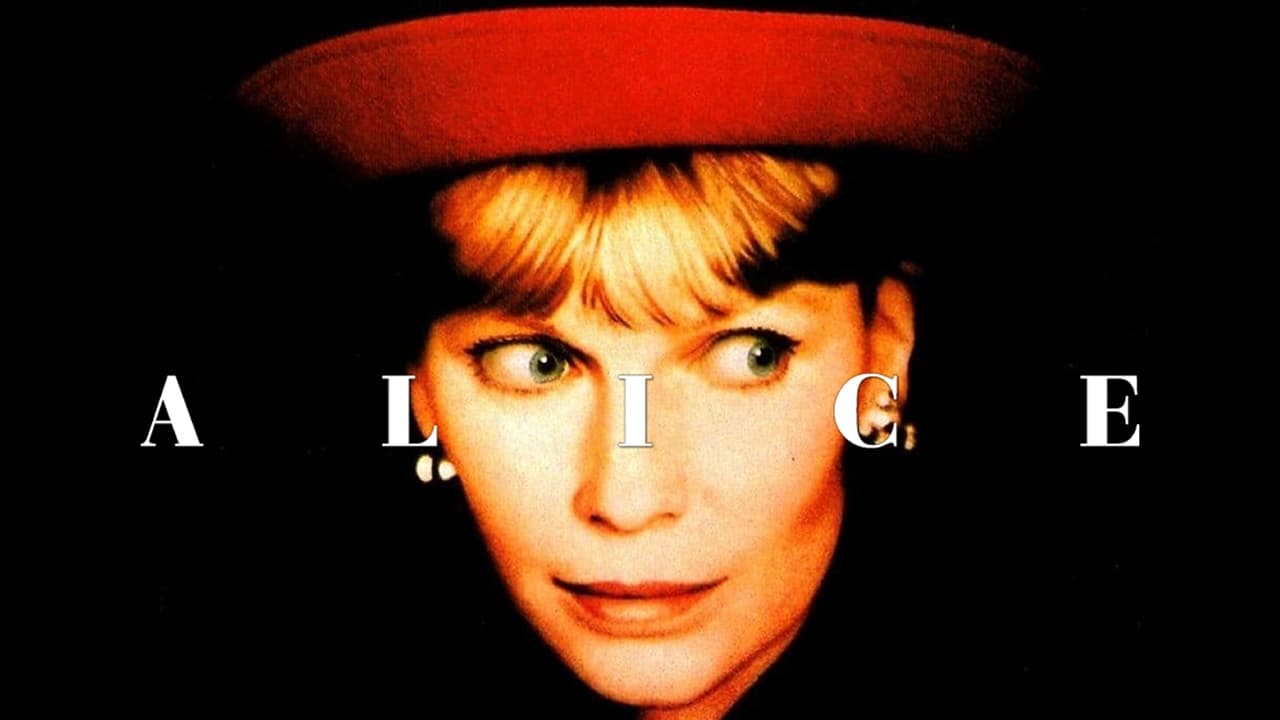

There's a particular kind of quiet desperation that sometimes settles over lives lived in gilded cages, a theme Woody Allen explored with a unique, fantastical twist in his 1990 film, Alice. It wasn't the typical Allen neurotic comedy or stark relationship drama that often graced the shelves of my local video rental spot back then. Seeing Mia Farrow's face on the VHS cover promised something familiar, yet the synopsis hinted at... magic? In Manhattan? It felt like an intriguing departure, a story whispering that sometimes the most extraordinary journeys begin with the most ordinary aches.

Beneath the Upper East Side Gloss

We meet Alice Tate (Mia Farrow) living a life many would envy: married to the wealthy, perpetually busy Doug (William Hurt), raising two children, filling her days with shopping, spa treatments, and charity functions. Yet, beneath the perfectly applied makeup and expensive clothes, there's an undeniable emptiness, a vague dissatisfaction she can't quite articulate. It's a portrayal Farrow navigates with remarkable subtlety. Her Alice isn't overtly unhappy at first, more... adrift. She embodies that specific paralysis of privilege, where having everything somehow leaves you feeling you have nothing of real substance. Her back aches, a psychosomatic manifestation, perhaps, of a deeper malaise.

It’s this ache that leads her, hesitantly, into the dimly lit, mysterious Chinatown office of Dr. Yang (Keye Luke, in his final film role, bringing a wonderful gravitas). This encounter is the catalyst that shifts the film from a recognizable Manhattan story into something else entirely. Dr. Yang, part herbalist, part therapist, part magician, offers Alice remedies that do far more than soothe back pain. They grant invisibility, allow her to fly, conjure the ghost of a past lover (a charmingly spectral Alec Baldwin), and reveal uncomfortable truths about those around her.

Whispers of Magic, Echoes of Truth

The magic here isn't flashy; it feels strangely organic, woven into the fabric of Alice's increasingly surreal experiences. Allen, who also penned the Oscar-nominated screenplay, uses these fantastical elements not just for whimsical effect, but as tools for introspection. What happens when the masks we wear, and the masks others present to us, are suddenly stripped away? Becoming invisible allows Alice to eavesdrop, confirming her suspicions about Doug's infidelity and uncovering the shallow judgments of her supposed friends. It’s a cleverly executed device, forcing Alice (and us) to confront the often-unpleasant reality hiding beneath social niceties.

Interestingly, the film's production wasn't without its own touch of the unexpected. Apparently, the budget for Alice hovered around $12 million, but it only managed to conjure about $5.3 million at the US box office. Perhaps audiences in 1990 weren't quite ready for this specific blend of Allen's urban angst and overt fantasy, expecting something more along the lines of Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) or Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989). Critics, too, were somewhat divided, though many acknowledged the clear nods to Federico Fellini's Juliet of the Spirits (1965), another film exploring a bourgeois wife's fantastical journey of self-discovery. It feels less like direct imitation and more like a respectful homage, filtered through Allen's distinct New York sensibility.

Farrow's Quiet Awakening

At the heart of it all is Mia Farrow. This was her tenth cinematic collaboration with Allen, and her performance is the film's anchor. She beautifully charts Alice's transformation from a passive, almost childlike figure, defined entirely by her roles as wife and mother, into someone actively seeking her own identity and purpose. There's a quiet strength that emerges as she experiments with the herbs, confronts uncomfortable truths, and tentatively pursues a connection with the sensitive, jazz-loving Joe (Joe Mantegna, radiating warmth and sincerity). The supporting cast, including Judy Davis and Bernadette Peters, populates Alice's world with vivid, if sometimes fleeting, characters, adding layers to the social milieu she ultimately questions. William Hurt effectively embodies the detached, slightly condescending husband, making Alice’s desire for something more entirely understandable.

The film doesn't shy away from Alice's Catholic upbringing, weaving in conversations with ghostly nuns and lingering guilt, adding another dimension to her search for meaning beyond materialism. Is genuine fulfillment found in spirituality, romance, altruism, or simply in becoming authentically oneself? Alice doesn't offer easy answers, preferring instead to follow its protagonist through her messy, magical, and ultimately liberating exploration. Cinematographer Carlo Di Palma, a frequent Allen collaborator, captures both the sterile perfection of Alice's initial world and the slightly hazy, dreamlike quality of her transformative experiences with equal skill.

A Different Kind of Spell

Alice might not be the first Woody Allen film that springs to mind, sandwiched between some of his more lauded works. It lacks the sharp comedic bite of his earlier films and the searing dramatic intensity of others. Yet, revisiting it now, perhaps with the distance afforded by time and the soft glow of VHS nostalgia, reveals a gentle, thoughtful film with a unique charm. It’s a modern fairytale set amongst the brownstones and boutiques of Manhattan, asking profound questions about happiness, identity, and the courage it takes to truly see oneself and the world around us, even if it requires a little bit of magic to open our eyes. What invisible walls do we erect in our own lives, and what might happen if we dared to dissolve them?

---

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: Alice is a beautifully acted and visually distinct film, anchored by a superb central performance from Mia Farrow. Its blend of magical realism and relationship drama is unique within Woody Allen's filmography, offering thoughtful commentary on self-discovery and societal pressures. While the pacing sometimes meanders slightly and the fantasy elements might not resonate with everyone, its quiet charm, atmospheric direction, and Farrow's compelling journey make it a worthwhile and often overlooked gem from the era. The integration of fantasy feels purposeful, serving the thematic core rather than just being spectacle.

Final Thought: It lingers not as Allen's funniest or most profound film, but perhaps as one of his most hopeful – a quiet suggestion that transformation is possible, even if it takes a little otherworldly assistance to begin.