It begins not with fevered desperation in Tsarist Russia, but with the cold, methodical routine of a Helsinki slaughterhouse worker. This stark opening image immediately signals that Aki Kaurismäki's 1983 debut feature, Rikos ja Rangaistus (or Crime and Punishment as we knew it on those precious, often slightly worn rental tapes), isn't interested in merely transposing Dostoevsky's towering novel. Instead, it uses the familiar framework to explore something uniquely Finnish, chillingly modern, and profoundly unsettling. Forget the grand philosophical debates screamed across dimly lit rooms; this is nihilism served cold, under the flat, unforgiving light of the Nordic everyday.

I remember finding this one tucked away in the 'World Cinema' section of my local video haunt, a stark contrast to the explosive covers nearby. It felt like a dare, a promise of something demanding. And it delivered. Watching it again now, the film’s deliberate pace and minimalist aesthetic feel less like a product of budgetary constraint (though that was surely a factor for a debut) and more like a conscious artistic choice that perfectly mirrors the protagonist's profound alienation.

A Helsinki Raskolnikov

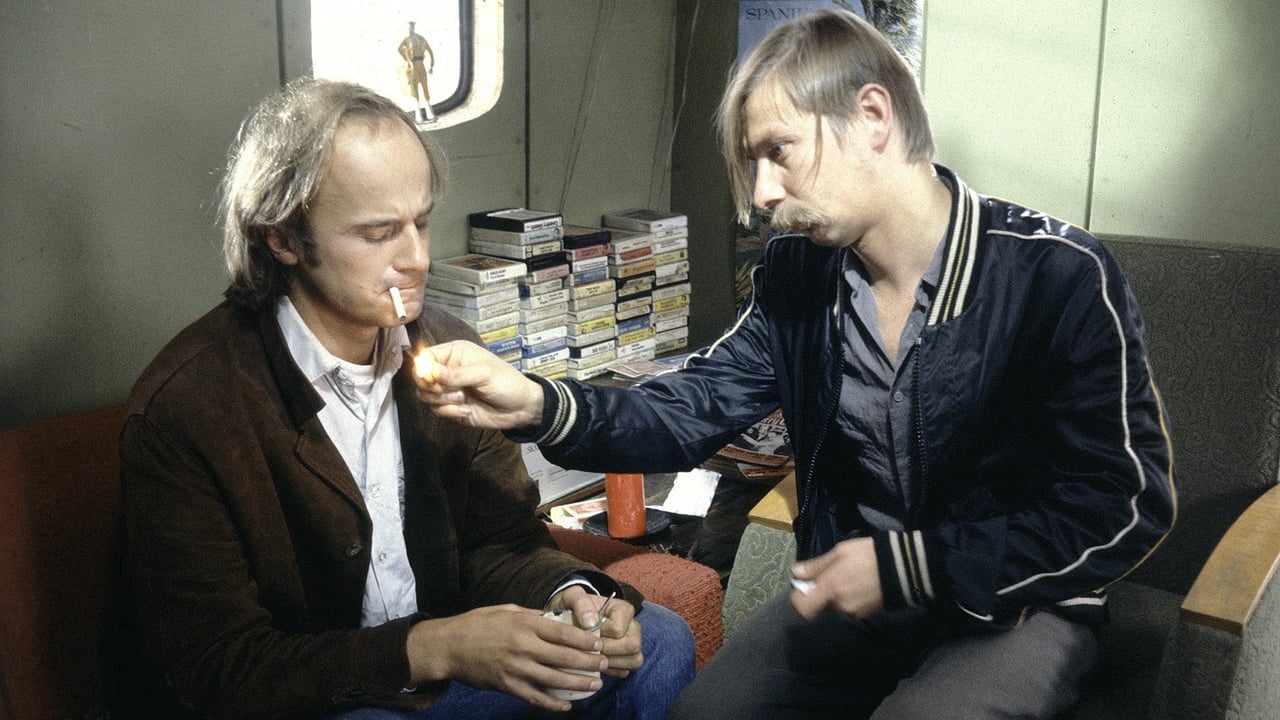

At the heart of the film is Antti Rahikainen, played with unnerving stillness by Markku Toikka. He’s our Raskolnikov, reimagined not as an impoverished intellectual, but as a former law student now working a grim, blue-collar job. The murder he commits – targeting a wealthy businessman responsible for the death of his fiancée years earlier – lacks the frantic energy of the novel. It’s calculated, almost detached, performed with a chilling precision that makes it all the more disturbing. Toikka’s genius lies in his restraint; his face is often a mask, but beneath the surface, you sense a universe of suppressed rage, guilt, and existential dread churning. There are no histrionics, just the heavy weight of his actions pressing down on him, visible in the slump of his shoulders or the vacancy in his eyes. It's a performance that burrows under your skin precisely because it refuses easy emotional access.

Kaurismäki's Emerging Vision

Even in this first film, the hallmarks of Kaurismäki's distinctive style are remarkably present. The sparse dialogue, where silence often speaks volumes more than words. The static camera compositions that frame characters against bleak urban landscapes – anonymous concrete buildings, sterile interiors, dimly lit bars populated by solitary figures. The deadpan delivery, occasionally hinting at a dark, almost imperceptible humor born from absurdity. It's a Helsinki stripped of postcard charm, rendered as a character in itself – indifferent, perhaps even hostile, to the human dramas unfolding within it. You can see the DNA here that would blossom in later, more internationally recognised works like The Match Factory Girl (1990) or Le Havre (2011). This wasn't just an adaptation; it was the announcement of a singular cinematic voice.

Interestingly, Kaurismäki reportedly secured the rights by simply phoning the Dostoevsky estate and asking – a wonderfully direct approach that feels somehow in character with his filmmaking. The production itself was lean, embodying the 'less is more' philosophy. This wasn't the polished sheen of Hollywood; it felt raw, grounded, almost documentary-like at times, which only enhances the feeling of unease.

Themes That Endure

While the setting is updated, the core questions remain potent. What happens when societal structures fail an individual? Where does justice lie when the legal system seems inadequate or corrupt? Rahikainen’s crime isn't driven by poverty or a misguided philosophical theory, but by a cold, simmering desire for revenge, a personal reckoning against a man he sees as embodying systemic injustice. The film forces us to confront uncomfortable ideas about morality, guilt, and the possibility (or impossibility) of redemption in a world that often feels devoid of meaning. The relationship between Rahikainen and Eeva (Aino Seppo, embodying the film's Sonia figure), a witness who becomes entangled in his fate, offers a glimmer of human connection, but even this is fraught with ambiguity and tension. Can empathy truly penetrate such profound isolation?

Retro Reflections

Watching Crime and Punishment (1983) today is a fascinating experience. It lacks the kinetic energy or overt stylization we often associate with 80s cinema. It demands patience and rewards contemplation. It’s a film that might have bewildered someone expecting a straightforward thriller back in the rental days, but for those willing to meet it on its own terms, it offers a powerful and lingering experience. It’s a reminder that even within the familiar confines of VHS tapes and CRT screens, there were challenging, auteur-driven works waiting to be discovered, offering starkly different visions of the world. This wasn't feel-good entertainment; it was cinema as a cold shard of glass, reflecting uncomfortable truths.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's artistic integrity, its haunting atmosphere, and Markku Toikka's remarkable central performance. It's a powerful, if bleak, debut that successfully translates Dostoevsky's themes into a modern, minimalist context. It loses a couple of points perhaps for its demanding nature and deliberate pacing, which might not resonate with all viewers, especially those seeking conventional thrills. Yet, its unique vision and Kaurismäki's confident direction make it a standout piece of 80s arthouse cinema.

It's a film that doesn't fade quickly after the credits roll. Instead, it leaves you pondering the silence, the stares, and the cold weight of consequence in a modern world. A truly arresting start for one of Finland's most distinctive cinematic voices.