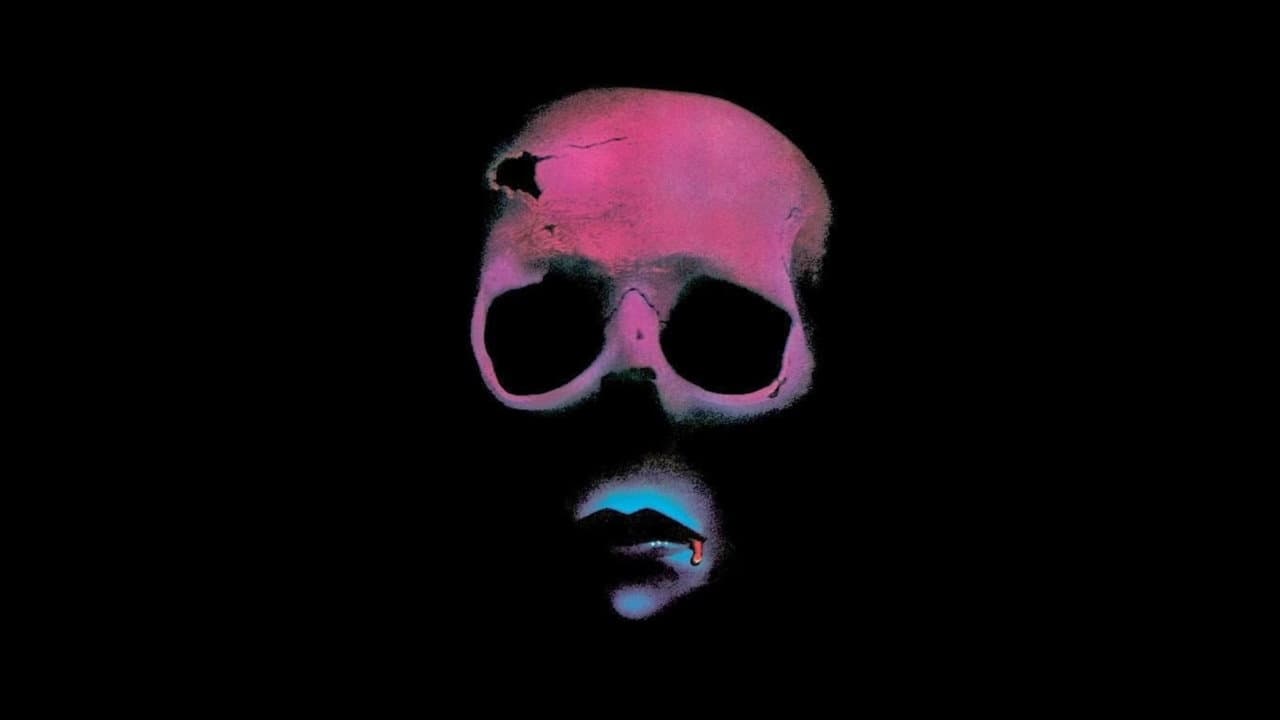

The flickering glow illuminates a drenched key, dropped deliberately into darkness. Then, a descent. Not into a cellar, but into a submerged world beneath a New York apartment building – a flooded ballroom, opulent decay shimmering beneath stagnant water, secrets held captive in the murk. Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980) doesn’t ease you in; it pulls you under immediately, immersing you in a suffocating beauty that borders on the baroque, a waking nightmare painted in lurid primary colours. If its celebrated predecessor, Suspiria (1977), was a brutalist fairytale, Inferno is its more elusive, perhaps more insidious sibling – the second chapter in Argento’s ambitious “Three Mothers” trilogy.

An Architecture of Unease

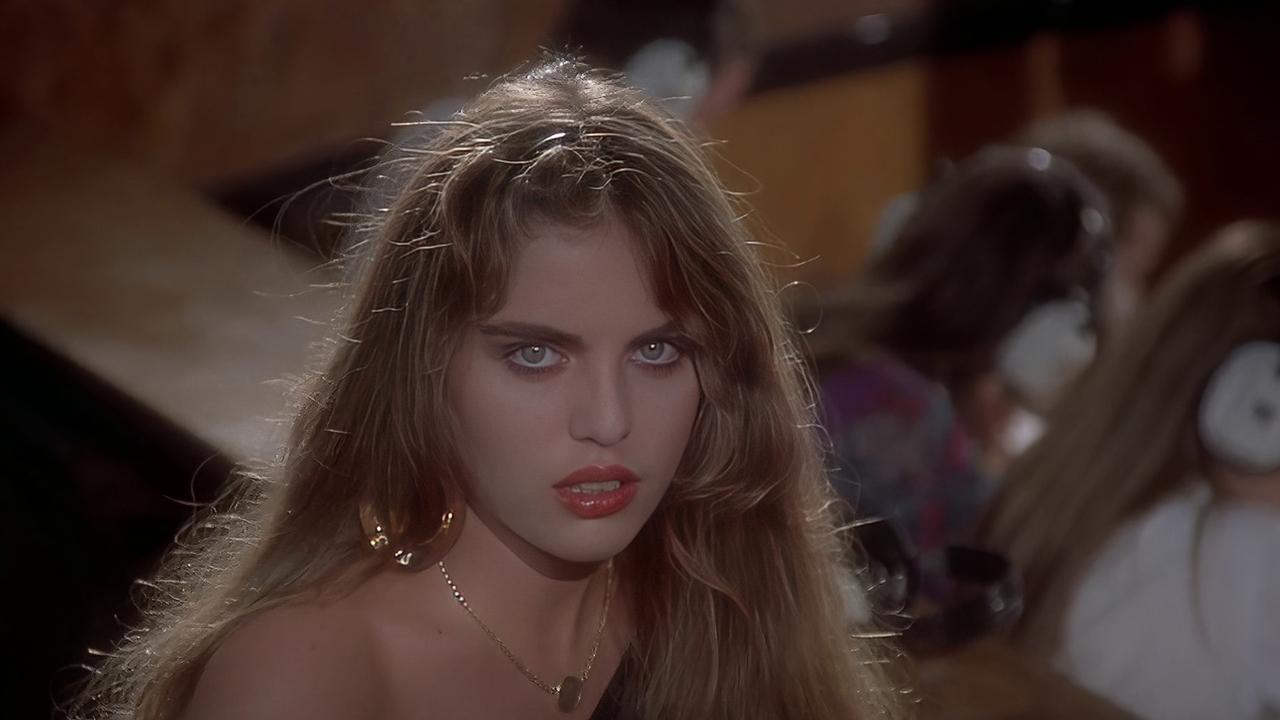

The premise, drawn loosely from Thomas De Quincey's Suspiria de Profundis, revolves around the arcane book "The Three Mothers," detailing three ancient, malevolent witches residing in key cities: Mater Suspiriorum in Freiburg, Mater Tenebrarum in New York, and Mater Lachrymarum in Rome. When poet Rose Elliot (Irene Miracle) discovers a copy in her imposing New York residence (a stunning piece of production design that feels both grand and claustrophobic), she suspects she lives in the domain of the Mother of Darkness. Her frantic letter to her brother Mark (Leigh McCloskey) in Rome sets events in motion, but Inferno isn't overly concerned with linear investigation. Instead, it drifts, focusing on atmosphere, texture, and exquisitely staged, often illogical, set pieces of death and discovery. Much of that imposing New York gothic architecture, incidentally, was pure cinema magic, meticulously constructed on soundstages in Rome, adding another layer to the film's pervasive sense of artifice and unreality.

A Symphony of Sight and Sound

Visually, Inferno is Argento operating near the peak of his stylistic powers. Cinematographer Romano Albani delivers visuals drenched in deep blues, blood reds, and sickly greens, compositions often favouring unsettling framing and architectural menace. The camera glides, stalks, and sometimes assumes the perspective of unseen forces, creating a palpable sense of voyeuristic dread. This visual assault is amplified by a score from Keith Emerson (keyboard wizard of Emerson, Lake & Palmer). Unlike the frantic, percussive rhythms Goblin brought to Suspiria, Emerson’s score is a bombastic, often operatic synthesizer opus, heavy on choral chants and thunderous chords ("Mater Tenebrarum"!). It’s polarizing – some find it overblown, others feel it perfectly matches the film’s excessive, dreamlike state. I distinctly remember the sheer volume of dread this score conjured through the tinny speakers of my old CRT TV; it felt less like music and more like the building itself groaning under supernatural weight.

Whispers of a Dying Master

One of the most fascinating "dark legends" surrounding Inferno's creation involves the uncredited, yet vital, contributions of another Italian horror maestro, Mario Bava. Argento, reportedly struggling with a severe bout of hepatitis during production, leaned on the ailing Bava (who sadly passed away the same year the film was released) for assistance. Bava's fingerprints are suspected on several key visual elements, including some optical effects, matte paintings, and most definitively, the design and execution of that unforgettable underwater ballroom sequence. It feels like a poignant, spectral collaboration – the final cinematic gasps of the director who gave us Black Sunday (1960) helping shape one of Argento's most visually ambitious nightmares. That underwater scene, with Rose navigating the submerged furniture and encountering a bloated corpse, remains a masterclass in surreal horror imagery, achieved through painstaking practical effort that still feels chillingly effective.

Fractured Narrative, Lingering Dread

Where Inferno often divides audiences, even Argento devotees, is its narrative structure, or lack thereof. Unlike Suspiria's relatively straightforward (for Argento) mystery, Inferno feels deliberately fragmented. Characters are introduced only to be dispatched violently, often without contributing significantly to Mark's quest. Leigh McCloskey's Mark is less a proactive hero than a bewildered witness swept along by arcane currents. Even Rose, the initial catalyst, disappears for large stretches. Some attribute this disjointed feel to Argento's illness during filming, suggesting it mirrored his own fevered state. Whether intentional or circumstantial, the effect is undeniably dreamlike and disorienting. You're never quite sure where the film is going, or whose eyes you'll be seeing through next. Does that sudden eclipse feel cosmically significant, or just another stylistic flourish? The film rarely offers easy answers, preferring to let the dread accumulate through its series of nightmarish vignettes.

The Cult Following of a Troubled Release

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given its challenging structure and intense violence, Inferno faced a difficult path to audiences, particularly in the United States. 20th Century Fox famously shelved the film for years after its completion, dumping it into limited release long after its Italian debut. This initial obscurity, contrasted with Suspiria's breakout success, ironically cemented Inferno's cult status. It became one of those legendary tapes whispered about in video stores, a film you had to seek out, its reputation growing through word-of-mouth among horror aficionados. Finding a decent quality VHS copy back in the day felt like uncovering a forbidden text itself. Its eventual (and much belated) conclusion arrived with Mother of Tears in 2007, finally completing the trilogy Argento envisioned decades earlier.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Inferno is not an easy film, nor is it as viscerally satisfying or narratively coherent as Suspiria. Its dream logic, fragmented plot, and sometimes overwhelming style can be alienating. However, judging it purely on narrative convention misses the point. This film is a sensory experience, a plunge into pure atmosphere and stunning, often grotesque, visual poetry. The production design is breathtaking, the colour palette intoxicating, and certain sequences (the underwater ballroom, the cat attack, the alchemist's fiery demise) are burned into the memory. Keith Emerson's score, while divisive, undeniably contributes to the film's unique, operatic intensity. The Mario Bava connection adds a layer of poignant history. For its sheer visual audacity, its power to evoke dreamlike dread, and its status as a cornerstone of Argento's surreal vision – flaws and all – Inferno remains a potent and essential piece of 80s Italian horror, a tape whose dark beauty continues to mesmerize long after the screen goes black. It's less a story told, more a nightmare experienced.