There's a peculiar chill that settles over The Osterman Weekend, a feeling that lingers long after the distinct whir of the VCR powering down. Released in 1983, it arrived steeped in the miasma of late Cold War paranoia, but its central dread feels unnervingly contemporary. It wasn't just about spies and shadowy government agencies then; it was about the insidious nature of observation, the weaponization of screens, and the terrifying ease with which trust could be shattered. Watching it again now, on a format far removed from the multiplex, that chill feels less like a product of its time and more like a prescient whisper of the surveillance age to come.

### A Gathering Storm

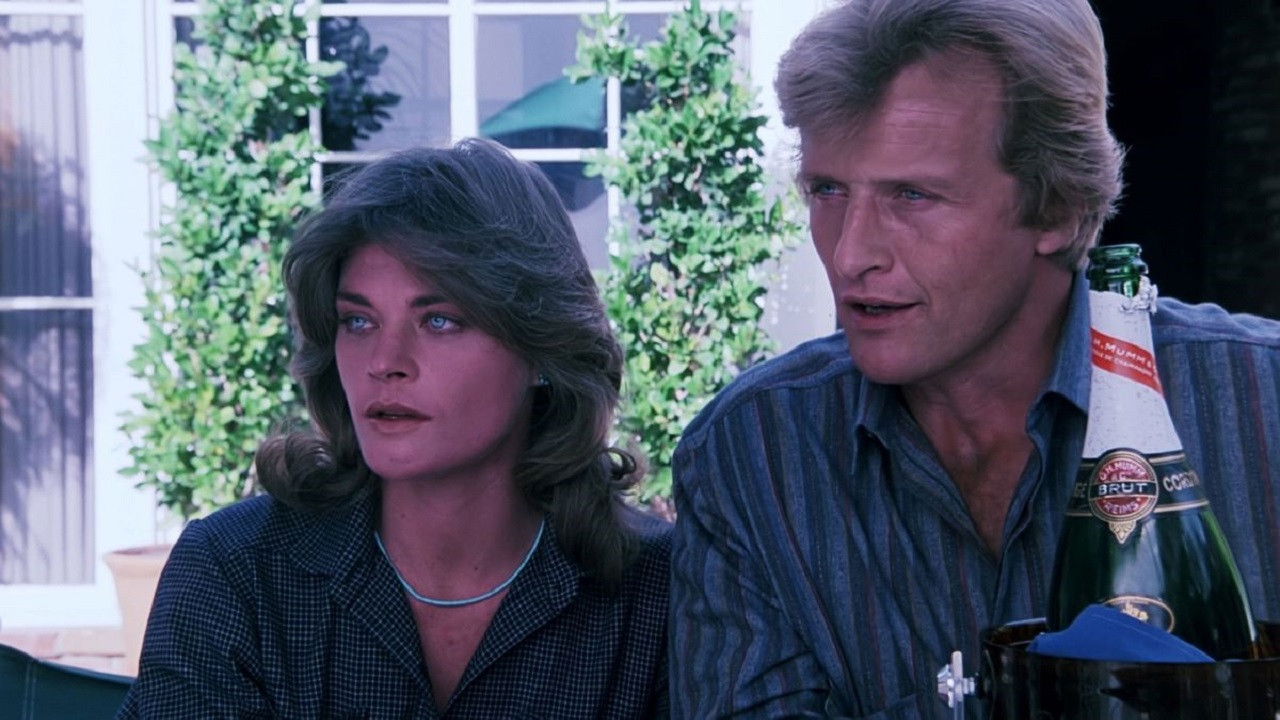

The premise, drawn from Robert Ludlum's novel (though famously altered much to his chagrin), is deceptively simple. John Tanner (Rutger Hauer, fresh off his iconic Blade Runner role), a controversial television journalist known for his confrontational style, hosts his annual reunion weekend for college buddies. It’s meant to be a relaxed affair with wives and partners at his secluded home. But before the first beer is cracked open, Tanner is cornered by cryptic CIA agent Lawrence Fassett (John Hurt, bringing an unsettling intensity honed in films like Alien and The Elephant Man). Fassett presents 'irrefutable' video evidence suggesting Tanner's close friends – amiable TV producer Bernard Osterman (Craig T. Nelson, just after Poltergeist and before his beloved Coach persona), stockbroker Joseph Cardone (Chris Sarandon), and physician Richard Tremayne (Dennis Hopper) – are actually Soviet agents involved in a treacherous network codenamed "Omega." Fassett convinces Tanner to allow the entire weekend, the house itself, to be wired for sound and video, turning the reunion into a tightly monitored trap.

### Peckinpah's Shadow

This setup drips with potential for suspense, and directing duties fell to the legendary, often volatile Sam Peckinpah. The Osterman Weekend marked a comeback attempt for "Bloody Sam" after years battling personal demons and studio interference that plagued masterpieces like Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. One can't help but wonder how much of Peckinpah's own feelings of being watched, manipulated, and betrayed by systems of power seeped into the film's DNA. While the signature slow-motion ballets of violence are less pronounced here than in The Wild Bunch, his fingerprints are still visible: the focus on masculinity under pressure, the simmering resentment between characters, and a deep-seated cynicism about institutions.

However, the film’s journey to the screen was, perhaps predictably for Peckinpah, fraught. Rumors swirled about his declining health and clashes with producers, culminating in the final cut reportedly being taken out of his hands. This turbulent production history might explain some of the film's occasional narrative unevenness or tonal shifts. It feels like a Peckinpah film filtered, perhaps diluted, through studio anxieties – a fascinating artifact in itself. Interestingly, Ludlum publicly distanced himself from the adaptation, feeling it strayed too far from his intricate plotting, focusing more on the visual surveillance aspect Peckinpah clearly found compelling.

### The Unblinking Eye

What truly elevates The Osterman Weekend beyond a standard spy thriller is its relentless focus on surveillance. The house isn't just bugged; it becomes a multi-screen television studio for Fassett and his team, hidden away in a mobile command center. We, along with Fassett, become voyeurs, scrutinizing intimate moments, searching for tells, interpreting ambiguous actions through the cold lens of suspicion. Peckinpah masterfully uses split screens and banks of monitors not just as a stylistic flourish, but to emphasize the fragmented, manipulated nature of the 'truth' being presented. The technology, cutting-edge for 1983 video equipment, feels almost quaint now, yet the idea behind it – the constant, invasive eye – has only become more potent. Doesn't this constant mediated reality, where every interaction can be recorded and replayed out of context, feel chillingly familiar?

### A Cast Caught in the Crosshairs

The ensemble cast navigates this web of deceit with skill. Rutger Hauer anchors the film as Tanner, a man whose aggressive public persona masks a growing vulnerability as his world collapses. He convincingly portrays the dawning horror of realizing he might be a pawn in a much larger, deadlier game. John Hurt is exceptional as Fassett, radiating a quiet, obsessive energy. His motivations are complex, rooted in personal tragedy, making him more than just a government stooge; he's a ghost in the machine, pulling strings with chilling precision. Craig T. Nelson, Dennis Hopper, and Chris Sarandon effectively embody the ambiguity required – are they loyal friends caught in a setup, or calculating traitors? Even screen legend Burt Lancaster, in a relatively small role as CIA Director Maxwell Danforth, lends gravitas, representing the detached, institutional power manipulating events from afar. Getting this lineup together, including Meg Foster and Helen Shaver as the increasingly suspicious wives, was a real casting coup for a film with a relatively modest budget (around $6.5 million).

### Legacy in the Static

Despite its troubled production and Ludlum's disapproval, The Osterman Weekend found a degree of success, earning back its budget and securing a long life on VHS shelves – I certainly remember spotting that distinctive cover art frequently at my local rental spot. It might not be considered top-tier Peckinpah by purists, lacking the raw, poetic nihilism of his greatest works. Yet, it remains a compelling, intelligent thriller that tackles themes ahead of its time. Its exploration of media manipulation and the psychological toll of surveillance feels remarkably relevant today, perhaps even more so than it did in 1983. The paranoia it taps into is no longer confined to Cold War espionage; it’s woven into the fabric of our digital lives.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: While studio interference arguably sands down some of Peckinpah’s rougher edges and leaves a few narrative threads feeling slightly underdeveloped, The Osterman Weekend is anchored by its powerful central theme, a pervasive atmosphere of dread, and truly stellar performances, particularly from Hauer and Hurt. Its prescient focus on surveillance and the tension it builds makes it a significant, if slightly flawed, entry in the 80s thriller canon.

Final Thought: It’s a film that leaves you checking over your shoulder, not for spies, but for the myriad screens that now quietly observe our own Osterman weekends. What truths, you wonder, are being edited for us?