984 debut, The Element of Crime (Danish: Forbrydelsens element). Forget sunshine; this is a landscape bleached by sodium lamps, drenched in endless rain, and steeped in a decay so profound it feels like the continent itself is rotting from the inside out. Watching it then, likely on a worn-out rental tape procured from the shadowy back shelves of the video store, felt less like viewing a movie and more like succumbing to a fever dream – a hypnotic state from which escape seems improbable.

A Descent into Visual Oppression

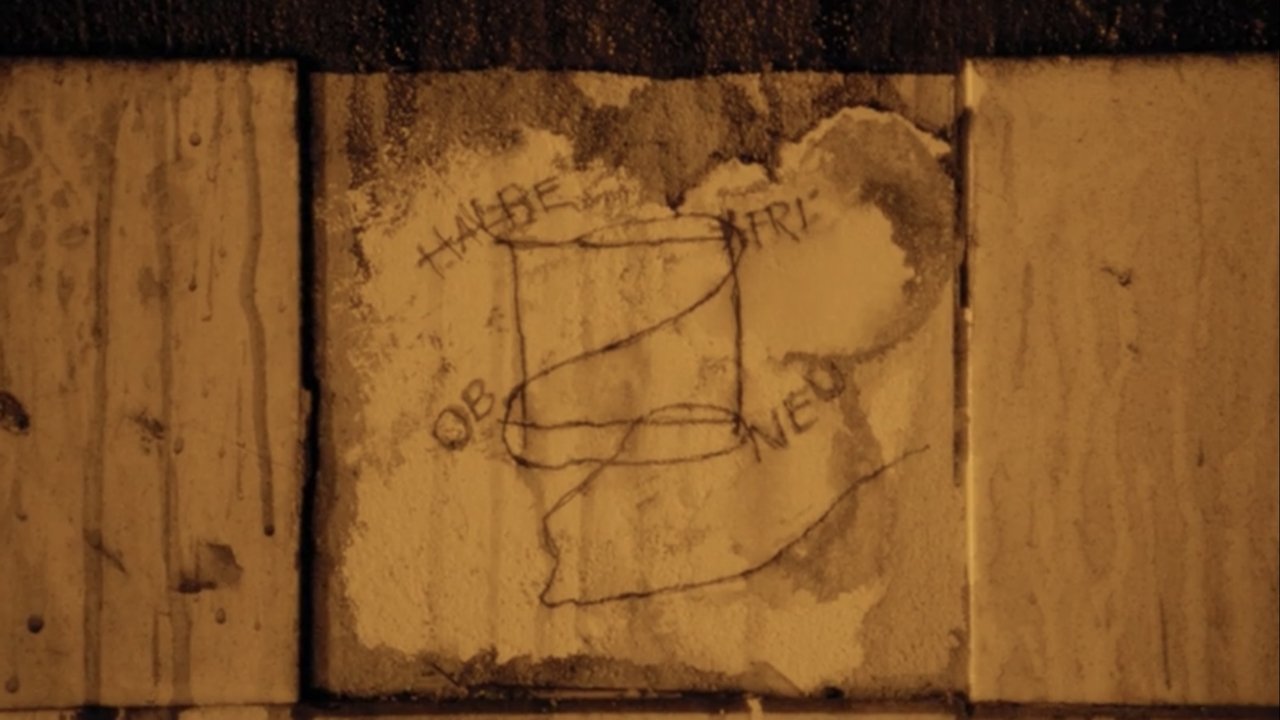

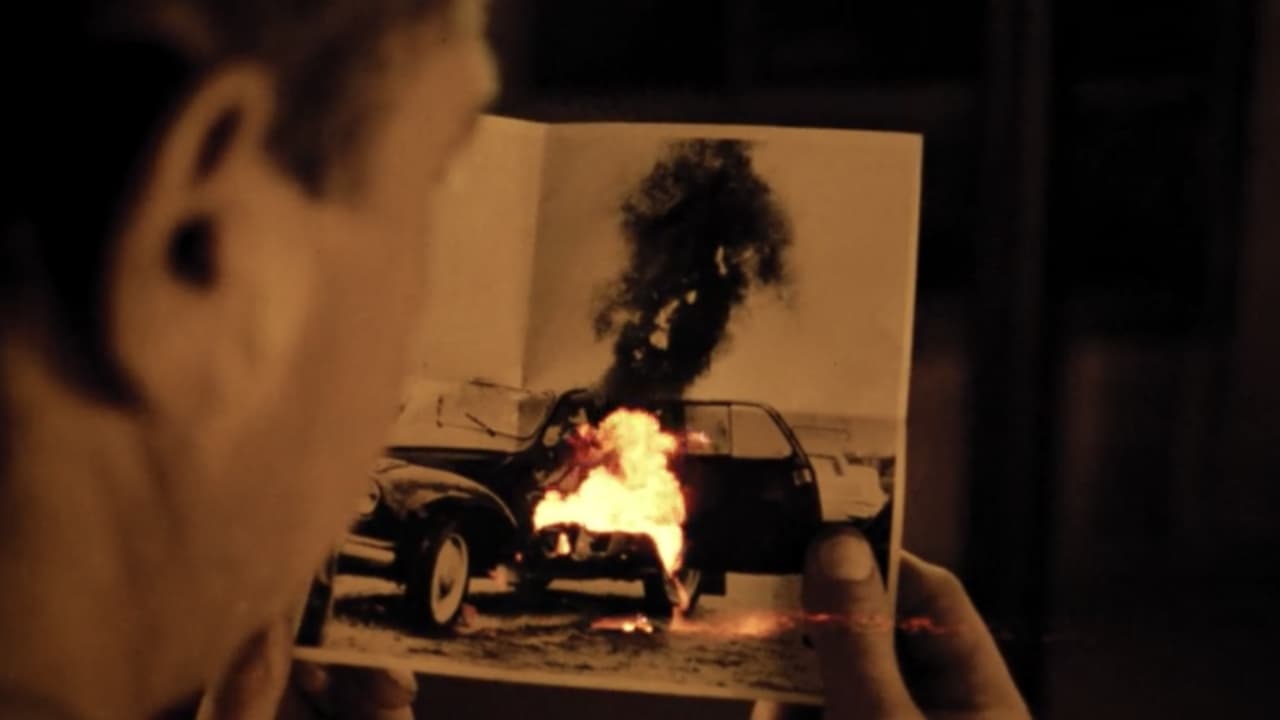

From the opening frames, von Trier plunges us into an aesthetic stranglehold. The film is relentlessly, unnervingly yellow. This wasn't just a stylistic whim; it was a technical choice born partly from necessity and partly from vision. Utilising the same kind of sodium streetlights that cast that eerie, crime-scene glow over real-world nocturnal streets, cinematographer Tom Elling crafts a Europe perpetually suspended between dusk and dawn, a visual metaphor for the moral ambiguity soaking through every frame. Remember seeing those visuals bleed and bloom on a CRT screen? That specific texture, that almost tangible grime, only intensified the feeling of being submerged in Fisher’s disintegrating psyche. The constant downpour isn't just weather; it's a viscous, cleansing agent that never quite washes away the filth.

Hypnosis as Narrative

The plot, such as it is, follows Detective Fisher (Michael Elphick), exiled in Cairo, undergoing hypnosis to recall his last case in Europe. He was investigating a series of grisly child murders, guided by the controversial methods of his disgraced mentor, Osborne (Esmond Knight). Osborne’s book, "The Element of Crime," posits that to catch a killer, one must become the killer – empathise, retrace their steps, inhabit their mindset. It's a dangerous path, and von Trier, along with co-writer Niels Vørsel, uses this framework not for a standard procedural, but for a spiralling descent into obsession. The narrative structure, fragmented by the hypnotic recall and Fisher’s increasingly unreliable narration, mirrors the detective's mental unravelling. The dialogue often feels repetitive, almost ritualistic, pulling the viewer deeper into the film’s strange trance.

Faces in the Gloom

Michael Elphick, familiar to many British viewers from the long-running series Boon, brings a weary, haunted quality to Fisher. He’s less a hardboiled detective and more a ghost drifting through a ruined world, his empathy curdling into something far darker. Opposite him, Esmond Knight lends a fragile authority to Osborne. Knight, an actor whose career remarkably continued after being blinded during naval service in World War II, delivers his lines with a chilling conviction that makes the Osborne Method feel disturbingly plausible within the film’s warped reality. Even the presence of Me Me Lai, known for starkly different roles in infamous Italian cannibal films, adds to the disorienting, almost transgressive texture of the cast. The performances are stylized, fitting the artificiality of the world von Trier creates.

Forging a Dark Vision

As Lars von Trier's feature film debut, The Element of Crime was a statement of intent. The first part of his thematic "Europa Trilogy" (followed by 1987's Epidemic and 1991's Europa / Zentropa), it showcased a filmmaker already fascinated with formal experimentation, provocation, and plumbing the depths of human darkness. Shot primarily in English to chase international audiences – a bold move for a Danish production with a relatively modest budget (reportedly around $1 million) – it immediately polarised critics. While its suffocating style wasn't universally loved, its technical mastery, particularly the cinematography, couldn't be ignored, earning it the Technical Grand Prize at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival. Influences from Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982) in its depiction of urban decay and the existential dread of Andrei Tarkovsky's work are palpable, yet von Trier synthesises them into something uniquely his own – a bleak, European counterpoint to slicker Hollywood fare.

Lingering Unease

Finding The Element of Crime on VHS back in the day felt like uncovering a forbidden text. It wasn't the kind of movie you easily recommended or discussed casually. It was dense, demanding, and deliberately off-putting, yet utterly mesmerizing in its commitment to its bleak vision. Does that pervasive yellow light still feel oppressive? Does the film’s deliberate pacing still test patience while simultaneously tightening the screws of dread? Absolutely. It’s not an easy watch, nor was it ever intended to be. It’s a challenging piece of 80s art house cinema that uses the framework of a thriller to explore far more disturbing philosophical territory.

***

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable artistic power, its groundbreaking visual style, and its sheer audacity as a debut feature. Von Trier crafted an unforgettable atmosphere of dread and decay, pushing cinematic language in bold directions. It loses points perhaps for its sometimes alienating coldness and deliberate pacing, which certainly won't appeal to everyone, but its technical brilliance and thematic depth are undeniable.

Final Thought: The Element of Crime remains a potent dose of European existential dread, a stark reminder from the VHS era that sometimes the most unsettling horrors aren't monsters, but the murky landscapes of the human mind reflected in a dying world. It’s a film that stains your memory long after the tape stops rolling.