Okay, let's dim the lights, settle into that comfortable armchair, and rewind to a time when American cinema felt a little looser, a little shaggier, and infinitely more interested in the quirks of ordinary lives. Tonight's tape? Jonathan Demme's beautifully observed slice-of-life, Melvin and Howard (1980). What strikes you first, maybe years after seeing it or perhaps discovering it anew, isn't a high-concept plot, but a feeling – a dusty, sun-bleached sense of place and the hazy contours of the American Dream, viewed from the cracked vinyl seat of a pick-up truck.

It begins, as strange tales often do, in the middle of nowhere. A beat-up truck, a hopeful but perpetually down-on-his-luck Melvin Dummar (Paul Le Mat), and a motorcycle crash victim lying by the roadside in the Nevada desert. That victim? None other than the reclusive, eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes, played with a fragile, almost spectral weariness by the great Jason Robards. Their brief encounter, filled with Melvin's earnest singing (at Hughes' request) and Hughes' quiet bemusement, forms the film's strange, magnetic core. Did it really happen? Does it ultimately matter? The film, penned with remarkable empathy by Bo Goldman (who deservedly won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, adding to his statue for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975)), seems less concerned with historical fact than with the possibility – the sheer, oddball chance that such disparate lives could intersect.

Ordinary Lives, Extraordinary Moments

What follows isn't a breathless thriller about the contested will that surfaces years later, naming Melvin an heir (though that event frames the narrative). Instead, Demme, long before he terrified us with The Silence of the Lambs (1991) or moved us with Philadelphia (1993), crafts a patient, deeply human portrait of Melvin's chaotic life. Le Mat, who many might remember from American Graffiti (1973), embodies Melvin with an infectious, almost childlike optimism that constantly bumps up against harsh realities. He’s a dreamer, a schemer, a guy always chasing the next big break – a milk delivery route, a gas station – but fundamentally decent, even when making questionable choices. You root for him, even as you shake your head.

This isn't just Melvin's story, though. It’s equally, perhaps even more powerfully, the story of his first wife, Lynda. And folks, let's talk about Mary Steenburgen. Winning the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for this role wasn't just deserved; it felt inevitable once you saw her performance. She is Lynda – hopeful, frustrated, funny, and heartbreakingly real. Her journey from starry-eyed newlywed to disillusioned go-go dancer trying to make ends meet is portrayed with zero condescension. Remember that scene on the game show "Easy Street"? Or her audition tap-dancing (reportedly based on Steenburgen's own talent show past) which manages to be both hilarious and poignant? It’s acting of the highest caliber, grounded in recognizable emotion. She steals every scene she’s in, not through grandstanding, but through sheer authenticity.

The Feel of the Era

Watching Melvin and Howard now feels like unearthing a time capsule, not just of the late 70s/early 80s setting, but of a certain kind of American filmmaking. Demme's direction is refreshingly unhurried. He lets scenes breathe, capturing the textures of roadside diners, cheap apartments, and the vast, indifferent landscapes of Nevada and Utah (where much of the film was shot). There's a lived-in quality here, amplified by Demme's penchant for casting locals and using real locations, that feels miles away from glossy Hollywood productions. It’s the kind of film you might have stumbled upon in the video store, perhaps drawn in by the familiar names or the intriguing premise, and found yourself unexpectedly captivated by its low-key charm.

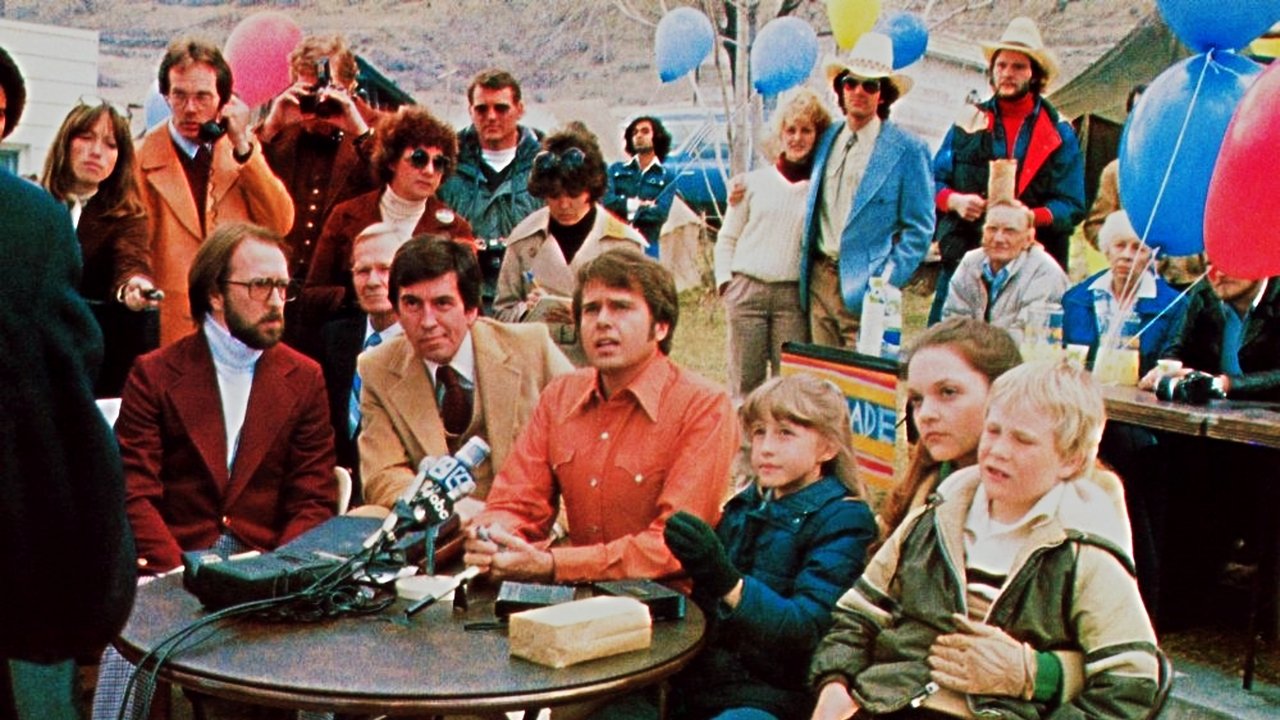

It’s fascinating to learn that the real Melvin Dummar actually has a blink-and-you'll-miss-it cameo in the film, working behind the counter in the bus station scene where Lynda leaves him. It adds another layer to the film’s blurring of fact and fiction. Despite the critical acclaim (Pauline Kael famously championed it, and Roger Ebert gave it four stars), Melvin and Howard wasn't a box office hit, pulling in only around $4.3 million on a $7 million budget. Perhaps its gentle pace and focus on flawed, ordinary people wasn't what audiences were craving as the blockbuster 80s dawned. But its lack of commercial success only enhances its standing now as a cult favorite, a hidden gem for those who appreciate character over spectacle.

Finding the Truth in the Telling

Does the film definitively answer whether Hughes left Melvin $156 million? No, and that’s precisely the point. Goldman’s script and Demme’s direction are more interested in exploring the impact of that possibility on Melvin's life and the lives around him. It’s a story about hope, luck, disappointment, and the enduring search for something better, even when the odds are stacked against you. Robards, despite limited screen time (earning him a Best Supporting Actor nomination), leaves an indelible mark as Hughes – not as a caricature of eccentricity, but as a lonely, tired old man finding a moment of strange connection.

Melvin and Howard doesn't offer easy answers or neat resolutions. It presents life, messy and unpredictable, with affection and understanding. It reminds us that sometimes the most compelling stories aren't about grand events, but about the small moments, the chance encounters, and the everyday struggles and triumphs of people just trying to get by. It’s a film that lingers, not because of dramatic twists, but because of its quiet truthfulness.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's exceptional screenplay, the career-defining (and Oscar-winning) performance from Mary Steenburgen, Paul Le Mat's deeply likeable turn, Jason Robards' haunting cameo, and Jonathan Demme's assured, humanistic direction. It’s a masterclass in character study, capturing a specific time and place with warmth and authenticity. While its understated nature might have limited its initial reach, its quality endures, making it a standout title from the era – a true gem worth rediscovering on whatever format you can find it.

It leaves you pondering not just the mystery of the will, but the bigger questions about fate, fortune, and what truly constitutes a meaningful life – questions as relevant today as they were when this quirky, wonderful film first flickered onto screens.