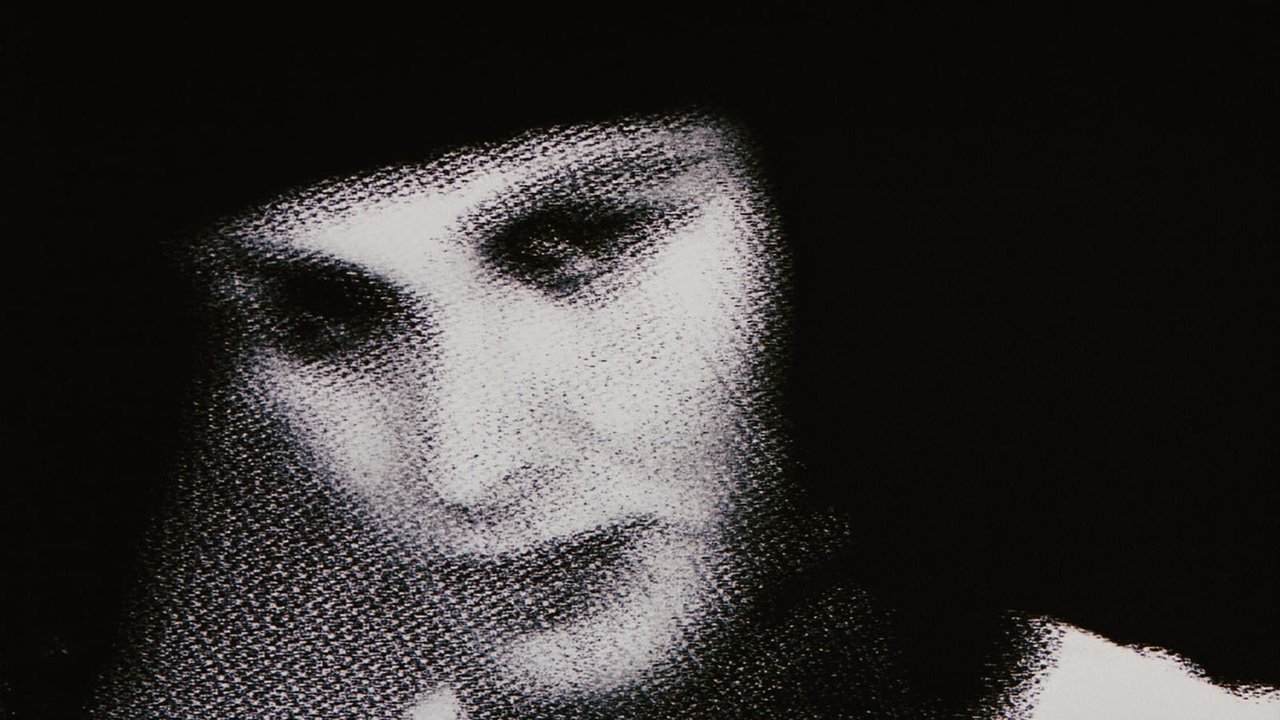

Here we are, fellow travellers in time, digging through the magnetic tape stacks of memory. Sometimes you pull out a familiar favourite, worn smooth by countless viewings. Other times, you unearth something vast, ambitious, maybe even a little unwieldy – a film that tried to grasp the future and, in doing so, perfectly captured a specific moment in the past. Wim Wenders' Until the End of the World (1991) is undeniably one of the latter. Forget a simple story; this film is a sprawling, globe-trotting odyssey that feels less like a movie you watch and more like a strange, prophetic dream you drift through.

A Planet on the Brink, A Woman on the Run

The year is 1999 – a near-future imagined from the cusp of the 90s. An Indian nuclear satellite is out of control, threatening global catastrophe and casting a strange, anxious pall over everything. Amidst this simmering apocalypse, we follow Claire Tourneur (Solveig Dommartin), a restless soul drifting through life until a chance encounter (and car crash) throws her into the path of the enigmatic Sam Farber (William Hurt). Sam is pursued by shadowy figures, carrying a revolutionary piece of technology: a camera, developed by his scientist father (Max von Sydow), capable of recording visual experiences directly from the brain, intended initially to allow his blind mother (Jeanne Moreau) to see. Claire, inexplicably drawn to Sam, joins the chase, pursued herself by her novelist ex-boyfriend Eugene (Sam Neill), who chronicles their chaotic journey. What unfolds is less a conventional thriller and more a hypnotic pursuit across continents – Lisbon, Paris, Berlin, Moscow, Tokyo, San Francisco, eventually leading to the Australian outback.

Seeing the Future Through Yesterday's Eyes

One of the most fascinating aspects of revisiting Until the End of the World now is its vision of technology. Wenders, ever the cinematic philosopher preoccupied with images, loaded the film with tech that felt cutting-edge then and feels remarkably prescient now. Characters navigate using satellite mapping systems on handheld devices, make video calls across the globe, and interact with sophisticated computer interfaces. It's genuinely startling to see these concepts, now utterly mundane, depicted with such earnest futurism. There's a distinct thrill in knowing that Wenders actually pushed technological boundaries during production, collaborating with companies like Sony to experiment with and feature early High-Definition video systems within the film itself, years before HD became standard. Watching these crisp, digital images within the movie, rendered through the warm, occasionally wobbly analogue glow of VHS... well, it’s a unique kind of temporal whiplash, isn't it?

The Intoxicating Danger of Recorded Dreams

Beyond the gadgets, the film delves into profound questions about perception, memory, and the very nature of seeing. The stolen camera isn't just a MacGuffin; it becomes the catalyst for exploring what Wenders, who gave us the searching angels of Wings of Desire (1987), clearly saw as a looming human condition: the addiction to images. Once the characters reach the hidden lab in the Australian outback and refine the technology to not just record, but replay their own dreams and memories, the film takes a darker, more introspective turn. The initial wonder gives way to obsession, a narcissistic loop where mediated experience trumps reality. It's a powerful, cautionary exploration of technology's potential to isolate even as it connects, a theme that resonates perhaps even more strongly today than it did in 1991. Doesn't this descent into self-absorbed digital cocoons feel hauntingly familiar?

Performances Painted on a Global Canvas

Anchoring this sprawling narrative requires compelling performances, and the cast delivers. Solveig Dommartin (Wenders' creative and life partner at the time, who tragically passed away far too young in 2007) is the film's restless heart. She embodies Claire's impulsive energy and eventual vulnerability with a captivating presence. It's worth noting Dommartin threw herself into the role, even learning trapeze artistry for a sequence showcasing Claire's search for meaning. William Hurt, fresh off acclaimed roles like Broadcast News (1987), brings his signature enigmatic intensity to Sam Farber, a man literally haunted by visions. And Sam Neill, providing the narrative voiceover, offers a grounding counterpoint as Eugene, the observer trying to make sense of the whirlwind. The legendary Max von Sydow and Jeanne Moreau lend immense gravitas to their crucial supporting roles.

Retro Fun Facts: An Epic Undertaking

The making of Until the End of the World was almost as epic as the film itself. Conceived by Wenders back in the late 70s, it finally went into production with a hefty budget (reportedly around $23 million – a staggering sum for a European art film then, roughly $50 million today) funded internationally. The logistics were mind-boggling: shooting took place across roughly 15 cities in 7 different countries, spanning nearly a year. This wasn't just location hopping; it was embedding the story in a truly global context.

Perhaps the most crucial piece of trivia, especially for VHS hunters, concerns the film's length. The version most audiences saw in cinemas (and likely rented initially) was a compromised theatrical cut, running about 2.5 hours, which was poorly received critically and commercially. Wenders, however, always envisioned a much larger canvas. His definitive Director's Cut, clocking in at nearly five hours (287 minutes!), was later released and is widely considered the true version of the film. Finding that double-VHS set back in the day felt like unearthing a hidden cinematic monument. If you've only seen the shorter version, the longer cut is a completely different, far richer experience.

And that soundtrack! Wenders asked artists like U2, R.E.M., Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Depeche Mode, Talking Heads, Lou Reed, and Patti Smith to contribute original songs, imagining the music they might be making in the year 1999. The resulting album is an absolute time capsule of alternative rock royalty, perfectly complementing the film's mood.

Legacy on Magnetic Tape

Watching Until the End of the World on VHS, especially if you track down the full Director's Cut (perhaps across two tapes!), is a commitment. It demands patience. Its pace is deliberate, meditative, sometimes bordering on languid. It's not a film that provides easy answers or neat resolutions. Yet, its ambition is undeniable, its visual poetry often breathtaking, and its core concerns about technology and the human spirit remarkably forward-thinking. It might not have been a blockbuster, but it's a cult classic sci-fi VHS gem that has lingered in the minds of those who embarked on its unique journey. It’s a film that truly feels like it came from another time, dreaming of a future we now inhabit, warts and all.

Rating: 8/10 (Based on the Director's Cut – the theatrical cut would rate lower). The score reflects the film's profound ambition, its prescient themes, stunning global cinematography, unforgettable soundtrack, and committed performances. It loses points for occasional pacing issues inherent in its epic length and a narrative that sometimes feels as wandering as its protagonist, but the overall achievement, especially in its intended form, is remarkable.

It leaves you contemplating the images that shape our lives – both the ones we see on screens and the ones we replay in our minds. What visions, you wonder, are we chasing towards the end of our world?