It often starts with a jarring contrast, doesn't it? The sterile confines of a city under siege suddenly giving way to the immense, indifferent wilderness. That's the shift that defines Shoot to Kill (1988), a film that arrived on VHS shelves feeling both familiar in its thriller mechanics and refreshingly rugged in its execution. It wasn't just another cops-and-robbers chase; it was a reminder of how unforgiving nature could be, long before CGI could paint landscapes onto a green screen.

From Concrete Jungle to Frozen Peaks

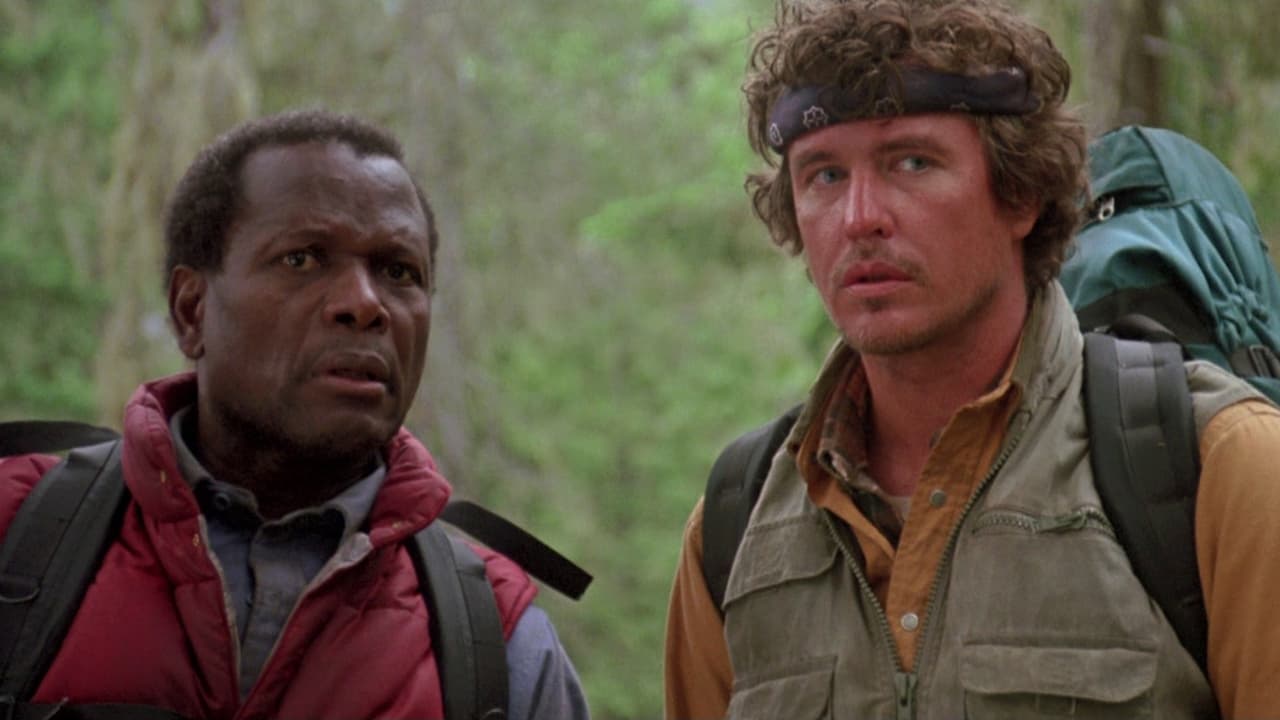

The setup is pure 80s thriller: a cunning jewel thief executes a ruthless escape in San Francisco, taking a hostage and vanishing. Enter FBI Agent Warren Stantin, played by the legendary Sidney Poitier. He's sharp, determined, but decidedly urban. When the trail leads deep into the snow-covered Cascade Mountains of the Pacific Northwest, Stantin finds himself dangerously out of his depth. His pursuit hinges on securing the help of Jonathan Knox (Tom Berenger), a reclusive mountain guide who knows the treacherous terrain like the back of his hand – and happens to be the boyfriend of the hostage, Sarah (Kirstie Alley). What unfolds is a tense, often brutal game of cat-and-mouse where the environment itself is as formidable an adversary as the killer they hunt.

The Return of a Titan

Let's be honest, a huge part of the film's initial draw, and its lasting appeal, was the return of Sidney Poitier to the silver screen. After a decade dedicated primarily to directing, his comeback to acting here felt like an event. And he doesn't disappoint. His Stantin isn't a flashy action hero; he's methodical, intelligent, possessing a quiet intensity that feels utterly authentic. You see the weight of responsibility on his shoulders, the frustration of being stripped of his usual resources, the gradual, grudging respect he develops for Knox. Poitier reportedly took some persuading to step back in front of the camera after so long, but his presence anchors the film with a gravitas that elevates the material. It paid off too – the film found its audience, becoming a solid performer at the box office, proving Poitier's star power hadn't dimmed one bit. Its $29.3 million domestic gross against a roughly $15 million budget (that's about $76 million against $39 million today) was a respectable success story.

Grit, Granite, and Great Chemistry

Opposite Poitier, Tom Berenger, fresh off his Oscar nomination for Platoon (1986), is perfectly cast as the gruff, self-reliant Knox. The initial friction between the city agent and the mountain man provides some welcome character dynamics, expertly handled by the actors and script (co-written by Daniel Petrie Jr., who penned Beverly Hills Cop, showing his knack for mismatched partners). Their relationship evolves naturally from antagonism to a pragmatic partnership forged in shared danger. Berenger embodies the physical competence needed for the role, making the survival aspects believable. And Kirstie Alley, not yet the household name Cheers would make her later that same year, gives Sarah a resilience that avoids the simple damsel-in-distress trope. She's resourceful and brave, integral to the plot beyond just being a hostage.

Where Nature Steals the Scene

Director Roger Spottiswoode, who would later helm Bond entry Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), makes masterful use of the filming locations in British Columbia, Canada. The towering peaks, icy rivers, and dense forests aren't just pretty pictures; they are an active participant in the story, dictating the pace, raising the stakes, and creating a palpable sense of isolation and danger. I distinctly remember renting this on VHS, the sheer scale of those mountain vistas feeling immense even on my parents' chunky CRT television. The commitment to practical locations and stunt work feels wonderfully tangible now. The dizzying cable car sequence, the perilous climbs, the frantic chase across a moving ferry – these set pieces have a weight and visceral impact that holds up precisely because they feel real. You can almost feel the biting wind and the treacherous footing. Reportedly, the challenging conditions on location added an extra layer of difficulty for the cast and crew, but that struggle translates into on-screen authenticity.

More Than Just a Chase

While Shoot to Kill (released as Deadly Pursuit in the UK, a title perhaps less evocative of the wilderness element) delivers the requisite thrills and spills of an 80s actioner, it lingers because of its focus on character and atmosphere. It takes its time building tension, allowing the stunning scenery to dwarf the human drama, reminding us of the characters' vulnerability. It's a fish-out-of-water story, yes, but also a survival narrative and a tense psychological game. What does Stantin's urban expertise mean when faced with an avalanche? How does Knox's knowledge of the wild stack up against a determined killer? These questions give the pursuit depth beyond just catching the bad guy.

Final Thoughts on a Rugged Gem

Shoot to Kill remains a satisfyingly sturdy thriller. It represents a particular brand of late-80s filmmaking: practical effects, compelling star power, and a story grounded in a tangible sense of place and peril. Poitier's commanding return, the strong chemistry between the leads, and the spectacular, unforgiving wilderness setting make it a standout entry in the genre from the VHS era. It might follow some familiar beats, but it executes them with grit and style.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's strong core elements: Poitier's magnetic comeback performance, the excellent pairing with Berenger, Spottiswoode's tense direction, and the truly impressive use of its rugged locations and practical stunt work. While perhaps not redefining the genre, it's a highly effective and memorable thriller that perfectly captured that late-80s blend of action and character. It’s a film that feels both thrilling and substantial, a journey worth taking again, even if just on your couch this time. What lingers most, perhaps, is that stark reminder of humanity dwarfed, yet enduring, against the vast indifference of the wild.