Okay, fellow tapeheads, let’s rewind to a time when shoulder pads were nearing their peak and comedies often tackled big ideas with… well, let's just say varying degrees of finesse. Picture this: cruising the aisles of the local video store, maybe VideoSpectrum or Palmer Video, and stumbling upon a clamshell case featuring a familiar face – George Segal – but with a premise that makes you do a double-take. That’s the vibe of 1981’s Carbon Copy, a film that tried to wrap searing social commentary inside a comedic package, right at the dawn of a new decade.

### A Premise That Pops (and Puzzles)

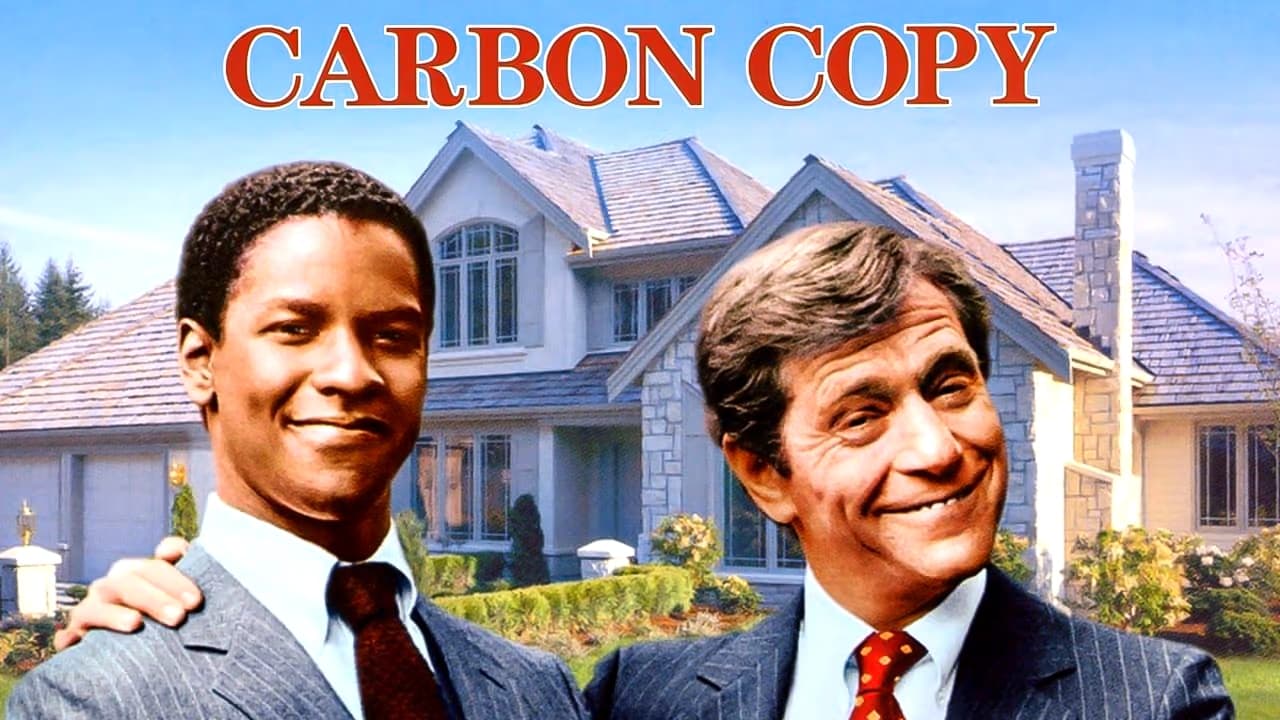

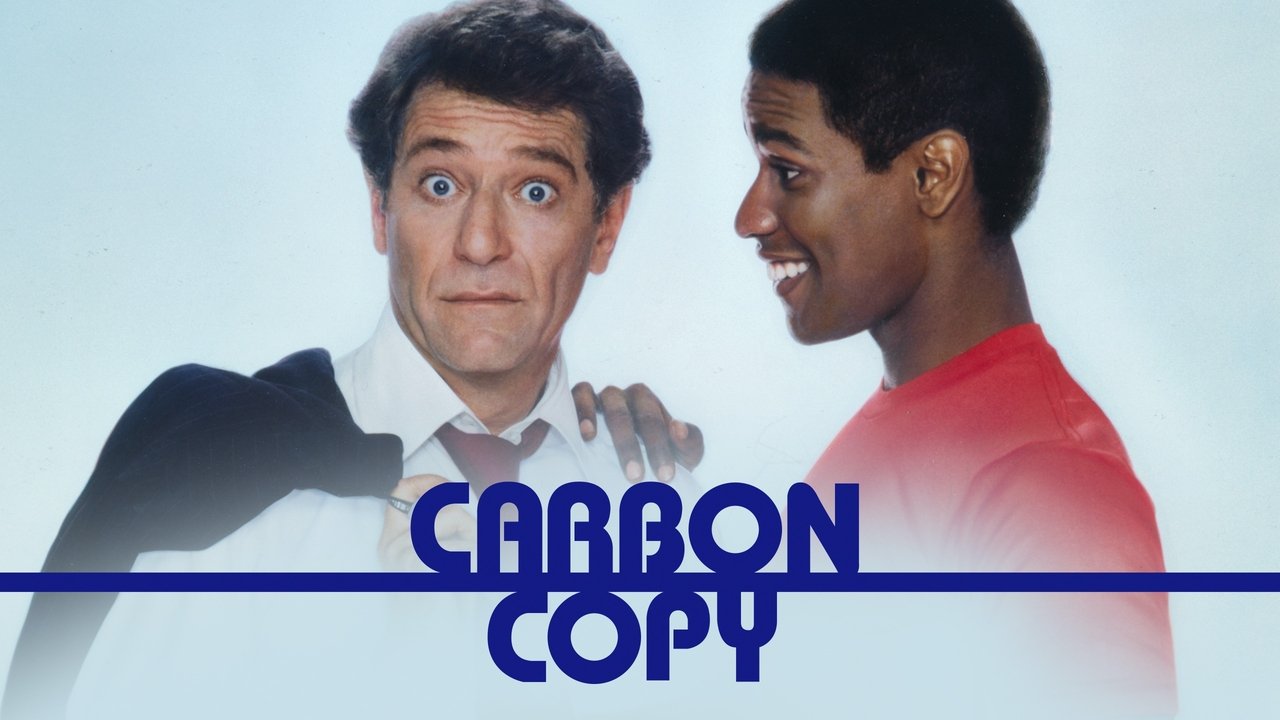

Carbon Copy kicks off in the ultra-privileged, blindingly white enclave of San Marino, California. Walter Whitney (George Segal) seemingly has it all: a high-powered executive job (thanks to his father-in-law, played with reliable bluster by Jack Warden), a perfectly manicured lawn, and a wife, Vivian (Susan Saint James, known to many from Kate & Allie), who embodies WASP-y suburban ennui. It’s a life built on comfortable denial and carefully maintained appearances. Then, the doorbell rings, and Walter's carefully constructed world detonates. Standing there is Roger Porter, a street-smart, confident young Black man claiming to be Walter’s illegitimate son from a long-ago relationship. And here’s the kicker, the "retro fun fact" that elevates Carbon Copy from mere curiosity to essential viewing for film buffs: Roger is played by a remarkably young, impossibly charismatic Denzel Washington in his feature film debut. Yes, that Denzel Washington. Seeing the future two-time Oscar winner navigate this tricky material as a newcomer is worth the price of admission (or rental fee) alone.

### Navigating Awkward Territory

Let’s be honest: watching Carbon Copy today is an exercise in navigating some seriously dated and often cringe-worthy moments. The film, penned by Stanley Shapiro (who ironically won an Oscar for the much lighter Doris Day/Rock Hudson comedy Pillow Talk (1959)), dives headfirst into racial stereotypes and the casual bigotry of the era. Walter’s panic isn't just about infidelity; it's deeply rooted in the racial implications within his prejudiced social circle. His "friends," colleagues, and even family react with cartoonish horror, stripping him of his job, home, and status almost overnight. The comedy often stems from Walter’s sheer desperation and the absurdity of his situation, but the underlying racism is played straight, making for an often uncomfortable tonal tightrope walk. Director Michael Schultz, who had helmed landmark Black-focused films like Cooley High (1975) and Car Wash (1976), brings a certain perspective, but the script's inherent awkwardness is hard to fully overcome. It feels like a film wrestling with important issues but not quite sure how to handle them without resorting to broad strokes that haven't aged particularly well.

### Segal Squirms, Washington Shines

George Segal is perfectly cast as the perpetually flustered Walter, a man whose comfortable existence crumbles into a pile of anxieties. He sells the panic and the eventual, reluctant bonding with Roger, giving the film its emotional (if shaky) anchor. His comedic timing, honed over years in films like Where's Poppa? (1970) and Fun with Dick and Jane (1977), is put to good use here, even when the situations themselves are problematic. But the real revelation is Denzel Washington. Even in his first film role, the confidence, the intelligence, the sheer star power is palpable. He imbues Roger with a dignity and self-awareness that often transcends the script's limitations. He’s not just a plot device; he’s a fully formed character navigating his own complex emotions about meeting his father and entering this hostile new world. It's fascinating to see the genesis of a legendary career in a role that required him to handle both comedic and dramatic beats, often reacting to blatant prejudice. Supporting players like Susan Saint James and Jack Warden do what’s asked of them, effectively representing the entitled, casually cruel world Walter is forced to leave behind.

### A Time Capsule Comedy

Beyond the central performances and thematic awkwardness, Carbon Copy is undeniably a product of its time. The fashion, the cars, the interior design – it all screams early 80s affluence. The film’s look isn’t particularly stylish, leaning more towards functional television aesthetics, but it effectively captures the sterile environment Walter initially inhabits. There aren’t any explosive practical effects here, obviously, but the raw, unfiltered depiction of social discomfort feels very much of that pre-digital filmmaking era – less polished, perhaps more willing to be messy. Did it find its audience back then? Not really. Carbon Copy was largely ignored, a box office disappointment that quickly faded. I distinctly remember seeing the VHS box lingering on rental shelves for years, often overlooked. It wasn't a blockbuster, nor did it become a widely celebrated cult classic. It existed in that strange purgatory of "available on tape," waiting for curious viewers.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

The Justification: Carbon Copy gets points for its audacious premise, George Segal’s committed performance, and, most importantly, as the fascinating big-screen debut of Denzel Washington. However, its clumsy handling of racial themes and reliance on dated stereotypes makes it a frequently uncomfortable watch. The tonal shifts between broad comedy and serious social commentary don't always land smoothly. It's more of a historical curiosity and a testament to Washington's early talent than a genuinely great comedy.

Final Thought: It’s a cinematic artifact dug up from the back of the VHS shelf – sometimes awkward, occasionally insightful, and absolutely essential viewing just to witness Day One of Denzel. Just be prepared to wince as often as you chuckle.